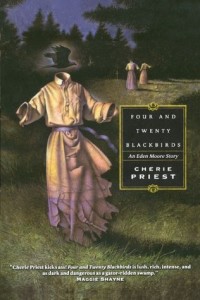

Cherie Priest is a first time novelist. However, she writes with ease and a deceptive power, like the flow of the Tennessee River through her home city of Chattanooga. Four and Twenty Blackbirds is a Southern Gothic with a hint of hard boiled mystery: there’s grit in the magnolia honey and in the heroine as well.

Cherie Priest is a first time novelist. However, she writes with ease and a deceptive power, like the flow of the Tennessee River through her home city of Chattanooga. Four and Twenty Blackbirds is a Southern Gothic with a hint of hard boiled mystery: there’s grit in the magnolia honey and in the heroine as well.

Southern Gothic at its best — and this book is right up there — is not just horror stories. It is a reflection of oral history and family legends, the kind of story a child learns while playing around the feet of aunties and grannies at the stove: sometimes warmly familiar, but sometimes dark and full of dubious spirits. Though I’m a native Californian, I heard stories like this from my own mother, on rainy afternoons in a kitchen redolent of fresh bread and the starch-water she sprinkled on the ironing. . . . These tales are largely women’s stories. They are universal, but in Southern Gothic they find an irresistible modern voice. It’s the choral voice of all the ladies who ever wrapped the family history in myth and innuendo, and spoon-fed it to their daughters.

Priest is a new voice in this chorus and she sings a remarkable debut solo in Four and Twenty Blackbirds. This is a splendidly entertaining, idiosyncratic book.

The story is set in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where its heroine, Eden Moore, grows up seeing ghosts. This doesn’t strike either Eden or her family as especially odd — lots of ghosts to see in the South, and lots of wondering kids’ eyes to see them — but in the genteel neighborhood where Eden lives, it’s not something mentioned in public. That doesn’t bother Eden, either; little girls catch on fast to the things that shouldn’t be discussed outside the home. Her wry child’s voice describing the balancing act required to hide her visions from school and summer camp is hilarious, though.

Eden grows up as the adopted daughter of her mother’s elder sister. There’s no secret there: Eden’s mother died in childbirth, and so her Aunt Lulu took her in. No one has ever tried to hide this from Eden. What they have hidden is an entire reef of family secrets and insanities that mature with Eden, and finally threaten to tear her life to bits in her twenties. And that is the meat of the story, as Eden tries to deal with the mysteries that have permeated her family’s activities for 165 years. If she fails, both her own life and her beloved Aunt Lulu’s will be forfeit.

The Moore family (mostly white, but technically black) has evolved in tandem with the Dufresne family (mostly and technically white), in the kind of bi-racial symbiosis only found in the South. Eden’s introduction to the other branch of her family comes when she is eleven, and her religious maniac cousin and/or brother Malachi tries to murder her. Malachi believes Eden is the reincarnation of their mutual ancestor Avery, who was a DuFresne slave and a necromancer. He may also have been their great-great grandfather and/or uncle. The confusion over the exact family relationships is of a piece with their entire history, as Eden eventually discovers — fathers married entire sets of sisters, or fathered children in both lines of the entwined family. And hardly anyone has had the good grace to actually die . . . until Eden’s generation, where the daughters of Avery are suddenly dropping like ripe fruit into a swamp.

Eden’s desperate quest to find out why, and prevent it, leads her through a haunted sanitarium (where she turns out to have been born); the ancient mansion and graveyard of her Defresne relations; and a myriad coffee houses, modest motels and cheap restaurants (Eden never met an IHOP she didn’t like). It reaches its climax, though, in the crowded, haunted environs of St. Augustine, Florida. That city has housed the oldest settlements of both Europeans and Africans in the New World; and in Eden’s South, they live disturbingly on.

This really is a grand little ghost story, and rises above the morass of the genre by virtue of Priest’s beautiful prose and dialogue. Eden is a sharp-tongued, thoroughly modern young lady. Her ruminations on the practical problems of seeing ghosts, hiding boot knives or choosing bustiers all have a marvelous dry humor. The atmosphere is appropriately dark and steamy, but it is free of the enervating languor sometimes found in Southern Gothic; Eden is a lively protagonist, and the real life of the countryside is lovingly invoked. For the reader, as for Eden in her desperate family research, the past is dreadfully alive.

The weight of women’s stories, through the aunts and sad sister ghosts, falls very gently over the reader at first. As the book progresses, it weighs more and more heavily, like an antique shawl freighted with stones. For all its Gothic trappings, I didn’t find the story to be frightening — except in that very special way that all families are frightening: and in that area, it is terrifying indeed.

(Tor, 2005)