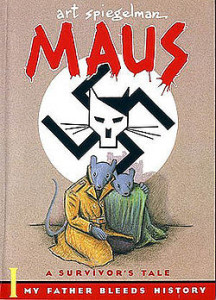

Art Spiegelman’s Maus has made a lot of waves in its 25 years. It was the first (and still the only) comic or graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize. In doing so, it brought graphica farther into the mainstream than it has ever been, and opened a lot of people’s eyes to the artform’s potential.

Art Spiegelman’s Maus has made a lot of waves in its 25 years. It was the first (and still the only) comic or graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize. In doing so, it brought graphica farther into the mainstream than it has ever been, and opened a lot of people’s eyes to the artform’s potential.

What can be said about it by now that hasn’t already been said?

Still, this was the first time I’ve read either of the two volumes that make up this historic work. So I’m sure there are others like me who know about it but haven’t read it.

Maus is the story in comic form of Spiegelman’s father’s experience of the Holocaust. The Jews in Poland are represented as mice, the Nazis as thuggish cats, the Poles as big slow pigs. It’s also the story of Spiegelman’s efforts to retrieve that story from his father. In essence, it chronicles the way in which Art Spiegelman comes to understand Vladek Spiegelman.

The Vladek we see in the present is a cranky, headstrong miser. He rarely gives a compliment, never seems optimistic. He never throws anything away, and spends his time straightening bent nails and sorting them into separate cans by their length. He picks up rubber bands and other detritus off the sidewalk and takes it home to save against some future need. When we’re first introduced to him in a flashback scene when Art is a schoolboy crying because his friends left him behind, he responds “Friends? If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week … THEN you could see what it is, friends!”

It’s a far cry from the young, carefree, debonair young man we meet in the mid-30s, first carrying on with various young ladies, then courting Anja, who becomes Artie’s mother after the war. First, though, she becomes mother to Archiev, who doesn’t survive the war.

Vol. 1 takes us to the winter of 1944, through the years when things get worse and worse for the Jews of Poland, until they are finally confined to various ghettos, and then either slaughtered or shipped off to the camps. The Spiegelmans arrive at those terrible gates of Auschwitz as this book closes.

Again, I can’t say much about Spiegelman’s writing or his art that hasn’t already been said. The writing, as in any good comic, is spare and economical — and all the more powerful for its economy — complementing the art which is midway between sparse and dense.

His subversion of the comics trope of “cat and mouse” is one of the things that make the book so powerful. In mainstream cartoons we’re accustomed to the cats as bumblers, the mice as physically weaker but always able to outsmart the Toms and Sylvesters who want to catch and eat them. Here the mice are smart and decent but weak and dithering, always overmatched by the numbers and cruelty of the burly, uniformed, armed cats. The mice like Vladek who have the right combination of cleverness and luck somehow survive to tell the tale, but they are irreparably damaged, and as we see from hints about Art’s life, that damage extends to future generations.

Pantheon, 1986