Robert Wiersema penned this review.

Robert Wiersema penned this review.

Anyone who has spent any time with a child, or with a children’s book, will realize that a child’s sense of humour, and of reality, tends toward the gloriously demented. In the open, amorphous, formative state of the early years, when language and meaning are fluid, the artificial boundaries which we as adults find ourselves so hemmed in by are utterly absent. How else to explain a child’s love for the works of Dr. Seuss, or for Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth? Every child is a gleeful surrealist, at least until the world beats it out of them, through the process commonly (and with a dangerous banality) referred to as “growing up.”

Some adults, however, don’t seem to have taken the bruising quite as badly as most. The lessons don’t seem to have quite stuck. Their imaginations skip freely from point to point, deftly defying arbitrary restrictions and boundaries, keeping their vision of their art foremost in their mind, and paying little heed to those who would try to rein them in. Think of Klimt, or Picasso. Miles Davis, or John Coltrane.

Think of Neil Gaiman.

The transplanted English fantasy writer (see how reflexive it is to categorize, without even considering it), based in the United States for over a decade, has made a career of leaping through the imagination and across genres and forms as varied as straightforward novels and short stories, radio plays, screenplays and graphic novels. No matter the genre, what always comes to the fore is Gaiman’s sweeping vision, and his great sense of, and love for, story in its purest, least adulterated form. While most of his adult writing folds in on itself to both reference and include varying mythologies, religions, folk tales and motifs, and figures that could only be drawn from dreams, his first foray into writing for children is more down to earth: a sunny afternoon, playing in the yard. A boy and his sister. A friend and his goldfish. A father who “doesn’t pay much attention to anything, when he’s reading his newspaper.”

Of course, as any child will tell you, from these such innocent things do great adventures come.

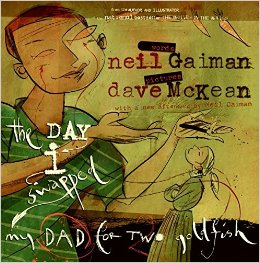

With The Day I Swapped My Dad For Two Goldfish, Gaiman fully embraces his inner juvenile surrealist. While the cover promises the books “will delight anyone who is — or has ever been — a kid,” Gaiman goes further than delight. Reading this book, an adult will be plunged back into a child-like frame of mind, a reality, once coloured in Seuss-ian bolds, now vivid and starkly rendered by Gaiman’s long-time friend and frequent illustrator Dave McKean in line drawings, collages and bold washes.

When his friend Nathan brings two goldfish to our narrator’s house, he MUST have them. He tries to trade away baseball cards, an old robot, a punching bag and a penny-whistle, but to his horror, “Every time I showed him something, Nathan said ‘No’.” Every time, that is, until he offers Nathan his father in exchange. “He’s bigger than your goldfish,” he argues, adding that he can swim “better than a goldfish.” His sister refutes this claim with a terse “Liar,” but it’s too late. The deal made, Nathan takes home the narrator’s father, and all seems fine until his mother comes home, and, after ungagging the sister and finding out the truth, demands the trade be undone. Unfortunately, Nathan has already traded away the father for an electric guitar, and our narrator, accompanied by his little sister, undertakes an epic voyage of wheeling and dealing to return his father safely home.

While McKean’s visuals are tremendous (the vision of the father in a rabbit hutch is unforgettable, and the textured collages which form the backgrounds to many of the illustrations are key narrative and thematic elements themselves), the story belongs to Gaiman. With the wry worldliness of Tom Sawyer, the sly surrealism of Dr. Seuss and the rhythmic narrative quality and matter-of-factness of P.D. Eastman’s Are You My Mother?, Neil Gaiman’s The Day I Swapped My Dad For Two Goldfish is simply a treat, a journey back to a simpler time in the hands of one of our most creative voices.

(Borealis, 1997)