Flesh and Bone is a prequel to The Surrogates, taking the story back fifteen years to the anti-surrogate riots of 2039.

Flesh and Bone is a prequel to The Surrogates, taking the story back fifteen years to the anti-surrogate riots of 2039.

The incident that sparks the crisis is the beating death of a derelict by three teenagers who are using their fathers’ surrogates without permission. Harv Greer is the patrolman on the beat who got the call to check out the scene. The derelict did get in a couple of good hits with a threaded pipe, which retained enough of one surrogates “cosmetics” (fake skin) to lead the police to one of the perpetrators — whose father happens to be rich and cagey enough to have his very high-powered attorney on hand when the police come knocking. Among the police is Greer, who has been drafted by the detective working on the case to get some “real life” experience under his belt. The Prophet starts agitating among his followers for a strong reaction to the death — the derelict was black and poor, the assailants white and well-off — and threatens to bring chaos to the city. There was one witness who heard the telling clue, one that points the finger not at the father, who is taking the rap because he knows he will get off, but at the son. There are also boardroom conflicts — VSI, Virtual Self, the company that manufactures the surrogates, was on the verge of introducing a juvenile line, but at the behest of the inventor of the surrogates, cancels the project — it would be really, really bad PR to go ahead at this point. And there is a payoff that results in a hit on the key witness.

No one comes across well in this one, except maybe Greer and the police. Venditti paints a dark picture of the criminal justice system and the ways those with money and power (which in America are synonymous) get their way. The Prophet, who is the conduit for the payoff money, uses the lawyer and the incident to advance his own agenda — his pious mouthings of God’s vengeance and the path of righteousness give every indication of being the manipulations of a successful politician, too much like many of our own contemporary “religious leaders.” (Although it would perhaps be more accurate to say that the Prophet may very well be sincere, but not blind to practicalities — he’s hardly an idealist.)

Venditti has a good eye for character and the way things work in the real world. Let’s face it, no one who follows the news with open eyes has any illusions about the prevalence of virtue in public life. Although the characters are somewhat one-sided (this is a comic, after all), they’re believable.

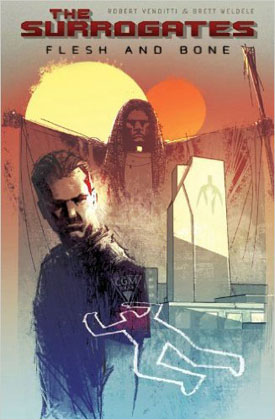

Weldele’s graphic work is, if anything, edgier than what he did for The Surrogates. It’s a matter of development: although the drawings retain the same rough quality, his use of color, modeling, and highlights shows a discernible degree of refinement. Visually, the book is compelling. It doesn’t hurt at all that it includes the same kinds of side material that showed up in The Surrogates: newspaper articles, a pamphlet from the Prophet’s church, an interview with the head of VSI. Let’s hear it for verisimilitude.

Everything I said about The Surrogates applies equally here: this is a refreshing departure for American graphic literature, showing nothing but strengths: the story’s a page-turner, the characterizations are apt and sharply rendered, and the graphic work is arresting. The few clichés that are here seem to be those that are an intrinsic part of the medium, and I certainly can’t argue with that. (Well, I could, but I won’t.) It’s a keeper.

(Top Shelf Productions, 2009)