I run across a fair number of musical biographies, autobiographies, reminiscences, and the like, all the way from Berlioz as seen by his contemporaries to Ned Rorem’s somewhat scandalous diaries. The common thread, of course, is that they are about musicians and ultimately, music itself. The interesting thing is the different ways they think about, talk about, and portray music.

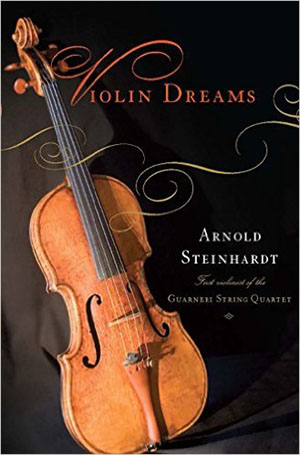

Arnold Steinhardt was for many years — since its beginnings in 1964 — the first violinist of the Guarnari String Quartet, one of the finest chamber music ensembles of the twentieth century. (In my own mind, the Guarnari has no competition except the great Budapest, its slightly older contemporary.) His tale, cast as more of a memoir, almost a collage, rather than a straightforward autobiography, gives much more than the more or less expected events of a young musician’s life. Yes, he started studying when he was six, his family loved music, he hated to practice, and just about everything else you’ve ever heard about any other gifted performer. But instead of the humdrum particulars of birth, courtship, marriage, children, and the other minutiae so beloved of biographers, we have a rich and varied tour of all that really goes into making a first-rate musician, related in anecdotes, speculations, history, and sometimes even the dreams of the title.

Arnold Steinhardt was for many years — since its beginnings in 1964 — the first violinist of the Guarnari String Quartet, one of the finest chamber music ensembles of the twentieth century. (In my own mind, the Guarnari has no competition except the great Budapest, its slightly older contemporary.) His tale, cast as more of a memoir, almost a collage, rather than a straightforward autobiography, gives much more than the more or less expected events of a young musician’s life. Yes, he started studying when he was six, his family loved music, he hated to practice, and just about everything else you’ve ever heard about any other gifted performer. But instead of the humdrum particulars of birth, courtship, marriage, children, and the other minutiae so beloved of biographers, we have a rich and varied tour of all that really goes into making a first-rate musician, related in anecdotes, speculations, history, and sometimes even the dreams of the title.

Steinhardt has for most of his career traveled with pictures inside his violin cases, images of the greats of the violin: the great nineteenth-century virtuoso, Niccolo Paganini; the equally great twentieth-century icon, Jascha Heifetz; the legendary Belgian master, Eugène Ysaÿe, the impetus for the Queen Elizabeth International Violin Competition in Brussels, in which Steinhardt took the bronze in 1963; and the great Hungarian, Josef Szigeti, with whom Steinhardt studied (with a grant from George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra, where Steinhardt was assistant concertmaster at the time — call it a signing bonus).

To be very honest, the first chapter or so did not give me the best impression. The narrative seemed somewhat disjointed and the diction is sometimes a bit florid, but I soon fell into the rhythms of Steinhardt’s story. Call it a collage, hung, so to speak, on a recurring motif, the Bach “Chaconne” from the Partita No. 2 in D. Minor. The fascination of this book is in Steinhardt’s presentation of the various episodes of his career, from his beginnings as a violin student in Los Angeles through his days at the Curtis Institute, summers at Marlboro in Vermont, his stint with Cleveland, during which time he found refuge from Szell’s somewhat dictatorial regime playing chamber music with some friends, to intimate vignettes of concerts and master classes with the likes of Yehudi Menuhin and Pablo Casals. We are also kept abreast of his growing sophistication in the matter of instruments, beginning with a mass-produced Czechoslovakian piece on loan from his school when he began his lessons, through various upgrades, including a borrowed Stradivarius and a Guarnari del Gèsu, to his treasured Storioni. He returns again and again to the “Chaconne,” a benchmark for his progress as a performer and artist, reflecting on his various approaches to true understanding of the piece as he reached new stages of maturity as a violinist. So doing, he provides for us insights what music is about, providing in his digressions and anecdotes illuminations that give a new dimension not only to appreciating the mind of the performer, but to our own understanding as the audience.

Violin dreams turned out to be, in spite of my initial misgivings, a charming and insightful adventure in the world of the musical life, high culture, and Bach. Steinhardt is, when all is said and done, a thoughtful and intuitive storyteller, and the book is terrifically rewarding. As an added bonus, the books contains a CD of two versions of the Bach Partita recorded by Steinhardt forty years apart, in 1966 and 2006. While I confess never having been particularly drawn to the piece, listening to Steinhardt, I start to get it.

(Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006)