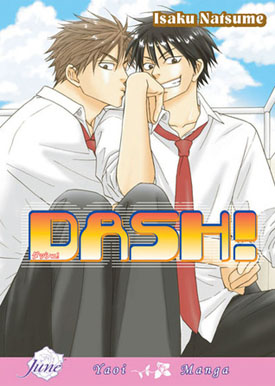

Isaku Natsume’s Dash represents an excellent example of the genre in shoujo manga (“manga for girls”) known in Japan as BL (boys’ love), bishonen-ai or shonen-ai, or, as is generally the case in the West, yaoi (pronounced, if one is being careful, “ya-oh-ee,” or more often probably “ya-oy”). It is, as the names may indicate, a genre about teenage boys falling in love, although directed mainly at teenage girls. These are quite often very romantic stories, sometimes highly melodramatic, usually with an element of humor that may or may not blend easily with the main narrative, and at their best provide a delightful look at youths on the verge of manhood learning to deal with their emotions.

Isaku Natsume’s Dash represents an excellent example of the genre in shoujo manga (“manga for girls”) known in Japan as BL (boys’ love), bishonen-ai or shonen-ai, or, as is generally the case in the West, yaoi (pronounced, if one is being careful, “ya-oh-ee,” or more often probably “ya-oy”). It is, as the names may indicate, a genre about teenage boys falling in love, although directed mainly at teenage girls. These are quite often very romantic stories, sometimes highly melodramatic, usually with an element of humor that may or may not blend easily with the main narrative, and at their best provide a delightful look at youths on the verge of manhood learning to deal with their emotions.

The main story in Dash! is about the relationship between Akimoto and Saitou. At the story’s beginning, Akimoto is a freshman member of the judo club who announces on his first day that he enrolled in that school because he admired Saitou, the school’s judo star. However, as Akimoto points out, Saitou “wasn’t all that good a guy.” He makes Akimoto his servant, running his errands, fetching lunch and drinks, and in general serving as his personal gofer. Akimoto puts up with it because that’s just the way things work. He is, however, somewhat frustrated: his hero attends club practice sessions only rarely, and when he does, he doesn’t spar or work out. Akimoto is quite vocal in his disapproval of Saitou’s attitude until he learns that Saitou was involved in an accident that severely injured the left side of his body: he’s only recently stopped dragging his foot when he walks, and still doesn’t have full use of his left arm and hand. When he realizes the frustrations that Saitou has been dealing with while maintaining his cocky attitude, admiration begins to turn into something else.

“Cheeky,” the “side story,” a common feature in yaoi collections, is about seventeen-year-old Yoshirou and his older cousin, Ohyama, known as “Taka-chan” to Yoshi. Taka-chan receives a phone call from Yoshi asking for refuge — he’s run away from home and needs a place to stay. The boys were very close when they were younger but haven’t seen each other for ten years; Yoshi, however, has not forgotten Taka-chan’s promise that he would always be on Yoshi’s side. Through a series of random and sometimes bizarre events, Ohyama begins to realize that Yoshi’s story was missing some details — most of them, in fact. Yoshi, however, does have a definite goal in mind, and it involves being an integral and intimate part of Taka-chan’s life.

In both stories, Natsume has built the narrative around characters who march to their own beats, and while I find Yoshirou and his situation barely credible, Saitou alone is worth the price of the book. Natsume has very deftly and subtly handled the revelation of a character who appears at first as a talented, cocky teenager on an ego trip, but who gradually allows his vulnerabilities to surface. And Akimoto turns out to be his match: he says at one point that grappling techniques are his specialty, and that it was beaten into him early on, “Once you grab hold, don’t let go.” It’s a delightful turn-around when Saitou, the immovable object, starts pursuing Akimoto, the irresistible force. The question of who is in control of the relationship at this point is an open one.

Natsume’s graphics dovetail with her characters and the narratives beautifully. They are very lean, almost spare, with the tendency common in shoujo manga of openness, a spacious quality I find very welcome. Pages seem to be designed rather than merely laid out, with odd-shaped frames, frames overlaid on images that bleed to the page edge, use of abstract elements, close-ups, and partial images, pattern and tone as spatial elements, and the Japanese sound effects, which have been left in, as purely visual accents (unless you read Japanese). And the characterizations are amazingly expressive. It’s a “cartoon-realism” kind of style, figures and especially faces reduced to the bare minimum necessary to carry meaning, and Natsume manages to pack a full range of expression into them. (This is not to imply that Natsume cannot make use of fully rendered figures, which she does in a couple of dream images — although even here, there is an admirable economy of means.) There is also no difficulty, as there is in some BL, in recognizing characters: each is completely individual, without resort to the kinds of “templates” that some mangaka seem to rely on, leaving us all too often trying to figure out who is who based solely on hair styles. Natsume’s graphic style also accommodates the seemingly requisite “comic” frames more easily than many, which is helped by the fact that she doesn’t resort to the “chibi” renderings that so often accentuate the comic relief.

And, considering that this is yaoi — which is often pronounced among American fans as “yowie!” — a word about the sex scenes: they are quite restrained, not in the least blatant. The emphasis is, after all, on the emotional context of the relationship between the boys. The book is rated for ages sixteen and over, although it might be appropriate for certain younger readers.

(Juné/Digital Manga Publishing and Oakla Shuppan, Inc., 2007 [orig Oakla Shuppan, Inc. (Japan), 2006])