Joseph Thompson penned this review.

Joseph Thompson penned this review.

There’s nothing worse than travelling with a dreamer on a mission to recapture his or her youth. The old fishing holes are puddles, quaint villages become banal suburbs, and magical forests shrink to mundane thickets. The fantastic is a dynamic experience. Our memories are static postcards — nostalgia at its best.

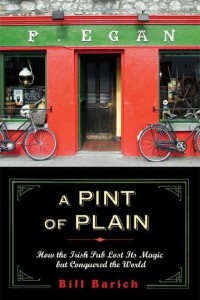

When I first picked up Bill Barich’s A Pint of Plain: Tradition, Change, and the Fate of the Irish Pub, my initial response was “Aw hell, time for a trip down memory lane.” As a reader, a writer, and a critic, I owe an apology to Barich: A Pint of Plain is not what I assumed it to be. It is not a midlife crisis-fueled memoir trying to cram reality into some cotton candy recollection. It is not a treatise for some nonexistent “good ol’ days.” I stand corrected and humbled.

A Pint of Plain is a brilliant hybrid of new journalism and memoir. Building off the experiential style pioneered by Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, and Truman Capote, Barich explores the origins and present state of the Irish-themed pub phenomena. He brings the reader into the pubs of his youth and then exposes them for the fantasy that they are. Barich balances thoroughly researched fact with personal experience and vignettes about the personalities he met on his journey. With each pint he knocks back, the reader is there at the table with him.

Throughout the book Barich balances the magic of dreamer with the self-awareness of a great storyteller. He uses this magic to create the ideal pub without falling prey to his own illusions. This saves him from the trap of nostalgia. He uses the clichéd image of the Irish pub with its fiddlers and a name suffixed with “and Sons” to start his journey, and then dissects it with the precision of a biology professor.

The dissection is not pretty. Barich’s research — both liquid and academic — is dense. He uses it to expose each piece of paraphernalia on the wall and every imported brogue as carefully chosen elements by executives at Diageo-Guinness USA, a division of Guinness Limited. He explodes erroneous myths of Ireland’s relationship with drinking and details the current state of beer. In a less skilled hand, the truth would sound cynical, as if Irish-themed pubs were the dastardly creation of accountants and business executives.

In fact, they are. But Barich transcends this initial reaction to discover the push behind the phenomena. He uses his experience — his disappointments with reality as well as an appreciation of well trained publicans — to move beyond pointless corporate criticisms and naïve fantasies and to write about a realistic understanding of what the Irish pub means in Ireland and around the world. Or, as he finishes chapter three:

Your only choice was to put one foot in front of the other and stride toward a largely positive vision of the future, although you risked leaving the lessons of the past behind.

In the new Ireland of Range Rovers, security alarms, and pistachio oil, was there still room for a quiet place apart devoted solely to talk and drink? That was a question worth investigating.

By his own admission, Bill Barich is a dreamer on a mission to recapture his youth. But he greets each illusionary fishing hole, village, and forest with clarity and wisdom. In the end, the reader — not the author — feels nostalgic and thirsty for something never really existed.

(Walker and Company, 2009)