Everybody knows one Steve Goodman song. The Chicago-born and -bred folksinger wrote “City of New Orleans,” the iconic ’70s song popularized by Arlo Guthrie. If that were the only thing he’d ever done, it would be enough, because it’s a great song, expressing universal truths in a tale set in a particular time and place. Its chorus of “Good morning, America, how are you? / Don’t you know me, I’m your native son,” perfectly captured the blend of confusion and optimism that reigned over the late 1960s and early 1970s in America, as a generation came of age that loved their country but felt alienated from some of its actions and beliefs.

Everybody knows one Steve Goodman song. The Chicago-born and -bred folksinger wrote “City of New Orleans,” the iconic ’70s song popularized by Arlo Guthrie. If that were the only thing he’d ever done, it would be enough, because it’s a great song, expressing universal truths in a tale set in a particular time and place. Its chorus of “Good morning, America, how are you? / Don’t you know me, I’m your native son,” perfectly captured the blend of confusion and optimism that reigned over the late 1960s and early 1970s in America, as a generation came of age that loved their country but felt alienated from some of its actions and beliefs.

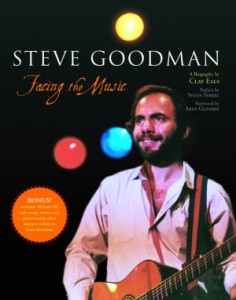

Seattle journalist and writer Clay Eals has attained a lifelong ambition to honor Goodman with this towering biography. At almost 800 pages, it’s almost as big as its subject was in real life. Goodman, who stood all of 5-foot-2, died at the age of 36 in 1984, after battling leukemia for 17 years.

(Disclaimer: I am slightly acquainted with the author. In the mid-1970s, he and I both worked on the Oregon Daily Emerald, the independent student newspaper at the University of Oregon.)

Eals conducted more than 1,000 interviews in the course of preparing to write this book, and did an impressive amount of other research. Among those interviewed were, of course, Arlo Guthrie, who recorded the most famous version of “City of New Orleans,” Bonnie Raitt, Gordon Lightfoot, and Hillary Rodham Clinton, who attended high school with Goodman. He also interviewed scores of other people who never became famous, who knew Goodman in school, synagogue and neighborhood.

Goodman was born and grew up in and around Chicago, the son of a car salesman and a homemaker. Diminutive, outgoing and fun-loving, he excelled at music from the start, and was singing solo in his synogogue from an early age. He followed a path into music similar to one tracked by many in his generation, picking up the guitar to learn the popular songs of the day. Always a top student in high school, by the time he entered college his interest in music was interfering with his studies such that he dropped out. Then his leukemia diagnosis, which at the time was nearly always quickly fatal, spurred him to focus on the thing he most loved in what he believed would be a short time left to him. He played in Chicagoland clubs and even took a stab at the New York folk scene, in between bouts of rigorous chemotherapy treatments in a New York hospital.

He had first started writing what would become “City of New Orleans” one day in 1967 when he skipped classes at the University of Illinois to ride the eponymous train to New Orleans and back. He completed it after a 1970 trip on the same train with his fiancee, Nancy Pruter, out of the Illinois Central Station to a town about three hours south to visit her relatives. The song’s first two verses practically wrote themselves as he looked out the window, Nancy snoozing beside him, jotting down notes on what he saw. A few months later, a guitarist acquaintance named Richard Wedler suggested that Goodman add a third verse, describing what he saw inside the train’s cars — mothers with sleeping children and old men playing gin rummy.

We’re not quite at page 200 when we hit this point in Goodman’s life and career. The rest of the book is a detailed account of his musical career, gathering lots of fans but always just on the outside of the big leagues, always with the poignant realization that his time is limited.

Eals obviously is a serious fan, but he also has a keen appreciation of music and a working journalist’s way with words. He has thought long and hard about his subject matter, and talked to a lot of people about it, and has come up with some worthwhile insights. A good example is this paragraph about “City of New Orleans”:

What Steve may not have realized was how effectively “City of New Orleans” could tap the impending nostalgia craze fueled by the younger generation and soon to be validated by a Life magazine cover. The song was a way to embrace something old without swallowing the excesses of an older generation that seemed bent on destroying, with plasticized progress, the charming, venerable icons of the romantic past.

It’s hard to complain about an excess of research and detail, but one gets the feeling that the book could have been a bit more manageable if Eals weren’t quite so obsessive. For example, did we really need to know the name of the motel where the Miami-based duo Bittersweet were staying in Southfield, Mich., when they took Steve there to jam after he opened for them at a local club? And a less thorough writer might have started the book with the scene in 1967 when the germ of the song was planted, then filled in the backstory of his life to that point in a brief chapter, and cut to the up-and-coming folk singer’s career.

Where the author’s attention to detail, journalist’s experience and storyteller’s ear come to the fore is as the story picks up steam. In 1971, Kris Kristofferson, who was just on the cusp of major music stardom, “discovered” Goodman singing at a club in Chicago and was impressed. Also playing in town at the same time was superstar Paul Anka. The story of how Goodman ended up playing for both of them, and turning them on to his friend John Prine, is red meat to anyone who loves to read about music and musicians. As is the tale of the heartbreaking way Prine, whom Goodman had to practically drag to New York, ended up getting a record deal instead of Goodman. Still, within a few months, Goodman was signed to Buddah (sic), and enlisted Kristofferson and Norbert Putnam, fresh off of producing Joan Baez’s Blessed Are…, to produce Steve’s debut.

And of course, there’s the details of how Guthrie came to hear and finally record “City of New Orleans,” and lots more. Lots and lots more. By the time he’s a full-fledged recording star and headed for his early demise, we find that we care about him more because we know him so well, not just as a singer but as a son, brother and friend to the many people who knew him.

In other words, as an inveterate reader of music lore, I loved the book, even though I sometimes wished for the Reader’s Digest version. Kudos on the book’s design, which among other things puts photos, drop quotes and footnotes in a column on the outer third of each page. You can order it from Eals’ website.

(ECW, 2007)