The historical Vlad III, the Impaler, whose story this book purports to tell, was a voivode — “prince” — of Wallachia in the later fifteenth century. He is known mainly for his policy of independence from the Ottoman Empire, of which Wallachia was nominally a tributary state, and his favored means of punishment for his enemies, barbaric even for the time, from which comes his epithet. He was also known as Vlad Dracula (“son of the dragon”), a reference to his father, Vlad II Dracul, a member of the Order of the Dragon, a medieval chivalric order whose members were bound to protect the Cross and fight the enemies of Christendom. Vlad III was also inducted into the order at the age of five.

The historical Vlad III, the Impaler, whose story this book purports to tell, was a voivode — “prince” — of Wallachia in the later fifteenth century. He is known mainly for his policy of independence from the Ottoman Empire, of which Wallachia was nominally a tributary state, and his favored means of punishment for his enemies, barbaric even for the time, from which comes his epithet. He was also known as Vlad Dracula (“son of the dragon”), a reference to his father, Vlad II Dracul, a member of the Order of the Dragon, a medieval chivalric order whose members were bound to protect the Cross and fight the enemies of Christendom. Vlad III was also inducted into the order at the age of five.

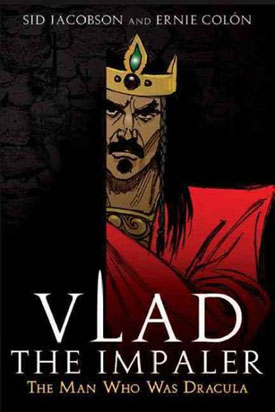

The graphic novel Vlad the Impaler, by Sid Jacobson with art by Ernie Colón, is an attempt to relate the story of Vlad’s amazingly short career as ruler of Wallachia — he only occupied the throne at intervals between 1456 and 1462. The early portion of the story relates Vlad’s sojourn with his brother Radu in Istanbul as a hostage. Vlad was not a cooperative young man, unlike Radu, and was regularly beaten, while Radu, who had caught the eye of the young Mustafa, son of the Sultan, was taken into the court. Vlad was sent back to Wallachia at the head of an army on the death of his father and older brother at the hands of the White Knight, and thus begins the seesaw of the rest of his life, as he loses and regains this throne, now in league with the Ottomans, now the Hungarians, leading ultimately to his death in battle.

The story also details his amorous adventures, a series of exploits almost as numerous as his various tortures and executions. He wasn’t a very nice man, at least in this telling.

I will hand Jacobson this — he does try to provide some basis for Vlad’s character being the result of his captivity by the Ottomans, and one can see how the repeated punishments, incarceration in a basement cell, and witnessing the Turks’ own barbaric tortures — including impalement — could color the development of Vlad’s character, but not in this telling. It’s all surface, it’s all very facile, and contains no depth at all. My question here was, “Why would Vlad want to imitate people he hated?” I can see an obvious answer, but didn’t find it here, which leaves a big hole in the rest of the story: what we’re left with is a stereotypical psychopath whose motivations are opaque to him and to us, and it all starts to look like nothing more than an excuse for lots of blood.

Ernie Colón’s drawing is very clean, clear and expressive, but I question whether he was the right artist for this book. The drawing does little to flesh out the story or the characters — it’s almost light-hearted in feel — and provides neither tension nor any real support for the narrative. It doesn’t even provide a believable setting for the gore, which has, in this rendering, no power to affect us one way or the other. While I’m not particularly squeamish, I am not what you’d call “hardened” in any way — I don’t like depictions of violence and bloodshed, although I’ll accept them if they make sense — but I found my self reading through and saying “So what?” I was not horrified, I was not titillated, I was just bored.

Perhaps I’ve just been spoiled, but to ask me to accept Vlad the Impaler as a legitimate work of graphic fiction is asking a lot. It doesn’t even really make it as an exercise in blood fantasies. The characters are cardboard, the action is trite, the graphic and narrative elements are a mismatch, and it’s all thrown into perspective by the appearance of the Count Dracula — or a caricature, at least — in the last two pages. This book has to be a put-on.

(Hudson Street Press, 2009)