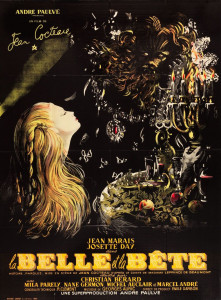

Jean Cocteau’s sumptuous black and white retelling of this beloved fairy tale is inarguably the finest version committed to celluloid. Drawing heavily from Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s 18th century written version, Cocteau wrote La Belle et la Bete’s story and dialogue, as well as directing.

Jean Cocteau’s sumptuous black and white retelling of this beloved fairy tale is inarguably the finest version committed to celluloid. Drawing heavily from Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s 18th century written version, Cocteau wrote La Belle et la Bete’s story and dialogue, as well as directing.

The story should be a familiar one to all. A merchant, fallen on hard times, lives with his children in the country, awaiting the day when their fortunes will turn and they can return to town in style. As luck has it, one of the merchant’s ships eventually comes safely ashore, bearing goods. Before leaving for town, he asks his daughter what they want him to bring back with him. While her vain and selfish sisters ask for jewels and clothes, Beauty asks only for a solitary rose, little knowing how this simple request will affect her family. And so the merchant sets off. Only to discover his creditors have seized his goods as payment before he can claim them. Distraught, he heads back home, only to get lost in a great forest.

Taking shelter in an odd, frightening, yet beckoning castle, the merchant passes the night without seeing a soul. But on his way out the next morning, he pauses to take a rose for Beauty from the beautiful garden, summoning the angry Beast, who demands the man’s death, or that of one of his daughters. The terrified man agrees to send a daughter in his stead (with no intent of doing so) and flees home to the vitriol of his eldest daughters, and the steely determination of Beauty, who sees what must be done. Beauty returns in her father’s stead, and remains with the Beast, learning of the gentle, sweet being beneath his rough exterior — and nightly refusing his proposal of marriage.

Cocteau made a few changes to the story (losing a few siblings, adding a mundane love interest), but kept most of Beaumont’s version intact. He chose simple, sincere dialogue to tell the story, as if understanding that what would make his version so distinctive, so special, wasn’t witty or meaningful words, but imagery and atmosphere.

And what atmosphere. Cocteau makes remarkable use of light and shadows, texture, and literally human architecture. The Beast’s castle is otherworldly, cold stone cast in shadows from flickering candles in gilt candelabra held by human arms jutting from the walls. Human statuary flank the dining room fireplace, their eyes shifting to take in the scene before them. An arm rises from the table to serve Beauty or her father. Simple effects put to stunning use with paint and lighting.

Other wonderful touches abound in the movie. Consider Beauty’s dress as it changes from peasantry plain to royal luxury when the Beast carries her into her bedroom. Watch how Beauty flows from a wall, or emerges from the downy depths of her bed at home as she magically moves between the castle and her father’s house. Simple production techniques by today’s standards, but amazing for post-World War II France. And still amazing to watch.

Beauty’s first visit to the Beast’s castle is sublime, an exquisite scene worth watching repeatedly. Clad in a long flowing gown, she hurries fearfully into the castle’s hallway. The eerie candelabra light up one by one as she passes, their glow rippling across the cloth of her dress, bringing it to life. She ascends to the second floor, discovering a hallway of open windows, their curtains blown inwards by a brisk breeze. Beauty floats down the hallway, an ethereal angel kissed by clouds of sheer gauze. It is a stunning, gorgeous moment in time. Achieved, apparently, by pulling the actress down the hall on a dolly.

The entire movie is suffused with similar moments and touches: A statue coming to life to protect the Beast’s possessions. Beauty’s magic mirror. A fur comforter beckoning Beauty to bed. A priceless necklace turning to vines and back, in an instant. All subtle, but masterful.

Josette Day is positively luminous as Beauty. True to the character’s name, she is quite lovely, radiating a gentle, steely resolve as she tries to be good, noble and self-sacrificing. Jean Marais does a fine turn in triple roles: Avenant (the love interest), the Beast and the Prince. He shines brightest as the Beast, his voice, made raspy through manipulation, conveys wonderfully the Beast’s anger, frustration and sorrow.

The charisma of the main actors, combined with Cocteau’s production witchery, bring this classic tale to life in a way that can never be reproduced. Not with animation. Not with computers. Not with big name stars. This version has heart — a very strong, palpitating one. And may it continue beating for generations of movie watchers to come.

(DisCina, 1946)