Craig Clarke wrote this review.

Craig Clarke wrote this review.

Alexandra, Jane, and Sukie are three former wives living in the late sixties in a small Rhode Island town. They are also witches. For example, if Alexandra wants the beach to herself, a simple whipped-up thunderstorm does the trick nicely, and tennis games are made more challenging by balls that transform into frogs.

Having, with considerable overlap, worked their way sexually through all the eligible — and ineligible, which they actually prefer — men in the area, the three become very intrigued at the appearance of the man who just moved into the old Lenox mansion down the street: one Darryl Van Horne from Manhattan. (The triumvirate’s interest quickly leads to a menage a quatrein Van Horne’s humongous teak bathtub.)

A major subject in John Updike’s novels is the fallout of sex (usually adultery) and how it causes friction in otherwise smooth relationships. Thus, it’s not long before Alexandra, Jane, and Sukie are vying individually for further attention from Van Horne, to the detriment of their longterm friendship. And after a murder/suicide brings a fourth — and younger — female into the equation, tensions rise even further, especially when the new girl moves in with Van Horne.

Updike is not well-known for his sympathetic portrayals of women. His female characters are either jealous and vindictive, naive and unconditional, or are the sex objects causing those emotions in the other women. The three title characters are easily separable from one another — fully developed characters, even in short stories, are an Updike strong point — but they are scarily similar in their combined response to this conflict, using their magic for their own petty gain. To them, this girl, despite their initial instinct to mother her, is a pest equivalent to a squirrel filching from a bird feeder. As such, the reader has difficulty feeling any sympathy towards them, or towards their subsequent guilt. These are not nice women.

Updike’s prose is masterful as usual. Never plot-heavy (or, some could say, even plot-oriented), his novels are most famous for their easy pacing and their tendencies to stop in the middle of a scene and lovingly describe thoughts or surroundings. A single exchange can take pages to complete, with lines of dialogue separated by entire paragraphs. If steady attention is not paid, it is easy to lose the point of a conversation. Fortunately, however, attention is rewarded with a deeper understanding of the characters and the sense that one could walk through one of his fictional towns and know the surroundings by sight.

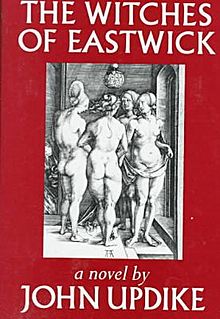

In the end, The Witches of Eastwick is a good novel. It is not a great novel; it is not even a great witch novel. The research is at best minimal and often seems negligible. Nor does it compare favorably with the rest of the Updike canon, certainly not his tetralogy of everyman Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, whose libido gets him in enough trouble to fill four novels and a novella. The book is not a waste of time, as long as the reader appreciates the abovementioned prose and description style, I’m just not sure who the target audience is. Certainly not fans of the 1987 movie adaptation, which took the basic shoestring plot of the novel and ran in a separate Hollywood direction that focused on the supernatural elements (a look at the Stepford Wives remake cited its “Witches of Eastwick-style effects”) and the actors’ personalities, Jack Nicholson especially.

As any practitioners of the magickal arts could only be offended by Updike’s portrayal of their group’s beliefs and behavior, it seems to remain that the only people who would get any satisfaction from The Witches of Eastwick are fans of the author, though even they may be turned off by the unconventional subject matter from an author whose characters usually remain rooted firmly in reality — however subjective that reality may be.

(Alfred A. Knopf, 1984; Ballantine, 1996)