I never had a chance to prove them wrong, My time was short, the story long.– Oysterband’s “The Oxford Girl”

I never had a chance to prove them wrong, My time was short, the story long.– Oysterband’s “The Oxford Girl”

So much has been written about the world of the fairies — the otherworld that we apprehend through bits of lore, heart-stopping moments of fear before the ordinary reasserts itself, direct observation in meditation or trance, dreams, and the writings of fantasy authors, folklorists or even tourism boards.

Yet for most of us at the turn of the twenty-first century, when push comes to shove we fall back on rationality. We are rational folks. When we’re feeling rebellious we may entertain thoughts of what the world would be like if the veil were thinner, if magic were real, if we could somehow touch the forces that lie under the surface of things. In that place cause and effect are more likely to occur according to the rules of sympathetic magic, oblique relationships, or symbolic affinities, and it somehow seems attractive to throw off the mundane.

Often whatever we bring back from these thought excursions turns to dust not so much because it was an illusion as because it can’t stand up to the logic that we use to negotiate the postmodern world. But what if that weren’t so? Perhaps our lives would be like the characters of any of a number of fantasy novels who encounter the spirits of place. We might find that the forces of nature were personified as people — good, bad, bitter or weary. But often what I hear from writers and mystical types is that our hope is that the otherworld somehow communicates, that we might interact somehow with the unseen forces, with the personifications of place, and that this experience would help us on our journey. But would it? This book raises another possibility as it explores how the beliefs in fairy lore embodied a collective will fearful of the forces of change.

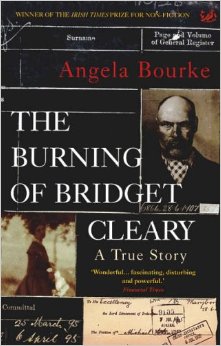

From where we sit, it’s very difficult to think of a world where the meticulous rationality is the overlay and the otherworld logic the bedrock — the belief system that makes sense in times of trouble or stress. Yet this is the world that Bourke portrays with startling insights, using everything from narratives from the trial of the nine people indicted for burning Bridget Cleary to death in her home on March 15, 1895, to weather reports and comparative social analysis. Not too many works of this sort are page-turners that get at questions dear to the hearts of mystics and others with an interest in fairly lore. But I couldn’t put The Burning of Bridget Cleary down.

Bourke allows the narrative to play out detective style, revealing layer after layer of meaning as she builds towards the horrific events of Bridget Cleary’s death in her kitchen while her father, aunt and cousins stood by. This book is a must read for everyone who believes they have had a glimpse of the otherworld — of the gentry, fairy, or other earthy spirits. It also raised some interesting questions about the view of this world presented in many fantasy novels based on folklore material. Do we really get it? Read on.

Poor Bridget’s story goes something like this. She was a stylish dressmaker with additional independent income from keeping hens, who eschewed the customary shawls and scarves of her peers for hats and cashmere jackets. Her husband was a cooper from a neighboring town who also had a good income. That, along with their childless state, had made them relatively well-off compared to their neighbors and family. The Clearys were friendly with their neighbors — an “emergency man,” or caretaker for the landlord who had moved into a farm after a family was evicted during the land wars of the early 1890s. These neighbors were shunned by a small community resentful of such opportunism. Bridget did the shopping for the them and may have been the young husband’s lover. She was out delivering some eggs and hoping to get payment owed from her uncle, and caught a cold that developed into bronchitis (pneumonia, TB?) on her two-mile trek home.

Over the next week Bridget’s condition worsened, yet the doctor, a drunk, refused to come, while the priest stayed 20 minutes and merely gave the last rites. Soon Michael Cleary and Bridget’s uncle, Jack Dunne, a seanchai well versed in herb lore, began to circulate the story that Bridget had been taken by the fairies, and the woman in the bed was a changeling. Some herbal cures were prescribed and forced down Bridget’s throat — she was also manhandled and held over the fire on Thursday, March 15, while being repeatedly asked if she was indeed Bridget or a changeling. Several family members assisted, and neighbors were present the evening before her death. Several more tests were conducted by her male relatives to see if she was truly Bridget – including throwing urine and chicken droppings on her. By the next morning, she appeared to recover, and was up, dressed and out of bed the following evening, when neighbors came at her request to verify that she was better, and not a changeling. After the neighbors left, seemingly still not convinced that she was truly his wife, Michael Cleary tried to force Bridget to eat three pieces of bread before he would give her a cup of tea — she ate two and insisted on the tea. He waved a burning stick in her face, causing her clothing to catch fire. She passed out, and he threw paraffin oil on the “changeling” and burned her to death, all the while screaming that she wasn’t his wife, that his wife would appear riding on a white horse at a ruined hill fort the following evening, when he would cut the cords that bound her with a black-handled knife. Brandishing a kitchen knife at her brothers, he forced one of them to help him carry her to a shallow grave.

