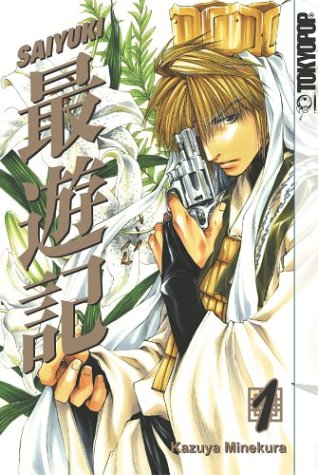

I suppose it was inevitable that, in my fascination with manga, I would eventually run across Kazuya Minekura’s Saiyuki, one of the more popular series with a decidedly “heroic fantasy” cast to it. It’s been one of the more rewarding and entertaining finds so far.

I suppose it was inevitable that, in my fascination with manga, I would eventually run across Kazuya Minekura’s Saiyuki, one of the more popular series with a decidedly “heroic fantasy” cast to it. It’s been one of the more rewarding and entertaining finds so far.

Saiyuki is an adaptation of the Chinese story “Xi-You-Ji,” or “Journey to the West.” This is a classic quest adventure with a few twists: the story takes place in a time when the world is in harmony — in fact, it is known as “Shangri-La” — and when humans and demons (youkai) have co-existed peacefully for centuries. All of a sudden, the youkai begin to go insane, attacking and eating their human neighbors and then disappearing. It seems that far to the West — in India — someone is trying to combine human science and youkai magic to free the demon lord Gyumaoh, an endeavor that is sending out waves of negative energy that are affecting the whole realm. The Sanbushutsin, the Three Aspects of Buddha, summon the high Buddhist priest Genjyo Sanzo and charge him with undertaking the journey to the West to stop this sacrilege. He will have three companions in his quest: the Monkey King Son Goku, the kappa (water sprite) Sha Gojyo, and the demon-slayer Cho Hakkai. (Ironically, Goku and Hakkai are youkai themselves, while Gojyo is a half-blood — a “child of taboo.”) They are opposed in this quest by all sorts of adversaries, both natural and supernatural, the most persistent of whom are the demon lord Kougaiji, son of Gyumaoh, and his own three companions: Lirin, his half-sister; Yaone, his apothecary, who is also an expert in poisons and explosives; and Dokugakuji, his bodyguard. The prime mover in all of this is the boddhisatva Kanzeon Bosatsu, also known as Kannon, who is, at best, a whimsical referee who has his/her own agenda. (Kannon is a hermaphrodite.)

As the notes in the first volume of this series point out, the title of Minekura’s version is written in kanji with characters that also read as “Voyage to the Extremes.” The titles in each volume render it simply as “Journey to the Max.” A hint of the attitude here may be derived from the characters themselves: Genjyo, a priest so holy he’s been entrusted with one of the Five Sutras, is fairly brutal, short-tempered, smokes, drinks, gambles, and carries a pistol — which he has no compunctions about using. Son Goku, the Monkey King, has been freed from a five-hundred-year captivity, punishment for a crime he’s forgotten, and lives mostly for his next meal and next game — mahjong or cards will do equally well — and a good fight. Gojyo has two weaknesses: good tobacco and bad women. He also carries a shakujou, a staff with a detachable, crescent-shaped head that regularly makes cutlets of his enemies. And Hakkai, seemingly an absent-minded, benign presence, uses his chi as his main weapon, always happy to try out new techniques he’s thought of, with lamentable results for his adversaries. He is also the keeper of the transforming dragon Hakuryu, which becomes, among other things, the group’s main means of transport: a Jeep.

Stylistically, the series is firmly grounded in shoujo manga (“manga for girls”): the male characters tend to be lean, muscular, and fairly androgynous, while females may be that or more voluptuous. The layouts and narrative flow are more fluid than the normally straightforward, regular frame-follows-frame arrangements common to shounen (“manga for boys”) action-adventures.

The way this story is put together is also a cut above your basic manga, and at a high level for any flavor of fiction. Minekura has made extensive and very intelligent use of flashbacks to build in backstory for the characters, especially Sanzo. It’s soon very obvious that we’re not dealing with an anti-hero here — we’re dealing with a world full of them, on both sides of the conflict. The characterizations just keep getting richer as we go along.

This is also a story built on ironies. The worldview displayed by the four main characters is in keeping with the rest of the elements: every one of them says, at one point or another, that he is out for himself. Even Goku, the irrepressible optimist, says in an encounter with Kougaiji, that he fights for himself, which gives him an edge. And the four regularly throw their philosophy aside: the squabbles reach deafening intensity, but none of the four has any hesitation about defending the others — and then trying to justify it for every reason but the real one. Even Sanzo, the prize misanthrope, after he takes a near-mortal wound protecting Goku, spends pages trying to find a way around admitting his reasons.

Another refreshing point, especially for those who are used to the black/white, good/evil dichotomy so often found in comics, is Minekura’s treatment of the opposing forces. Just as our “heroes” are far from perfect, so Kougaiji and his friends are also drawn in shades of gray: Kougaiji’s purpose is to free his mother from a spell that keeps her imprisoned; Dokugakuji and Yaone follow Kougaiji because he has saved them from unpleasant fates in the past, Lirin for simple love of her big brother. And yet there’s nothing like blind obedience here: Dokugakuji in particular has no hesitation in backing Kougaiji up against the wall. The “demon four” are mirror images of the Sanzo contingent. (Another way in which Minekura reaches through irony to humor: when the two groups confront each other, it is generally Lirin, the closest match to Goku in personality, who winds up paired off against Sanzo, and it’s usually Goku who drives Sanzo to the verge of homicide.) The real villains, Gyumaoh’s demon concubine Gyokumen Koushou, and Dr. Ni Jianyi, your basic mad scientist, and human, are almost caricatures of evil, except that Gyokumen Koushou is obviously barking mad and Ni Jianyi is completely amoral and sort of borderline himself.

This one’s a hands-down winner: it’s a marvelously complex and sophisticated vision rendered pungently and stylishly. Minekura has pulled one dirty trick here, though: the original series runs to nine volumes and only takes us halfway through the journey. Minekura has a sequel series in print, Saiyuki Reload, which continues the story, and there is a prequel, Saiyuki Gaiden, as well as the inevitable multiple anime series. I have to confess, I am completely captivated by this one — I may have to devote a whole section of my library solely to Saiyuki.

(Tokyopop, 2002-2004 [orig. Issaisha (Tokyo), 2002-2003])