When I was a child — long, long ago, eons before GUIs, desktop publishing and digital cameras — I loved taking tours of historical old houses. One of the highlights of touring such old places, aside from the wonderful old architecture and the haunting atmosphere, was that last stop at the gift shop. Every historic landmark had some eccentric self-published pamphlet about the site, which always provided arcane bibliographies, scandalous tidbits concerning local historical figures, and legends of ghosts or other spirits. I had entire collections of these booklets and pamphlets, each charmingly unique and created with obvious love of the place and the subject. Carol Ballard’s chapbook about the Green Man and his connection to Shakespeare reminded me vividly of those unique little books.The Green Man, for anyone who may not have had the slightly spooky pleasure of being introduced to him before, is considered to be the spirit of vegetation, fertility, and rebirth. He can be seen in one of the oldest British manuscripts, “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” translated most memorably by J. R. R. Tolkien; and from Susan Cooper’s wonderful Greenwitch to the recently published anthology The Green Man: Tales from the Mythic Forest, edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling.

When I was a child — long, long ago, eons before GUIs, desktop publishing and digital cameras — I loved taking tours of historical old houses. One of the highlights of touring such old places, aside from the wonderful old architecture and the haunting atmosphere, was that last stop at the gift shop. Every historic landmark had some eccentric self-published pamphlet about the site, which always provided arcane bibliographies, scandalous tidbits concerning local historical figures, and legends of ghosts or other spirits. I had entire collections of these booklets and pamphlets, each charmingly unique and created with obvious love of the place and the subject. Carol Ballard’s chapbook about the Green Man and his connection to Shakespeare reminded me vividly of those unique little books.The Green Man, for anyone who may not have had the slightly spooky pleasure of being introduced to him before, is considered to be the spirit of vegetation, fertility, and rebirth. He can be seen in one of the oldest British manuscripts, “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” translated most memorably by J. R. R. Tolkien; and from Susan Cooper’s wonderful Greenwitch to the recently published anthology The Green Man: Tales from the Mythic Forest, edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling.

What one notices in reading each of these stories or collections of stories is the Protean nature of the Green Man or Green Woman. The Green Man can represent fertility, the life force, death and rebirth, pagan worship of the forest, or the dark side of one’s own archetypal forest. What Carol Ballard points out is that, while the Green Man existed as an architectural image and a source of story during Shakespeare’s time, the archetype of the Green Man has found increasing popularity in the twentieth century. Ballard makes a direct connection not only between Shakespeare and the Green Man, but between creative artists in the twenty-first century and the Green Man. It seems that the more human beings are reliant on the sometimes sterile resources of urbanization and technology, the more we require a a figure which manifests our own need to express creative desire, what Ballard refers to as “expressions of human longing for the greening and reawakening of life.”

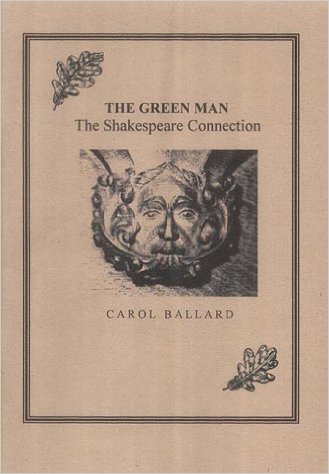

Ballard does not limit herself to speculation and mere theoretical explorations; however, the pictures included in the chapbook prove she did plenty of physical exploring of Shakespeare’s haunts. This edition of the chapbook, which was reprinted in 2002, is complemented not only by an intriguing (and not at all arcane) bibliography, but also by photographic illustrations of Green Men on English churches and church furniture from that part of Warwickshire and its surrounding counties in which Shakespeare grew up.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Green Man is that in Shakespeare’s day — and right through the late Victorian period — he was not much more than an architectural stop-gap, capable of being scaled down or grafted on to church architecture or furniture, as if even while being carved into wood or stone he could manifest his shape-changing magic. Yet the Green Man had an almost physical presence, “becoming part of his [Shakespeare’s] creative language later to resurface in what was to be perhaps his most popular play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream!”

Ballard makes many references to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, but it is when she is making less specific references to creativity that her prose becomes most interesting, such as in the following paragraph:

“[The Green Man] makes for a significant study not only for those of anthropological inclination but also for the student of visual arts and creative thinking — for who’s to say that the greatest creative mind in the world of English literature did not see a direct parallel to the human condition in this dualistic image representing both death and rebirth….”

Although most of the text of Ballard’s small chapbook explores the places where Shakespeare might have made his Green Man “sightings,” the more intriguing explorations are those which address the significance of the Green Man to contemporary creative artists.

(self-published, 1999)