Utawarerumono is the title of an anime series from Japanese TV that has made its way to North America on DVD, and it’s — well, it’s somewhere in the realm of historical romance cum science fiction future history. If you know what I mean. Hint: the title Utawarerumono translates as “He Whose Song Is Sung” — we are clearly dealing with a legend in the making.

Utawarerumono is the title of an anime series from Japanese TV that has made its way to North America on DVD, and it’s — well, it’s somewhere in the realm of historical romance cum science fiction future history. If you know what I mean. Hint: the title Utawarerumono translates as “He Whose Song Is Sung” — we are clearly dealing with a legend in the making.

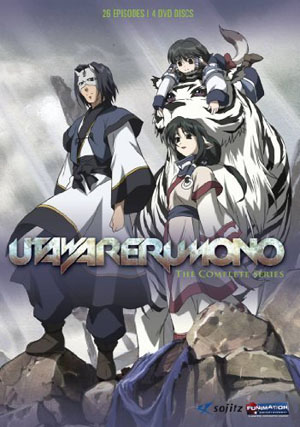

A severely wounded man wearing a half-mask is found in the woods near the village of Yamayura by a young woman, Eluluu, granddaughter of the village healer and chief, Tuskuru. They nurse him back to health, and Tuskuru names him “Hakuoro,” after her late son — he has no memories of his past, no idea of his name or who he is, and he can’t even see his whole face — the mask won’t come off. His quiet, benign nature soon earns him a place in the community, especially after he figures out how to defeat the Master of the Forest, the Mutakapi, a great, seemingly invulnerable white tiger. When Tuskuru is killed defending her other granddaughter, Aruruu, from one of the local baron’s soldiers, the villagers choose Hakuoro as their leader. They also decide that the death of Tuskuru must be paid for, and the path to empire is set.

I called it a “historical romance,” and it truly is: the tenor of the entire series is very much in the romantic mode, alternating triumphs and tragedies, battle scenes punctuated with small vignettes of domestic tranquility. One of the most appealing aspects of this anime is that the characters, whatever their antecedents, are very human — except for some of the villains, who teeter on the edge of caricature and sometimes fall over. Indeed, by the time we get to the first bad guy who is seriously evil rather than just arrogant and stupid, we’re a little beyond the realm of the believable. Except, for the observant, there is another force at play here, one that, all unbeknown to Hakuoro, is his sworn enemy.

However, that relationship, as we slowly discover, is not all that simple. That’s another part of the appeal here: we discover things as the story goes on that serve to illuminate not only the events happening in the “now” but the history. It’s not until fairly late, for example, that we learn that this story takes place in a far future in which humans are not able to live on the surface of the earth. That’s when we learn why everyone except Hakuoro has cute furry animal ears, and some have wings. (Women also have tails, and it’s grossly impolite to touch a woman’s tail without her permission. Take that as you will.) In the same way, the presence of Hakuoro’s enemy, and not only his true nature but Hakuoro’s, is revealed slowly.

This is all part of the second half of the series, although the seeds are sown early on. The first half is a fairly straightforward epic of conquest (which is not really what Hakuoro wants, but the neighbors just won’t leave him alone), as Hakuoro surrounds himself with a group of mighty and somewhat eccentric heroes — Oboro, the harum-scarum bandit whose sister is terminally ill; Karurua, the former slave girl who wields a sword no one else can lift; Benawi, the general whom Hakuoro defeated and his trusty lieutenant, Kurou; and the cub of the Mutakapi, Mukkuru, a a fearsome beast in his own right, whom only Aruruu seems able to control. And not all of these people are what they seem, any more than Hakuoro himself is. They are all vividly drawn, not only the heroes but the children (and yes, there are children — Aruruu is only one of a trio of girls who are enough to terrorize any doting father or brother) and the secondary characters as well.

The animation is well handled, if not spectacularly so, the CGI effects blending in almost seamlessly. (Particularly entertaining are the long-shots showing the wopters, the bipedal dinosaurs that everyone rides, marching off to war: it’s like a flock of starlings on parade.) Character designs, interestingly enough, fall into two categories: the major characters are all what I call “shoujo standard,” with elfin features, large, dominant eyes, and small mouths and noses. The secondary characters, however, display a full range from barely stylized realism to grotesque. Somehow, it all works.

If it weren’t for the bloody battle scenes, I would have no trouble recommending Utawarerumono as family entertainment: there’s a lot of humor in this one, low-key as well as near-slapstick, and many scenes that display a kind of innocence that is all too rare in anything these days — and they do manage to avoid the saccharine, thanks largely, I think, to Hakuoro’s often bemused reactions to some of the goings on. (And it’s to the animators’ credit that a face covered in a half-mask can be so expressive.) Within my admittedly limited experience with anime, it’s not in the top rank, but it has an elusive appeal that keeps one coming back to it.

(Aqua Plus, Oriental Light and Magic, 2006)