About 30,000 years ago, the Martians fled their dying planet for Earth, where they took up a hidden residence, waiting for humanity to progess to the point where it could accept them. They send their Observers out into the world, to report back to their superiors in their hidden cities and to guide, surreptitiously, those who might make a difference. Some Observers conclude that there is no hope, and abdicate their responsibilities, becoming outcasts. One such, the Abdicator Namir, has concluded that the only hope for the Martians is the elimination of humanity. He means to bring it about however he can.

About 30,000 years ago, the Martians fled their dying planet for Earth, where they took up a hidden residence, waiting for humanity to progess to the point where it could accept them. They send their Observers out into the world, to report back to their superiors in their hidden cities and to guide, surreptitiously, those who might make a difference. Some Observers conclude that there is no hope, and abdicate their responsibilities, becoming outcasts. One such, the Abdicator Namir, has concluded that the only hope for the Martians is the elimination of humanity. He means to bring it about however he can.

It looks as though the time might be approaching. Human affairs are in their usual mess, and there is a boy, Angelo Pontevecchio, who has vast potential that can be tipped toward destruction or renewal. The Martians send Observer Elmis to stop Namir and protect the boy.

Edgar Pangborn was one of a small handful of science-fiction writers of the 1950s and early 60s who tackled the big questions at a time when the genre was still largely pulp. Like so many of his colleagues, he was a satirist — the genre seems to lend itself particularly well to social commentary — who approached his subject, the human condition, from many angles. A Mirror for Observers is a thoughtful book, quite different from the rollicking odyssey that is Davy, but still absorbing and giving the reader much cause for reflection.

It is not a fast-paced book. There are important events and moments of extreme narrative tension, but the mood is sober. Pangborn deals with a world in crisis, and once again that gift of prescience that so many of the greats in the field seemed to possess comes into play: the threat is a lunatic fringe with biological weapons that stand a good chance of wiping out not only the human race, but every mammal in the world. It is a measure of the maturity that Pangborn brought to his writing that there are no shining heroes with last-minute fixes, no technological breakthroughs, no marshalling of vast forces to defeat the bad guys. It is a small, intimate human story: the global tragedy is highlighted by the personal tragedy of Angelo, who now goes by the name of Abraham Brown, and his childhood sweetheart who, after he has been missing for nine years, has now become his love, whom we have also seen develop from a pert and precocious child into a sensitive and intelligent adult who happens to be on the path to a brilliant career as a concert pianist.

(It is, by the way, another mark of the subtlety of this book that, while we realize somewhat belatedly that the “future” Pangborn presents never happened (the book was first published in 1954; the events of the story take place in 1963 and 1972), it makes no difference. We’ve become used to that, at least those of us who remember the “Golden Age” of science fiction. In this case, far from dating the book, that fact becomes irrelevant: such is the degree of reality that Pangborn brought to his story.)

The stunning thing about this book, in retrospect, is that Pangborn doesn’t really comment on the central question: what is it that makes us human? He merely lays out the choices and leaves the reader to ponder. It’s not a particularly comforting book, in that regard, because he doesn’t really pull any punches, and while the ending can count as a “happy” one, it’s a qualified happy. We see two exceptional young people grow into magnificent adults in spite of every roadblock, learning love, compassion, and acceptance. It’s not a smooth journey, at all: we also see the cost. Lest I make it seem morbid, that is not at all the case. The one crystal clear answer to the question that Pangborn leaves us — or allows us to discover — is “hope.”

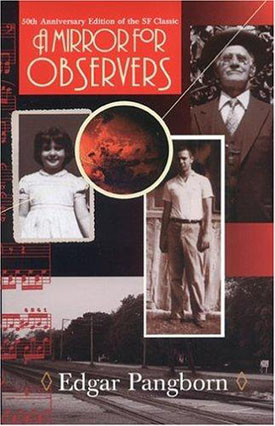

(Old Earth Books, 2004)