Craig Clarke penned this review.

Craig Clarke penned this review.

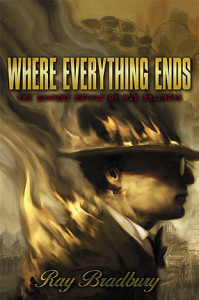

The subtitle “The Mystery Novels of Ray Bradbury” quickly tells us what’s between the covers of Where Everything Ends, a collection of an underappreciated portion of the author’s bibliography: three crime novels written between 1985 and 2003 that feature an unnamed narrator/protagonist (very much Bradbury’s doppelganger) and detective Elmo Crumley dealing with mysteries during the Golden Age of Hollywood.

Published for the first time here, the title story is the short story that came first and inspired the rest. If read after the novels (it is placed at the back), it comes across as definitely a lesser work: one written by an author still trying to get his bearings in the genre. And he makes the beginner’s mistake of focusing too much on how the crime was done instead of on his own forte, character. Luckily, Bradbury eventually combined the two and produced three novels that equal his speculative output in skill and heart, if not necessarily excitement.

In 1985, over twenty years since the publication of his last full-length work, 1962’s Something Wicked This Way Comes, Ray Bradbury reentered the novel-writing world with the release of Death is a Lonely Business, his first foray into a genre epitomized by Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and Ross Macdonald — namely the crime investigation novel.

The narrator of Death is a Lonely Business is a writer living in Venice, California, where the local carnival pier is being demolished. He discovers the body of Willie Smith, underwater and trapped in a disused lion cage. Then a strange shadowy figure begins appearing in hallways and outside windows at night, and the number of murders increases. The narrator teams with local police detective Elmo Crumley — reluctantly, at first, on Crumley’s part — to solve the case. The only clues they have are the writer’s intuition, articles that go missing from the deceased’s residences, and a blind man’s keen sense of smell.

This book has many layers to it. First, on the surface, it’s a fine noir pastiche. Second, our hero is especially interesting as a portrait of Bradbury himself in 1949. The naive, plump, 27-year-old writer, who is just becoming successful, inspires immediate identification from fans of the master’s work. We already like the author, so we immediately root for his doppelganger. I especially enjoyed the personal clues Bradbury laid within the story, some of which take a brave person to lay bare in print. But they work to gain our sympathy, which is quite necessary; in the beginning the writer is painted — whether deliberately or not — as a somewhat unsympathetic character prone to outbursts.

The other characters are just as fascinating: Crumley, the cop who just happens to also be a writer; Fannie, the 380-pound sedentary soprano; A.L. Shrank, the psychiatrist with the downbeat library; Cal, the incompetent barber with the ragtime past; John Wilkes Hopworth, the ex-silent film star who still pines for former love Constance Rattigan, his former costar who is dead set on not becoming Norma Desmond from Sunset Boulevard (“That dimwit Norma wants a new career; all I want most days is to hole up and not come out”); and Henry, the blind man, who is the only one who can identify the killer — by his smell.

Five years later Bradbury revisited the genre with 1990’s A Graveyard for Lunatics, subtitled “Another Tale of Two Cities.” It is now 1954, and the Bradbury character is working for Maximus Films as a screenwriter. The studio is separated from Green-Grade Cemetery by a single brick wall, and during a late-night studio party on the eve of Halloween, the screenwriter receives a note that “a great revelation awaits” him on the other side of the wall: “material for a best-selling novel or terrific screenplay.” A timid soul, he hesitates but cannot resist. There he finds a body — or is it? Because the body is that of a studio head who supposedly died twenty years ago.

A Graveyard for Lunatics centers around the solving of the mystery, but it’s primarily of interest to fans as a lengthy roman à clef of Bradbury’s time working on King of Kings. Famous Hollywood figures appear, operating under pseudonyms, such as the screenwriter’s best friend, special effects master Roy Holdstrom (obviously Bradbury compatriot Ray Harryhausen). Even Jesus Christ (called J.C., resident of 911 Beechwood in Hollywood) is a prominent character, given his starring role in the film.

Though inspired by hard-boiled works, Bradbury’s protagonist/alter ego is as soft-boiled as you can get. He’s a sweetheart, an innocent — when Constance Rattigan arises nude from the sea, he looks her in the eyes — a bright child in a man’s body. (Yet he’s completely up to the task of a heart-racing fight to the death underwater.) The tone more closely matches that of Agatha Christie, but Graveyard is a solid mystery as only Ray Bradbury could write it.

In 2003 Bradbury revisited Elmo Crumley and company with Let’s All Kill Constance. In the opening, Constance Rattigan comes into the Bradbury character’s home bearing two books: a 1900 telephone directory and her own personal address book. Some names in both books are crossed out entirely: these are names of those no longer of this earth. Others are circled with a cross beside them, one of them Constance’s, and she believes that this means she is one of the next to die. On leaving the books with the writer, she disappears.

Let’s All Kill Constance is not quite as good as its predecessors, but any Bradbury is worth reading. His particular style is always welcome, its familiarity alone bringing a level of comfort to the experience — like revisiting an old friend. The mystery itself is not as interesting as the characters and their relationships with each other. Although it feels at times (as with afemale impersonator) that Bradbury is simply creating a character to fill his plot needs, he still makes each real enough to justify the time spent with them.

The bulk of this third novel concerns the search for Constance. Teaming up again with detective Elmo Crumley, the writer meets several people involved with Constance’s past (many of whom she has just left when the writer and Crumley arrive) and puts together the pieces into a disturbing yet satisfying solution illustrative of the difficulties inherent in being a Hollywood actress.

But through all this Bradbury’s youthful exuberance shines. The writer’s enthusiasm for life comes through as unadulterated innocence. He seems not to be jaded at all by the modern world, and so these books are not as “noir” as they would have been in other hands. And yet, it’s refreshing to have a noir hero who’s not a person whom the world has not made a pessimist.

Where Everything Ends is a trio of fine detective novels (together with the short story that provided the starting point) from Bradbury in his inimitable style. He plays with the conventions, but since he so obviously loves the genre, this is easily forgiven — embraced, even — because the end results are, simply put, fine additions to the canon. This series is also dear to fans because it is likely the closest thing to an autobiography we will receive from this man who has brought so much joy to so many people for so many years.

(Subterranean Press, 2009)