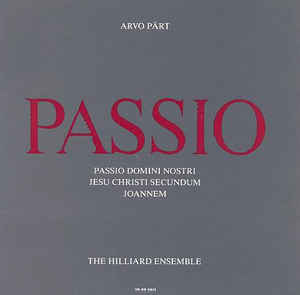

Arvo Pärt’s Passio was the first recording of his music that I owned. It may very well have been the first available in the U.S. For one entire summer it was my beach music — I tended to go to the lake shore early — the combination of Pärt’s magnificent oratorio and the early morning sun is very hard to describe. Passio pretty much cemented my fondness for the composer’s music. (And this was in the days when tape cassettes and the Walkman were cutting edge.) It’s an oratorio on the Passion of Christ, based on the story as told by St. John.

Arvo Pärt’s Passio was the first recording of his music that I owned. It may very well have been the first available in the U.S. For one entire summer it was my beach music — I tended to go to the lake shore early — the combination of Pärt’s magnificent oratorio and the early morning sun is very hard to describe. Passio pretty much cemented my fondness for the composer’s music. (And this was in the days when tape cassettes and the Walkman were cutting edge.) It’s an oratorio on the Passion of Christ, based on the story as told by St. John.

Pärt is very much aware of the role the listener plays in the experience of his music. He has said “I would compare my music to white light which contains all colors. Only a prism can divide the colors, and make them appear; this prism could be the spirit of the listener.” There are, perhaps, a couple of filters through which one can evaluate this statement. There is a strong tradition of choral singing in the Baltic countries, much as in neighboring Scandinavia. (In case I haven’t mentioned it before, Pärt is Estonian.) There is also a strong tradition of choral singing in the music of the Church, which was repressed under Soviet rule (Pärt’s music was banned). That might provide some basis for the composer’s focus on religious works for chorus in his music since the 1970s.

For the Passio, “white light” seems a particularly apt metaphor: it’s a transcendent work in which the “white light” often becomes a wall of sound — the aural equivalent, perhaps. The full choral passages, composed in Pärt’s characteristic triads, can be almost overwhelming. The melodies are, as usual, quite spare, although the composer infuses a great deal of dramatic tension into the work. And yet, underlying this transcendent and sometimes overpowering music is simple, honest grief, which, it occurs to me, is an emotion quite rare, if it is to be found at all, in liturgical music.

That simple grief is mirrored in the sadness Michael George brings to the role of Jesus. I found the decision to write the part of Jesus for bass somewhat strange, but George brings it off, beautifully, to the extent that you can hear not only the sadness but the realization of the inevitability of what is to come. It’s immensely moving in itself, and set against the backdrop of the choral passages, it brings a human reality to the Passion that I can’t remember hearing anywhere else.

I’m not sure, thinking about it, that Pärt is completely correct about the “white light” metaphor: Listening again, after admittedly a few years, it seems that the composer has put more into the music, more specific content, than he might be willing to admit. Religious music has always been among the strongest and most appealing music made, and that is true no less today than it has been in the past. There is a reason that music, ritual, and worship are so inextricably tied together all over the world, and that reason seems to reflect something fundamental in the human need to believe.

The Passio may not be the “best” work by Arvo Pärt, neither the most difficult nor the most intellectually challenging, but it is certainly one of the most compelling. In fact, in the range of contemporary art music, it is one of the more accessible works by a major composer, and one that is not only worth having for its own sake, but one that will, I think, lead the listener to investigate more fully the range of possibilities in the best music of today.

The Hilliard Ensemble has an excellent history with Pärt’s music, and I really can’t point to any flaws in this recording, which is up to ECM’s usual high standard. I might have enjoyed a little more information accompanying the disc, but on the other side of the coin, I was able to come to it originally without preconceptions.

(ECM New Series, 1988)