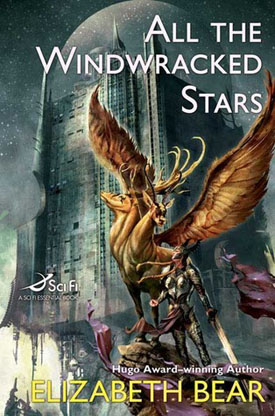

Take an event that we know from mythology, although it might have really happened. Let’s call it Ragnarok, just to give ourselves a point of reference, the final war when the Children of Light fought their brothers and sisters, the Tarnished Ones, and only three survived: the waelcyrge Muire, who lived because she ran; a wounded battle steed, the walraven Kasimir, who lived because the World Serpent granted Muire one last wish; and one other, the renegade einherjar Mingan, the Grey Wolf, who betrayed both sides and lived because he hid.

Take an event that we know from mythology, although it might have really happened. Let’s call it Ragnarok, just to give ourselves a point of reference, the final war when the Children of Light fought their brothers and sisters, the Tarnished Ones, and only three survived: the waelcyrge Muire, who lived because she ran; a wounded battle steed, the walraven Kasimir, who lived because the World Serpent granted Muire one last wish; and one other, the renegade einherjar Mingan, the Grey Wolf, who betrayed both sides and lived because he hid.

Cast the world two thousand years into its future. It’s a world in which sorcery and technology grew together, like two trees trained to twine around each other until their branches can’t be told apart. And now, the world is dying again as the coward and the traitor stalk each other through the world’s last city, a topsy-turvey mix of trumans, halfmans, unmans, nearmans, mutants, moreaux (the animal-people), sealed arcology, open streets, congestion, emptiness, slums that never see daylight, decaying walls, desperation and despair. And they start finding their dead siblings, reborn in the people of this future — Kasimir’s rider, Herfjotur, now the moreau Selene, a cat transformed by the Technomancer Thjierry Thorvaldsdottir, a captain in the Technomancer’s elite guard; the dead Strifbjorn, whom they both loved, has come back as Cathoair, a young show-fighter and whore; Yrenbend, whom Muire finds in the rat mage moreau Cristokos. All unknowing of who they are, or were — they are and are not reborn. And finally, although it perhaps took longer than it should have, Muire discovers why this world is dying. The Grey Wolf knew all along.

As I sit here, having just finished this book, I find myself wondering why stories like this one — painful stories that don’t quite settle into despair — move us so deeply while happy stories of shining heroes and golden quests, though they might lighten our mood for a moment, seldom resonate to the depth that this one does. Bear’s not making a pitch for despair as our normal state: redemption hovers in the background for a long time before it makes its entrance, even if it serves only to introduce resurrection.

I’ve been reading Joseph Campbell again, and bring this insight to this discussion: life is a series of resurrections, until we reach the final transformation that leads to a rebirth we hope for but can only guess at. And Bear rubs our noses in the fact that neither redemption nor resurrection are all they’re cracked up to be, but they do mean you get another chance. Call it a study in the cyclic nature of entropy.

It’s also a love story, and in Bear’s hands that has become nothing so shallow as romance. The love is on the same deep, painful level, a multifaceted thing of protection, sacrifice, obsession, and finally the realization that love must allow the resurrection, but in so doing, it must also allow the death that is necessary. It’s become almost an identifying mark of Bear’s work that she cuts to the core of what loving means, what it costs, and lays bare all the ways we use that very imprecise but necessary word.

Elizabeth Bear has started to scare me. All the Windwracked Stars packs a terrific wallop, and any artist who can achieve that level with any consistency is frightening indeed. There’s a degree of honesty that any artist has to achieve if they want us to pay attention beyond the moment: they can’t be afraid of the hard places. Bear’s there.

(Tor Books, 2008)