Matej Novak penned this review.

It is quite an injustice that Neil Gaiman is so often regarded only as a writer of comic books and graphic novels. But there are also those people — perhaps familiar with his short stories, novels or other works — who are under the impression that Gaiman’s work in comics begins and ends with The Sandman, and are, in the process, doing him just as great a disservice. For Gaiman is a storyteller, one who time and again transcends genre and style. Harlequin Valentine not only demonstrates his remarkable ability to bring together diverse elements, but also highlights the range of sources he draws on to bring his tales to life.

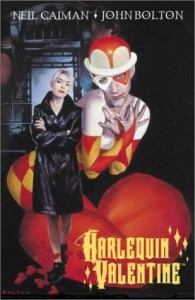

The thirty-two page hardcover graphic novel again teams Gaiman with artist John Bolton — who previously worked with the writer on the 1990 miniseries The Books of Magic — and is based on Gaiman’s own short story of the same name. That story — which has appeared in several anthologies and is available on the 2003 CD Telling Tales, read by the author — is itself based on a sculpture by Lisa Snellings, to whom Harlequin Valentine is dedicated.

Got all that? Perhaps it would be best — at least where plot and subject are concerned — to begin at the end, which in turn brings us to the beginning, several hundred years ago.

The story draws on the conventions of harlequinade, or English pantomime, a theatrical form which began in England in the 18th century as a variation on Italian commedia dell’arte. The origins of that reach back even further, thousands of years, to the Romans and Greeks. All of this Gaiman explains in “Notes on a Harlequinade,” an eight-page afterword to the volume, which begins with a definition of Harlequin, our titular hero:

A buffoon, dressed in parti-colored clothes, who plays tricks, often without speaking, to divert bystanders or an audience; a merry-andrew; originally, a droll rogue of Italian comedy.

And later, in the words of E. Cobham Brewer’s Guide to Phrase and Fable: “Harlequin, in the British Pantomime, is a sprite supposed to be invisible to all eyes but those of his faithful Columbine.”

Ah, yes: Columbine. The story begins with Harlequin pinning his heart — literally — to the door of his beloved Columbine, whose name in this case is Missy. Now, let’s not forget that we are in Neil Gaiman’s world, where the pinning of a heart to a door does not necessarily constitute anything strange. Harlequin Valentine being a contemporary tale, however, it is Missy’s reaction to discovering the heart that is curious, to say the least: she calmly, casually puts it in a plastic bag and sets off to discover its origins. Harlequin proceeds to follow her, and we are sucked in, just like that.

It is not, however, merely the circumstance of the story’s opening that makes us want to read on. It’s also Gaiman’s language, his style, his storytelling, all augmented by Bolton’s wonderful artwork.

Gaiman manages to give Harlequin a stylized manner of speech that is at once lofty and accessible. In the story’s opening lines, for example, he refers to the men who have left their homes on this February morning’s “Great Commute” as “steambreathing and greatcoated,” a line miraculously poetic in its simplicity. Later he spends a page with an incidental character, a secretary, in an aside that is at once heartbreaking and heartwarming, not to mention unforgettable. And not to be outdone, Gaiman writes two panels — each taking up an entire page — leading into the story’s coda, during which the story changes so subtly yet so completely that the moment will haunt you when it’s all over.

All the while Bolton paints images that linger and creep along the border of the real and the fantastical. Faces look like photographs, backgrounds are blurred and impressionistic, vibrant reds — the heart, blood, Harlequin’s costume — play against dusty shades and pastels. It is like looking at a dream, or more precisely, at that moment of a dream just before waking, when the perceived reality just begins to fade into hazy memory. His are the perfect magical visuals to match Gaiman’s magical tale.

The rewards of reading Harlequin Valentine are as much a part of the process, the journey, as they are of the outcome. And coming from Neil Gaiman, even a simple love story is bound to have more than a few surprises. Writing about Harlequin in his own words, Gaiman offers a little more insight into the character, perhaps even into his allure:

There are those who trace Harlequin back to the phallophores in the Roman comedies, clutching giant phalluses, their faces blackened with soot. There are others who point to his name for clues as to his true origin: the French herlequin was a kind of spirit, a sprite, a will o’ the wisp; arlechino the name of a devil; and most lexicographers, as you will see from the definition which prefaces this afterword, derive Harlequin straight from Hell…

(Dark Horse, 2001)