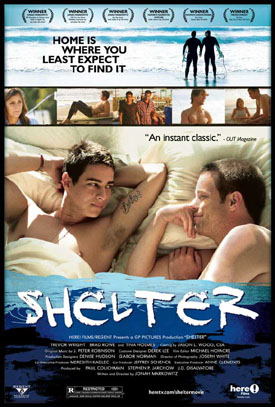

The problem with being a reviewer is that one automatically begins deconstructing the experience of any art, whether it be in a museum or in a hall of popular culture, which is not always the best way to deal with something, particularly if you’re dead set on taking a night off. At any rate, once upon a time I hauled my reclusive self out to a movie house to see Shelter, a feature from Jonah Markowitz that garnered very positive press at Chicago’s Reeling gay and lesbian film festival in 2007. Mostly I went because I was in the mood for a nice, uncomplicated “boy meets boy” story.

The problem with being a reviewer is that one automatically begins deconstructing the experience of any art, whether it be in a museum or in a hall of popular culture, which is not always the best way to deal with something, particularly if you’re dead set on taking a night off. At any rate, once upon a time I hauled my reclusive self out to a movie house to see Shelter, a feature from Jonah Markowitz that garnered very positive press at Chicago’s Reeling gay and lesbian film festival in 2007. Mostly I went because I was in the mood for a nice, uncomplicated “boy meets boy” story.

Just so you know, I did enjoy the film thoroughly, although on leaving the theater I had reservations. On reflection (read “deconstruction”), I find my reservations evaporating. So maybe that is a good thing after all.

Before I get to the film itself, one observation: I don’t think this movie would have been made five years before it was. It could have been, but it wouldn’t have been – we are without doubt in a post Brokeback world. The reason I say this is because the film is virtually free of stereotypes. More on that later.

Zach (Trevor Wright) is a young man who had dreams of going to Cal Arts, but gave it up because his family needed him. Instead, he makes do with practicing “street art” and taking care of his young nephew, Cody, while his sister Jeanne (Tina Holmes) works her way through a series of boyfriends. Best friend Gabe (Ross Thomas) is off for an extended trip, and while he is away his older brother Shaun (Brad Rowe) comes to town from LA to break a case of writer’s block. Shaun taught Zach to surf, Zach’s other release from family duties, and they spend time on the waves until one night, as they are hanging out at Shaun’s (and Gabe’s) house drinking beer, comes the fateful kiss. Zach’s feelings are, to say the least, mixed: he realizes that his feelings for Shaun are genuine and deep, but as might be imagined, the fear arising from the reactions he expects from his family – his sister, particularly, reveals herself to be somewhat homophobic – and his friends, particularly his on-again-off-again girlfriend, Tori (Katie Walder), provide enough conflict to keep him busy.

Back to the stereotypes: there aren’t any. This is the second “gay” movie in my experience to be stereotype free, and I think on that score alone it merits attention. There’s not a limp wrist in the entire thing, nor are there any raving homophobic rants. Even Gabe’s reaction, with questions like “Did you always know?” “Do you think he’s hot?” about a man passing by on the street, is just Gabe’s personality – he’s just a clumsy, half-formed guy whose social skills, even with his best friend, are rudimentary. Jeanne’s near-hysterical insistence that Zach keep Cody away from Shaun (Cody adores Shaun) is revealed to stem from ignorance and a sincere concern for her child, although she’s seemingly not the best mother the world has seen.

Which leads me to the film’s real strength, which is in the characters and their portrayals. I have to admit that leaving the theater I was of two minds about the accolades for the cast. The more I think about this film, however, the more I realize the subtlety and depth the actors have brought to it. Wright’s portrayal of a young man faced with something in himself that scares the hell out of him, his anger and fear, is touching and beautiful. I’m still finding in memory small bits of scenes, tiny little reactions that flesh out Zach’s character and make him even more believable than my first impression. Rowe, as the gay man who knows he’s gay and knows he is not in a place where he can be really open about it, plays it honestly and directly as a man who’s fallen in love, quite unexpectedly, and who has the patience and savvy to understand that he’s dealing with someone who is terribly vulnerable and confused. (And I can’t stress enough that the character Rowe gives us is not a “gay man,” but simply a man. This is as much a political decision as anything else, but it also reflects accurately what most gay men are.)

Markowitz has done some interesting things with vignettes stacked up in series to mark the passage of time – brief scenes of Zach and Shaun roughhousing on the beach, making out, spending time playing with Cory as their relationship develops – and I’m not sure it it works as well as it might. Part of it might be that the film is set in southern California, the land of no seasons, so there’s not really a strong sense of the passage of time. Zach’s family is struggling and they don’t live in the best part of town, a fact brought home in the industrial view from his studio on the roof of his house and, in fact, in the subjects and form of his drawings. The contrast with Gabe and Shaun’s comfortable circumstances underlines, among other things, the shape of Zach’s difficulties in dealing with his situation as well as the promise of freeing himself to take what he really wants and needs. The film is full of touches like this, and it makes a rich experience.

It’s unfortunate that the film was scheduled for severely limited theatrical release – it’s the kind of movie that would give right-wing anti-gay activists cardiac arrest, and the inevitable calls for a boycott would undoubtedly have boosted the box office. The role of “family” in this film is ambivalent – in spite of his feelings for his family, it is not the most constructive force in Zach’s life, and (I’ll permit myself one small spoiler here) the implicit assumption that he and Shaun will form the nucleus of a family themselves is unavoidable, given how it all shakes out at the end.

Bottom line: It’s a challenging film in ways that point up the strength of film as a medium, beautifully conceived and almost flawlessly executed. It was, ultimately, released on DVD. If you have a chance, see it.

(Here! Films, 2008)