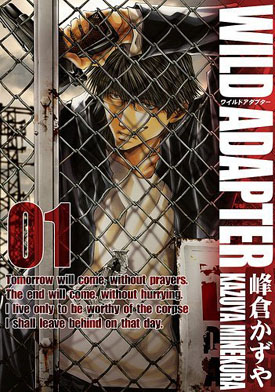

Kazuya Minekura is a well-known manga artist responsible for, among other things, Saiyuki and Araiso Private High School Student Council Executive Committee, which I have only seen in anime and which, believe it or not, is directly relevant to Wild Adapter, her newest manga series.

Kazuya Minekura is a well-known manga artist responsible for, among other things, Saiyuki and Araiso Private High School Student Council Executive Committee, which I have only seen in anime and which, believe it or not, is directly relevant to Wild Adapter, her newest manga series.

Araiso introduced us to two characters, Makoto Kubota and Minoru Tokito, whom Minekura has transplanted to a new universe for Wild Adapter. Kubota had a brief career with the Izumo Group’s youth gang (we’re talking yakuza here — not nice people) until he starts hearing about “W.A.,” a new drug on the streets. The side effects of W.A. are bizarre. One of the most notable is death; another is that the dead have been transformed into something clawed and furred and no longer completely human. Kubota also stumbles across Tokito, whose right hand is clawed and furred (he wears a glove on that hand, as he did in Araiso, although we never knew the reason there) and who is fleeing from someone. Again, we don’t know who. In fact, there’s a lot we don’t know, but then, neither does anyone else.

Minekura’s appeal is hard to explain, and I readily admit I’m a fan, or as close as I ever come to fandom. In part it’s her quirky drawing, about which more later. Another part is her complex, knotty stories, coupled with her genius at revealing character. And part is the attitude reflected in her work.

That attitude is a big part of the meat of Saiyuki and Wild Adapter. In Saiyuki there is a certain in-your-faceness to the whole thing that comes from subverting our expectations (which also reveals a certain satirical bent) — a very holy Buddhist priest who carries a pistol, smokes, drinks, and gambles; or the half-breed demon who demonstrates a depth of compassion rare in anyone. In Wild Adapter that quality becomes more elementally surreal: we don’t know anything, and the characters don’t know anything, because this universe doesn’t allow for explanations. And the universe doesn’t play fair. Very early on, Kubota says: “Even if I was cheating, you’re still a loser for not catching me at it. Those are the rules of the world, right?” There’s our theme, ladies and gentlemen, or at least a chunk of it (this series is much too complex to be summarized so neatly).

And so Kubota, and perforce Tokito, embark on the search for Wild Adapter. It helps that Kubota’s uncle, Kasai, is a police detective working on the same thing. Well, it helps a little — the two don’t always see eye to eye.

Kubota is the central character here, at least so far. And like everything else in this series, he’s a puzzle wrapped in an enigma. Still in high school (at least nominally — no one’s seen him near a school), he’s a cold-blooded murderer who is also a whiz a mahjong, has no particular interest in women or men, loves the latest new thing, and takes the time to bury a dead stray cat. Tokito is also a puzzle, but there’s an obvious reason for that: he doesn’t remember anything.

The series is episodic, as might be expected — it’s a set of leads that don’t pan out. The local yakuza are looking for the source, as well — they want in on it, but they’re coming up blank. There’s a cult that looks promising, but they don’t know anything either. Kubota gets hauled in by the police, who think he knows something; he doesn’t, and his uncle Kasai gets him out. Even the unlicensed doctor, Kou, for whom Kubota works part-time, doesn’t have any leads.

One of the core elements here is the relationship between Kubota and Tokito, which seems to be prickly — at least to start — but very intimate. Minekura is one of those artists who will play with boys’ love elements a story, which does create a certain amount of tension. She fills us in on the relationship in Volume 5, which takes place between Volumes 1 and 2 and is narrated by a schoolboy, Shouta, who is as much a misfit as either of the protagonists. It’s a nice device, in part at least because for the first time we know things that the narrator doesn’t.

Minekura’s drawing style is quirky and unique. Although her character designs come from the bishounen aesthetic — slender, long limbed and somewhat androgynous — they are distinct individuals, as quirky and eccentrically portrayed as might be expected in a story this singular. Although layouts are more frame-follows-frame than not, Minekura makes use of a full complement of devices to impart a definitely cinematic feel to the narrative.

Wild Adapter is very much dark-side, even for manga, which has a tendency to deal very matter-of-factly with things that most Western comics avoid. I have to confess, though, that I’ve never been so entertained by the portrayal of nihilism. It’s an ongoing series (Volume 6, which I’ve somehow missed acquiring, is out; Volume 7 is still being serialized in Japan.)

(Tokyopop, 2007-2008)