Jayme Lynn Blaschke penned this review.

Jayme Lynn Blaschke penned this review.

Walk into a bookstore–any bookstore–and take a look at the titles lining the shelves of the fiction section. Odds are there won’t be too many short story collections, and more’s the pity. In today’s corporate-minded climate, short story collections don’t promise the high-profit return offered by the mega-selling novels of the Tom Clancys and John Grishams of the world, so most publishers simply ignore them. Table scraps for the small press, so to speak.

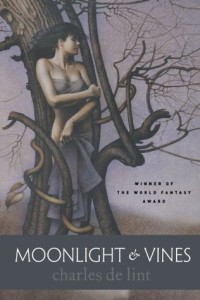

It says something, then, when a major publisher–in this case, Tor Books–devotes itself to a major hardcover release of such a collection. Of course, when that collection happens to be Moonlight and Vines–the third volume in Charles de Lint’s ever-growing Newford chronicles–the call’s an easy one to make. Both of his previous collections, Dreams Underfoot and The Ivory and the Horn, remain in print, and de Lint’s loyal readers snatch up his stories whenever they show up in anthologies or the genre magazines. Needless to say, Moonlight and Vines is a must-have for those familiar with de Lint’s work, as well as newcomers to his distinct flavor of urban fantasy.

The stories in Moonlight and Vines take place–like almost everything de Lint writes nowadays–within the mythical North American city of Newford. The usual cast of characters is here, with Jilly Coppercorn and the Riddells–Geordie and Christie–leading the way. Even Bones, the enigmatic Native American Trickster figure from de Lint’s 1997 novel Trader puts in an appearance in the heartfelt “Wild Horses.”

Perhaps the most intriguing of the new offerings is “Shining Nowhere but in the Dark.” Eventually published in Realms of Fantasy, “Shining” was originally written for Neil Gaiman’sSandman: Book of Dreams anthology, but was withdrawn when Time-Warner demanded full copyright ownership–which conflicted with de Lint’s already-established copyrights on Newford and various characters. The revised version features the Fates of classic mythology, but it doesn’t take much imagination to replace them with Dream, Death and the rest of the Endless from the popular DC comic. It’s clear de Lint had a good grasp of the characters and had fun in Gaiman’s playground, making the resulting story that much more Time-Warner’s loss.

Another comic-related story is “If I Close My Eyes Forever,” which originally appeared as a collaboration with Charles Vess in Mojo Press’ massive comic anthology Weird Business. Minus Vess’ artwork, the rewritten tale is more philosophical and introspective than the original version, which was pretty spare with the narraration, relying on imagery to evoke mood. Surprisingly, both versions hold up well, and are different enough to stand on their own.

A real treat for readers is the inclusion of four tales – “Crow Girls,” “Heartfires,” “My Life as a Bird” and “The Fields Beyond the Fields” – previously available only in the form of limited-edition Christmas chapbooks. Unlike the commissioned work de Lint does for theme anthologies, there are no outside constraints on these stories, and there’s a sense of experimentation and fun about them that not all of the other tales in this book share. Now these stories don’t always work to perfection, but that’s excusable, since they’re still a pleasure to read. “Heartfires” is perhaps the strongest of the four, a hard-to-classify piece that examines the shadowy ground where reality and stories converge, with a good dose of Native American mythology thrown in for good measure. “My Life as a Bird” is a fun, silly romp that breaks no new ground with its take on the traditional frog prince theme of fairy tales, but it’s such a joy to read that nothing more is needed. “Crow Girls” leaves the reader wanting the rest of the story, and could be viewed, in fact, as a test drive for the characters which would later show up in de Lint’s 1998 novel Someplace To Be Flying. And the book’s closing piece, “The Fields Beyond the Fields,” is a somber character study of recurring character Christie Riddell, a man who lives with and writes about magic and myth, yet struggles to hold onto his own belief in the fantastic. Taken with the other Christie Riddell story contained here, “Saskia,” which opens this volume, the two stories provide enchanting, understated bookends.

The only real disappointments are “In the Pines,” a ghost story that never really develops a reason for being beyond an infuriating “Oops, never mind” ending, and “China Doll,” written for the anthology The Crow: Shattered Lives and Broken Dreams. Unlike the resonant myth of Gaiman’s Sandman, de Lint’s hopeful, humanist style clashes uncomfortably with the nihilistic themes of the ultra-popular, ultra-violent Crow movies and comics. No stranger to horror, de Lint probably would’ve had better luck had he written this story on his own terms and not followed the constraints imposed by the anthology–but since the anthology is the only reason this story exists in the first place, that’s pretty much a moot point.

Despite its flaws, Moonlight and Vines is a worthy addition to the de Lint canon. With a heavier emphasis on Native American mythos and a near lack of Celtic themes, this volume stands apart from Dreams Underfoot and The Ivory and The Horn. And while Moonlight and Vines never quite achieves the lofty sense of wonder evoked by Dreams Underfoot -what could?–it only serves to reenforce the notion that de Lint is at his best when writing the short form.

(Tor Books, 1998)