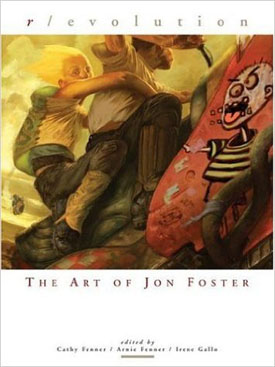

One thing that I’ve found a delight while reviewing for GMR is the chance to move into fields I’ve never been able to focus on much before, one of which is illustration, specifically the art of the fantastic. Given my love of science fiction and fantasy and their allied genres and my background in fine art, it’s a wonder to me that I’ve never concentrated on this, and so have missed artists such as Jon Foster — until now.

One thing that I’ve found a delight while reviewing for GMR is the chance to move into fields I’ve never been able to focus on much before, one of which is illustration, specifically the art of the fantastic. Given my love of science fiction and fantasy and their allied genres and my background in fine art, it’s a wonder to me that I’ve never concentrated on this, and so have missed artists such as Jon Foster — until now.

Beginning with a biographical sketch by Cathy Fenner that relies heavily on statements by Foster (one of the best ways to get inside an artist’s head), the book is largely composed of illustrations of examples of his work, tracing its development from project to project, with historical/contextual commentaries and laudatory comments by other artists One thing that is evident early on is his fascination with robots, and not only the mechanical aspects: they become human in many small but significant ways, personalities in their own right. The humans in Foster’s paintings and drawings are, equally, unique and individual. These are not just pictures — they are characterizations. Foster also manages to get a real sense of motion into his work — these are, many of them, action-pictures, and the “action” part is there so definitely that one’s reaction is visceral.

Foster also displays an amazing range, from the completely fantastic vision of works such as “Mistborn” and the awkwardly mechanical early robots to his series of concept and storyboard drawings for Dear Anne: The Gift of Hope, a film about Anne Frank. Among my favorites are his covers for the Star Wars books and his illustrations for Neil Gaiman’s Hunter series. There is a sense of conceptual freedom here that I find refreshing after years of buying books in spite of their covers — I don’t think he could turn out a “standard” illustration if he tried.

The eye-opener for me, relishing as I did the painterly qualities of Foster’s renderings, was discovering that he works largely on the computer, often beginning with a hand-drawn sketch or an oil painting and then working it through various versions digitally. (I think I hate him — Photoshop and I are uneasy accomplices, at best.) The ability to turn out finished work that still retains the sense of the artist’s hand while working with a computer is impressive.

A grumble: none of the illustrations are dated, and one must rely on the text to get a sense of when things happened. This is not an insuperable problem, since the book seems to be laid out chronologically, but (if anyone is listening), it would be nice to have that information available right there with the other data.

On the whole, this is a handsome tribute to one of the most interesting illustrators working today. While I normally favor more substantial texts in art books, I suppose it’s a little early for scholarly studies of Foster’s work. In the meantime, this will do very nicely.

(Underwood Books, 2006)