Sarah Meador penned this review.

Sarah Meador penned this review.

Seven Wild Sisters advertises itself as a modern fairy tale. Including the seven sisters, it certainly has all the trappings: an old woman who may be a witch, an enchanted forest, a stolen princess. But Sisters is not just borrowing the clothes of fairy tale. It sings with the true voice of fairy tale: capricious, wild, and not entirely safe, but rich and enchanting.

Seven sisters — Adie, Laurel, Bess, Sarah Jane, Elsie, Ruth and Grace — get caught between two warring groups of fairies because of an act of kindness. With the help of some of the forest’s residents and one human they set out to free themselves from the trouble they’re in. Those familiar with fairy lore will recognize the rules the girls are forced to play by. The strength of promises, the power of ritual, the lore of magic numbers, are portrayed as the innate part of fairy behavior the old stories always assumed them to be. The fairies bound by these rules are properly alien, unpredictable and often dangerous. Neither the too-perfect gods of modern fantasy nor the pretty dolls of Victoriana, they defy classification, and that, of course, is what they should do.

The language of the tale, moving seamlessly between first and third person narrative, adds to its authenticity. Nothing scintillates or coruscates. Nobody spends much time thinking about their inner self or the true nature of reality. There are no fancy or false notes here, just a straightforward this-happened-that-happened presentation of the facts. This simple conversational tone, which presents a fairy attack in the same tone as a schoolgirl prank, makes the magic of the story both inescapable and acceptable.

Odd as it sounds, one of the best aspects of Seven Wild Sisters is its brevity. The real adventure in the story takes place over a couple of days, and de Lint’s compact storytelling makes it actually feel like a couple of days. The tight pacing keeps the suspense high without any forced cliffhangers. The quickness of the tale also lets the story just happen on it own, without making room for any awkward explanations of the fairy world. Exactly as much justification is given the girls’ adventure as most of us get for the plot of our lives, which is very little indeed. The determined lack of mythos creates the anytime, anywhere nature of the tale and firmly plants it in fairy and folktale territory.

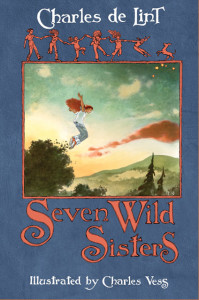

As self-sufficient as Seven Wild Sisters is, the proof I reviewed lacked a large chunk of its final self; illustrations by Charles Vess will add the last touch of enchantment to the sisters’ story. Those familiar with his work will know that it’s reason enough to buy the final book. Those who aren’t now have a wonderful reason to discover it, wrapped in the pages of a true new fairy tale.

Editor’s note: Jack just popped his head in to add his ha’penny’s worth, now that the book, in all its illustrated glory, is available:

Now, I do believe that a good book is more than merely the text within, so I will purchase a book based — at least in part — on the physical appeal of it. F’r’instance, I’ve purchased the Phillip Pullman trilogy, His Dark Materials, in the original hardcover edition because the newest edition has artwork that I find unappealing.

Seven Wild Sisters has a a full-color dustjacket as well as full-page interior illustrations and page decorations by Charles Vess, who also did the page decorations and cover art for The Green Man anthology. Charles de Lint says that he and Charles Vess have been wanting to do this for years. That’s understandable, given how cool the final product is!

Seven Wild Sisters is a slim, just over a hundred pages long, novella that I read on a very warm summer’s evening. And the art by Charles Vess certainly enhances the pleasure of reading what is already a great tale. He starts off with full-color cover art: a picture of one sister apparently flying under a freize of all of them dancing, which creates a mood of young women bursting with vim and vigor. This motif’s repeated on the inside cover — but before you look there, take off the dust jacket and look at the small fey fiddler on the book itself. Wonderful! The interior black-and-white drawings have to be seen to be fully appreciated — my favorite ones are the fey cat just after the contents page, the tree-being with a mug in his gnarly hands inside the cabin (page forty-nine), and two of the sisters watching the fey fiddler (page seventy-six). Oddly enough, this tale by a Canadian writer feels more real to me as a tale of the Appalachian Mountains than the Ballad novels written by Sharyn McCrumb, a writer born and raised there, do. I suspect that there will be more collaborations set in these Mountains between these two gentlemen!

(Subterranean Press, 2002)