The court heard this trial at the same time that Oscar Wilde’s disastrous libel case was being heard in London, and that a Home Rule bill for Ireland was being debated in the House of Commons. Bourke does a brilliant job of conveying the details of Victorian orderliness, from the recording of temperatures twice daily being sent to London from weather stations in the U.K. to the cataloguing of fairy folklore by Lady Charlotte Guest. One gets a real sense of the pervasive rationality of the era, replacing the isolation and local customs around the British empire. She conveys the ascendancy of the younger, English- speaking population of Tipperary where the Clearys and their families lived, and the waning influence and sorry economic prospects of the Clearys’ relatives. Certainly both Bridget and Michael had opportunities in the new world — indeed, they were “making it” up and out of the degradation and poverty of the rural labouring class from which they came.

So the reader is left to wonder whether Michael Cleary just cracked under the strain of his wife’s illness, falling back on an older, more ingrained belief system, or whether he manipulated Bridget’s uncle and his fairy lore hoping for leniency from the courts. Or did the old beliefs actually take over when he killed his uppity, childless wife? Or perhaps he was manipulated by Bridget’s uncle Jack Dunne — an old labourer who would never partake in the comfort afforded to the ambitious couple. Jack Dunne was a competent, bilingual storyteller whose lore was less and less valued in the new English-speaking, Victorian world. And what about her aunts, father, and cousins who stood by as she was burned to death? Was it jealousy, or their inability to confront an older relative? Bourke doesn’t provide definitive answers as she unearths facts that raise tantalizing questions in tight, well-written prose.

What becomes clear is that the fairy lore was a code, a secret language that enabled layers of meaning to be conveyed about stresses, jealousy, infidelity, and sanity under the guise of stories about the spirits of place. These stories are powerful statements of the forces over which people had no control, a projection of the animosity the land must feel — if it took so much strength to wrest a living from a hard land, the spirits of place must be resentful, if whimsical at times. Being taken by the fairies was an excuse for the appearance of the disabled child, a depressed and withdrawn spouse, or a difficult teenager. In this world, if someone was “making you a fairy” they were telling everyone to ostracize you. Banishing the changelings in the community could lead to tragic ends — as children were burned in fires to force the changeling to flee and the healthy, cooperative child to return. This book makes it clear that the stories collected by middle class antiquarians had real consequences for people encoded within the tales.

Bourke also explores some of the euphemisms subsumed under the fairy lore. I found these explorations fascinating — some interesting revelations about the Clearys’ relationship are revealed in their dialogue under the guise of fairies and changelings. Michael Cleary was living far from his family, with an uppity wife suspected of infidelity — or, at the very least, too much good luck. If this fortune were derived from trafficking with the fairy world, it cast aspersions on him. How much easier it was to blame the fairies than to address the sources of one’s resentment and oppression in a world where neighbors and family were isolated and interdependent?

After reading this book, I am convinced that many current interpreters of fairy lore only get the most surface layers — much like the middle class collectors of folklore in the nineteenth century, we often seem to misinterpret the code that was well understood by the original storytellers. How often have we read about how a work gets beyond the Victorian misconceptions of the little people, yet everything turns out all right in the end? I remain unconvinced that many readers or writers do get beyond these safe images. Our conception of the fairy world remains comfortable, often missing the horror, or the force of the collective will on nonconformists and other difficult types that made up such a big part of the phenomenon of being “taken” by the fairies. Bourke does a great job of revealing this aspect of the fairy myths — that they personified social aspects of the collective unconscious as much or more than putting a face to the natural forces beyond their control.

The Burning of Bridget Cleary is both fascinating and chilling. It is difficult to imagine being in this situation — of yelling, “give me a chance!” or “yes it’s me dada,” while being tortured by one’s family. Bourke draws the reader in by revealing multiple perspectives and alternative views of the situation, as she peels back the layers of meaning for the events and dialogue surrounding Bridget’s death. Read this book before you read your next fantasy novel — it will change your perspective on how we interact with this otherworld. If you intend to write fantasy fiction, this book will be an invaluable look into the dark side of the forces that led people to act to appease or manipulate forces embodying the collective will. And the next time you read of a quaint charm to appease the gentry, well…..

(Viking, 2000)