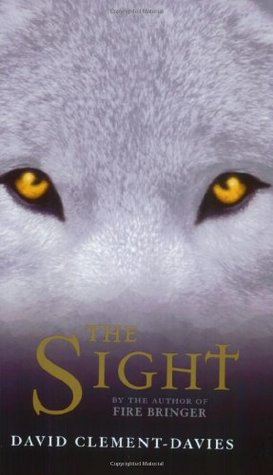

The Sight is the second fiction offering from travel writer David Clement-Davies. His first novel, Fire Bringer, was set in Scotland and centered on red deer. The Sight takes us to medieval Transylvania and gives us the story of a pack of wolves. As with Rannoch the deer in Fire Bringer, Clement-Davies centers this book on Larka, another animal Messiah.

The Sight is the second fiction offering from travel writer David Clement-Davies. His first novel, Fire Bringer, was set in Scotland and centered on red deer. The Sight takes us to medieval Transylvania and gives us the story of a pack of wolves. As with Rannoch the deer in Fire Bringer, Clement-Davies centers this book on Larka, another animal Messiah.

Larka is a young white wolf born with the Sight, a psychic gift that allows the bearer to not only see the future and to see through the eyes of birds, but to control the minds and actions of other beasts. Another Sighted wolf, Morgra, curses Larka’s family pack. Morgra is an outcast from the pack, a bitter angry wolf with a grudge. She wants Larka to use her power for evil purposes. The Sight follows Larka’s struggle to master her power and her battle against Morgra.

When I read Fire Bringer I had hopes for Mr. Clement-Davies future works. The Sight was a huge disappointment. This book is a mess.

The wolves depicted here are not wild animals. These beasts are desperately, hideously anthropomorphized. Aside from the few details about wolf behavior that seem to have been culled from Ranger Rick magazine and then dramatized for effect, these wolves are virtually furry people. We meet a wolf with an inferiority complex, a wolf with a guilty conscience, a depressed wolf, a wolf frustrated by infertility, a wolf falsely accused of child abuse and murder: these wolves don’t need a Messiah, they need a therapist.

At one point Larka becomes severely depressed. Having experienced the mind of a prey animal from the inside (thanks to the Sight), she is unable to hunt for her food and is starving herself. We are treated to an edifying scene of what can only be described as wolf psychotherapy, as Larka converses with an eagle named Skart:

“It is possible,” cried Skart, circling right above her head again and again, “to kill without hate. To kill, quickly and cleanly, with compassion.”“Compassion?” It suddenly seemed to her the most beautiful word she had ever heard.

“And to feel compassion for other things, you must learn to feel compassion for yourself too.” The young wolf felt a lightening in her, as though she was being given permission.

“Larka, you have done nothing wrong.”

Larka was so startled that the fur on the back of her neck quivered. It was as though a paw had slapped across her muzzle. She suddenly knew what she had been running from for so long. It was guilt.

Ugh. All we’re missing here is creative visualization for Larka’s inner puppy. There’s plenty of this silliness to be found in The Sight.

Unfortunately, Clement-Davies also decides to use the Savior concept again, only this time we get two for the price of one. Larka is clearly a Christ-figure who must sacrifice herself for her “people”. Why this is necessary is beyond me since the wolves already have a Christ called Sita, a wolf sent by her wolf-god parents Tor and Fenris to save wolfkind. In fact, not only does a wolf recite the religious gospel of Sita, the author also includes a version of the Little Red Riding Hood tale morphed into a sort of wolfish Cain and Abel story.

In addition to multiple Christs, Clement-Davies is not satisfied with one villain. No, The Sight has three. In addition to Morgra and her minions, there is an angry she-wolf called Slavka hunting Larka to prove that the Sight is a myth. There is also a mysterious evil called Wolfbane. Wolfbane is the wolf version of Satan, incarnated and slave to Morgra. I might note here that the identity of the creature channeling Wolfbane is pathetically clear from the first moment Wolfbane appears and is the least surprising “twist” in the book.

Continuity here is bizarrely hit and miss. For example, Larka is born as part of a litter, and only 2 of the 4 pups are born alive. Larka’s mother Palla tells her mate, “It is nature’s way, Huttser…we must look to the living now. The pack must survive.” Yet later, when another cub of Palla’s dies, the she-wolf is consumed with anguish. She thinks “There is nothing more terrible…than for a child to die before its parent.” Well, which is it?

To make a long story short (and I wish Clement-Davies had made this overly long story short), The Sight is a terrible book. There are too many characters, and most of them aren’t around long enough for us to care about them. Personalities are caricatures with traits pulled straight from the self-help bestseller list. The plot is unnecessarily convoluted, and while I can generally read a book of this size in a day or two, it took me weeks to get through The Sight because it just couldn’t hold my interest for more than half an hour at a time.

I hope that Mr. Clement-Davies will continue to write his wonderful travel pieces, but I certainly don’t look forward to anymore novels from this author.

(Dutton Books, 2002)