A Fine and Private Place is a layered temporal paradox, a bit of separate space/time that twists off the main stream into a sparkling little soap-bubble universe of its own.

A Fine and Private Place is a layered temporal paradox, a bit of separate space/time that twists off the main stream into a sparkling little soap-bubble universe of its own.

First paradox: It’s about life after death, and life during death, and life instead of death. Death comes at different times to the characters in the story, and more than once for some of them. Some of them live through it. Some recover. Some never notice.

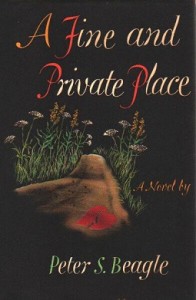

Second paradox: It is Peter S. Beagle’s first novel, but most people don’t read it until after they have already read his second, the wildly popular fantasy classic The Last Unicorn. To this day many of Mr. Beagle’s fans are unaware of A Fine and Private Place, unless they have tracked down an old 1969 Ballantine paperback, or one of the subsequent reprints (Del Ray 1980 or Roc 1992, for example).

Third paradox: A Fine and Private Place was published when Mr. Beagle was 21; he wrote it when he was only 19. This would be amazing even if it had been a bad novel, since college seniors don’t ordinarily get their books published by major houses. But it’s not a bad novel. It is a superb one. The paradox is how a work of such wisdom, humor and compassion — qualities that are not usual in adolescence — was written by someone barely out of childhood. It is an act of prodigy. Or maybe time travel.

A Fine and Private Place is also a marvelous work of magical realism, written some seven years before Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude made the form commonly popular in world literature. The concept of magical realism was originally invented by Franz Roh in 1925, to describe post-impressionist painting, because it revealed the mysterious elements hidden in everyday reality. It applies beautifully to this book, which is rich with Mr. Beagle’s skillful combination of reality and delicate dreams.

The plot, for those who never got past The Last Unicorn (and shame on you, if so!): Jonathan Rebeck is a failed druggist. 19 years previously, he went on a monumental bender after losing his pharmacy to bankruptcy, and woke up inside a very large cemetery located in the Bronx. He has never left. He isn’t dead, though; he just lives there, sleeping in a mausoleum and depending on a cynical talking raven for food and the odd paperback book. (As the raven tells Rebeck: “Ravens bring things to people. We’re like that. It’s our nature. We don’t like it.”) Rebeck has dropped out of society. He would be a fugitive, except that society has never even noticed that he’s gone missing. Only the dead know he’s there, but they forget.

The dead, it appears, do not waft off to Heaven or Hell. They just stay put, trapped within the boundaries of the graveyard where they are buried, and gradually forget their lives, their faces, their shapes. They fade. But until they vanish completely, Rebeck keeps them company. He talks to them, reads to them, plays chess with them, sits with them and provides an ear while they talk and forget and eventually disappear. “I think of it more in the nature of being a night light, a lantern down a dark street,” is how he describes it to the recently dead Michael Morgan.

Michael is full of energy and outrage. He didn’t die, he points out — he was murdered, poisoned by his lovely wife, and is therefore determined not to fade. By contrast Laura Durand is also newly dead, but more relieved than sorry. She gratefully embraces the idea of dissolving into nothingness. Neither of them, however, is quite succeeding: try as he might, Michael is slowly forgetting things; while Laura finds she cannot lie down and rest. And they bother one another. The result is as inevitable and exquisite as crystals forming in a geode. It may not be alive, but it’s beautiful.

In the meantime, Rebeck has his own sudden problem in the person of Gertrude Klapper, who came to the cemetery to visit her dead husband Morris, but now keeps finding reasons to come back to visit with Rebeck instead, whom she thinks is just another person who comes there a lot, like herself. Rebeck is afraid to tell her the truth, afraid of the world outside the cemetery which she represents, afraid to face his fears about the idea of leaving…and now, making matters worse, he has also finally been noticed by the night guard, Campos .

As in all of Peter Beagle’s stories and books, A Fine and Private Place is a gorgeous piece of writing. Mr. Beagle is a wordsmith of consummate skill, and there are almost no signs of apprentice work here. The exposition is a little fast, perhaps showing the impatience of a young man to get to the meat of the story, but it doesn’t rush one too much. The humor is subtle and tender. All the characters are detailed and real; a little symbolic, perhaps (he was 19, after all), but three-dimensional nonetheless.

The central themes of the story are enormous — love and death, what else is there? — but they are explored with a power so controlled it seems easy. The reader is relaxed, lulled, and then emotionally ambushed: because Love does not last forever, and Mr. Beagle is ruthless in abiding by the laws of his chosen universe.

The title, as you all should know, comes from Andrew Marvell’s To His Coy Mistress. Here is a link to the full text, which you should read. Now. For the good of your intellect.

Beginning writers are told, “Write what you know.” They don’t always, of course, which sometimes produces amazing worlds and stories. Whichever of these rules Mr. Beagle followed, the results were splendid. We should all be grateful.

(Viking, 1960)