This formidable anthology is subtitled The Best Crime Stories From The Pulps During Their Golden Age — The ’20s, ’30’s And ’40s. With a couple of exceptions, that is a fairly accurate description.

This formidable anthology is subtitled The Best Crime Stories From The Pulps During Their Golden Age — The ’20s, ’30’s And ’40s. With a couple of exceptions, that is a fairly accurate description.

At its best, pulp fiction works like a tin clockwork toy, reliably and efficiently providing action, plots with twists and snappy endings. Its heroes are rarely memorable and its themes seldom profound, but every so often there are great exceptions to the rule, and generally it is written in a spare and economic style that suits its material perfectly. Editor Otto Penzler has clearly put in a lot of work selecting stories that show the wide range of variation in quality, style and substance.

A few have not aged well. One or two are disfigured with racist clichés, some of which are so outdated they would require explanatory footnotes to offend the modern ear. Why, for example, would a person of Greek descent be referred to as a “ginny?” Your correspondent has encountered a reasonable amount of old-fashioned trash talking over the years, but that one baffled her. Moreover the women in these stories are pretty much uniformly little plastic beauties. The good ones are adorably perky, brave and devoted to their men. The bad ones are described with a lot of cat imagery and use their evil gorgeousness to confuse and enthrall males.

All this was the literary convention of the day, of course, and so your correspondent overcame her deep-seated feminist rage, et cetera, et cetera, and enjoyed the damn book anyhow.

For it does entertain, no question. Fists fly, guns spit flame in dark rooms, cars pursue other cars on winding mountain roads, mysteries are presented and solved. All the brassy cynicism of the Depression years balances the quaintly imagined romantic life of gangsters.

There are surprises, good and bad. An entire previously unpublished story by Dashiell Hammett, still in the original manila envelope in which it was mailed from his apartment in San Francisco way back when! It’s a Steinbeckian little piece titled “Faith,” technically not a pulp crime story but great to find here. Other short fiction by Hammett, Chandler, Woolrich and Cain stand out among the pieces by lesser talents, reminding you sharply of just how good the genre could be.

It’s easy to grumble about Leslie White’s “The City of Hell!,” a wildly improbable fascist-cop fantasy, but at least the prose is lean and passionate. On the other hand, here is Leslie Charteris, clearly being paid by the word in “The Invisible Millionaire.” After 35 pages of coy overdescription and endless adoring references to the Saint’s perfect features, your correspondent was ready to go out and bitch-slap Roger Moore. And was it really necessary to include an entire badly-written novel (“The Crimes of Richmond City”) by Frederick Nebel? He may have been one of the seminal pulp writers, but surely a short story from him would have satisfied honor.

Some are so crazy-bad they’re delightful. Here’s Frederick C. Davis’ “The Sinister Sphere,” featuring a hero who runs around with his head in a glass ball. In Carlos Martinez’s “The Devil’s Bookkeeper,” a bouquet of roses conceals a deadly accountant bent on revenge, and only the heroine’s forethought in wearing chainmail under her gilded dance costume saves her from flying bullets. And who couldn’t love Perry Paul’s “The Jane from Hell’s Kitchen,” a wronged gun moll with a purple paradise of a secret lair, who goes after her crimelord ex-boyfriend (“The Ghost”) with a biplane, and shoots him out of the sky? No, they don’t write ’em like that anymore.

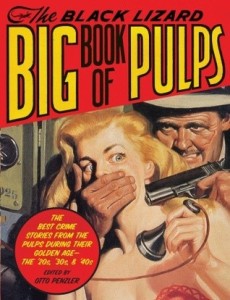

All in all it’s a swell collection, a fine overview of the genre. The cover is wonderfully lurid, and the interior graphics perfectly imitate the rough charcoal illustrations found in pulp digests. There is a brief piece by Harlan Ellison discussing his arrest record. There are scholarly and biographical notes for each entry. If you’re in a mood to open a bottle of cheap rye and put your feet up on your desk as you wait for a client to walk into your outer office, this collection will take you there.

Nine black masks out of ten.

(Vintage Books, 2007)