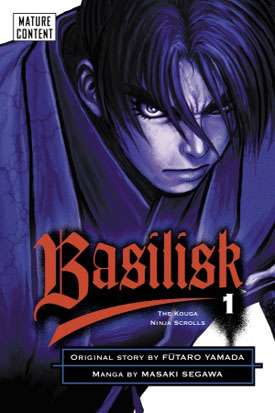

Basilisk is Masaki Segawa’s manga adaptation of Futaro Yamada’s 1958 historical novel The Kouga Ninja Scrolls. It counts mostly as “historical fantasy,” and as rendered in the manga version, the story line is fairly spare while the “surround,” the visual component, is very rich. As is generally the case, the manga has given rise to a TV anime series, also available on DVD, and even a live-action film.

Basilisk is Masaki Segawa’s manga adaptation of Futaro Yamada’s 1958 historical novel The Kouga Ninja Scrolls. It counts mostly as “historical fantasy,” and as rendered in the manga version, the story line is fairly spare while the “surround,” the visual component, is very rich. As is generally the case, the manga has given rise to a TV anime series, also available on DVD, and even a live-action film.

This is a period piece, taking place about 1614. The Shogun, Ieyasu Tokugawa, has decided that two ninja clans, the Iga and the Kouga, will between them decide who his successor will be as Shogun. The Kouga are to represent his youngest grandson, Kunichyo, while the Iga represent his oldest, Takechiyo, in a battle to the death. Each side will be comprised of ten ninja: the clan of the survivor will determine the succession. The fight begins immediately: Ieyasu has called the leaders of the two clans, Ogen Iga and Danjou Kouga, along with a ninja each to represent their clans in a demonstration at which the arrangement is announced and the truce that has kept the two clans from decimating each other is nullified. Ogen and Danjou immediately kill each other, and the Kouga copy of the scroll announcing the contest and the participants is stolen and destroyed by the Iga.

The wrinkle is that the two heirs to leadership of the clans, Oboro of the Iga and Gennosuke Kouga, have fallen in love and are betrothed. Oboru is not a ninja, although she possesses magical vision that can nullify any ninja technique, while Gennosuke also has magical vision that can turn any attack back on its perpetrator. The story works its way through the roster of opposing ninja, and we are treated to some amazing techniques and some spectacular deaths, until, as expected, only Oboru and Gennosuke are left.

This is, by the way, definitely “adult” manga: aside from the graphic violence, there is a fair amount of nudity and several sexual situations, and the series is recommended for readers eighteen and older.

Being a particularly visually oriented specimen of a visually oriented species, I was quite taken with the graphics. The style is a sophisticated variation on “Disney realism” as shown by Disney Studios at their height — the adept use of shading and line weight adds a particular richness to the visual component, and the comics quality is both contrasted and heightened by the occasional use of backgrounds that appear to be photographic. (One interesting anomaly: the clips I’ve seen of the anime version are much less Disney-like than the graphics in the manga, although the anime itself is a far cry from Saturday morning cartoons.) One thing I have noticed in general about the manga I’ve been reading lately is the strong influence of Western art and even more so, the visual conventions of Western comics. I would have expected, with Japan’s rich tradition of graphic art, particularly in the genre of woodcuts, more continuity with that tradition, but aside from an occasional frame that dispenses with Western ideas of perspective, or a few of the “wide-angle” shots on the road that recall Hiroshige, that seems to be almost lacking.

However (there’s always a however), one thing notable about Basilisk is the very Japanese use of grotesques in characterization. Some of the characters remind me of eighteenth- or nineteenth-century Japanese comic watercolors in their use of exaggerated body types and distorted features. The ninja Shougen Kazamaki, for example, resembles nothing so much as a human-spider hybrid, in keeping with his ninja technique, which makes use of sticky saliva and the ability to scurry up walls and trees with no problem. For that matter, the rendering of the Shogun himself does recall Japanese images much more than Western. On the other side of the equation, the less specialized characters are uniformly attractive — even gorgeous (and again, it’s that Disney idea of beauty for both male and female characters) — but one looks in vain for what one has come to expect as a Japanese ideal until the appearance of the Lady Okufu, godmother to Takechiyo, in volume 4. She is almost straight out of Utamaro, and the remarkable thing is that there is no conceptual gap between her and the other characters: she fits right in visually even though her aesthetic antecedents obviously have nothing to do with Western traditions.

The story, depressing as it is (although one wonders if in the hands of someone like Akira Kurosawa it might have taken on a tragic inevitability of olympian proportions), is absorbing, and far from becoming merely a litany of horrors, it pushes the limits of what might seem to be its obvious constraints: we know who will meet in the final battle, but we have no inkling of what the outcome might be. It is surprisingly powerful, and an indicator of Segawa’s ability as an illustrator that there is such a deep sense of silence coming off the last few pages.

(Del Rey Books, 2006-2007 [orig. Kodansha, Ltd. (Japan), 2003])