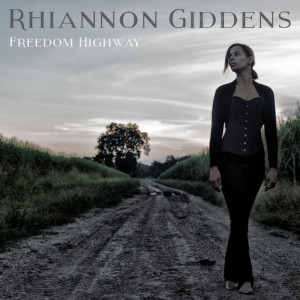

Rhiannon Giddens’ Freedom Highway is one of those rare recordings that grabs your attention right from the first note and won’t let go.

Rhiannon Giddens’ Freedom Highway is one of those rare recordings that grabs your attention right from the first note and won’t let go.

Giddens was one of the founders of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, a seminal folk group that brought the African-American stringband tradition to the attention of Americana fans both here and abroad. Freedom Highway is her second release since striking out on her own, and every song on it is as powerful musically and lyrically as Giddens’ opera-trained voice can make it.

Working with Louisiana-based musician, producer and cultural ambassador Dirk Powell, Giddens has curated and co-written a collection of songs that speak to America’s dark history of slavery, oppression and violence against the African people it brought to this continent against their will. More vibrant than any history book and as timely as tomorrow’s headlines and tweetstorms, this is music to rock your body and roil your soul.

Giddens is a songster, one who finds and collects songs and brings them to her audience. The few songs she has chosen to cover here are all illuminating and wrenching, drawn from the Jim Crow era and the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, and all are freshly relevant today in the era of Black Lives Matter. There’s “The Angels Laid Him Away” by Mississippi John Hurt, the briefly sketched blues ballad of a young black man who died violently. It’s sung to a sturdy folk tune that also forms the bones of other songs like “Railroad Bill,” here simply presented with Powell fingerpicking a resonator behind Giddens’ strong vocals.

And there’s another ballad, Richard Fariña’s “Birmingham Sunday,” the stirring tale of the deaths of four girls in the bombing of a church in that Alabama city. It’s a stately and very ’60s kind of folk song, most memorably recorded by Fariña’s sister-in-law Joan Baez, with it’s repeated refrain of “And the choirs kept singing of freedom.”

And most especially there’s the song that gives this album its title, “Freedom Highway” by Roebuck “Pops” Staples, written and performed by the Staple Singers to commemorate the 1963 March to Birmingham. This one’s in full-on gospel mode with a horn section in addition to a rock rhythm section and Cajun star Eric Adcock on two separate and very sanctified organs.

Giddens gets a vocal assist on “Freedom Highway” from Sri Lankan-American singer-songwriter Bhi Bhiman, who indeed has a wonderful voice and who contributes a song called “The Love We Almost Had” to the album, one of only two not specifically racially themed. The other is one of my favorites, the Cajun-via-New-Orleans two-step “Hey Bébé,” one of several that Giddens co-wrote with Powell. It’s a joyful, sexy love song, one that fits in perfectly and helps keep the album from being unremittingly somber.

And somber it is from the start, as the opening track “At The Purchaser’s Option” arrives in the defiant voice of a slave woman who knows nothing but labor and who realizes that someday her newborn baby will probably someday be sold to someone else and she’ll never see him again.

“Julie” has a real old-time sound from clawhammer banjo, fiddle and bowed bass, as befits the subject matter. It’s a chilling dialog between a female slave and her mistress-owner as the Union soldiers near the plantation. The owner begs Julie to tell the soldiers that the gold in her trunk belongs to her, Julie, but the soon-to-be-freed slave demurs: “Mistress, O Mistress, that trunk of gold / is what you got when my children you sold.”

Children and their loss is a theme that runs through the record, nowhere more affectingly than the soaring but tragic funk-rap “Better Get It Right The First Time.” It’s a modern tale of a young man who attends a party to which the police get called. Though played in a funky soul setting, in form it’s almost a field holler with a call-and-response making up the verses, the tragic story line emerging around the repeated phrase “Young man was a good man.” It’s a phrase all too common in today’s news.

Another ancient-sounding song written by Giddens is “Come Love Come,” the tale of a slave freed by the Union army, waiting for her man to join her across the lines in Tennessee. Its air of pensive sadness is accentuated by the arrangement, which consists of little more than Giddens’ deep, woodsy “minstrel” banjo, Powell’s electric slide guitar and swampy percussion.

To me the centerpiece of the record is “Baby Boy,” co-written by Giddens and her sister Lalenja Harrington, and powerfully delivered as a trio by those two with Leyla McCall, who plays cello and sings in the Chocolate Drops. The three voices weave a mythopoeic picture of a black male at three stages of his life, destined to lead his people to the promised land, seen through the eyes of the women who love him and watch over him.

Some people have the luxury of separating their art from their politics. But not Rhiannon Giddens and not the people she sings about. Giddens has translated hundreds of years of sorrow and pain into rootsy, earthy music that shuffles and moans, hollers and soars. Freedom Highway may be the first perfect album of the year. And it’s definitely one of the most important.

(Nonesuch, 2017)