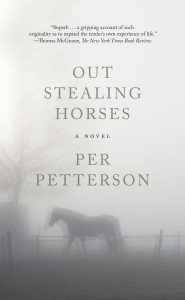

During a recent convalescence when I couldn’t get to the library I decided to re-read an old favorite. As with any truly good book, Per Petterson’s Out Stealing Horses handsomely rewards a second reading. It had been high on my list of favorite books of the 2000s, and now it might be even higher.

During a recent convalescence when I couldn’t get to the library I decided to re-read an old favorite. As with any truly good book, Per Petterson’s Out Stealing Horses handsomely rewards a second reading. It had been high on my list of favorite books of the 2000s, and now it might be even higher.

A bildungsroman set in rural Norway just three years after that country’s Nazi occupation ended with the War, the story is told in first person by Trond Sander. The narrative is split between late 1940s Trond and present-day (1999) Trond; he’s now in his 60s, retired, and setting up bachelor quarters in a remote cabin by a lake with only a dog for companionship. The surroundings and an encounter with a neighbor send his thoughts to things that happened in his youth that he apparently has not revisited in a half-century. In this remembered part of the narrative he is 15 years old and spending a second post-War summer with his father at a cabin by a river, a long day’s journey by rail and on foot from their home in Oslo. These summers are mostly a lark for Trond, a break from the somber city, his somber mother and his bothersome sister. He hunts and fishes and roams the forest, sometimes alone but increasingly with a local boy named Jon.

Adult Trond’s reminiscences and dreams circle around a particular day and the changes its events set in motion for young Trond. He and Jon go out joy-riding on a neighbor’s horses and Trond gets thrown but not badly injured. Then Jon does something that shocks and puzzles Trond, who only later finds out that the previous day when the two were out gallivanting around, a horrible accident took place at Jon’s home, for which he was responsible through negligence. The reverberations of that occurrence slowly pull back the curtains from Trond’s eyes and he begins to see the hidden subtext all around him in the actions of his father and other adults in the village.

At its most basic Out Stealing Horses is a story of war-induced trauma and its generational effects on society, families and individuals. Petterson is a highly skilled writer, and the translation by Anne Born captures the story’s nuances quite well. Petterson’s spare prose style perfectly matches Trond’s dry, buttoned-up personality and the difficulties he has in coping with unfamiliar emotions and situations. The author employs all kinds of skillful foreshadowing, as well as metaphor and symbolism of things covered up or hidden, light emerging from darkness. Not every writer can tell a tale from the viewpoint of a child or adolescent in a way that tips off the reader as to what is happening behind the scenes but which the protagonist does not understand. At several junctures, young Trond says, in effect, “something was going on here, but I didn’t know what.” Only slowly do the puzzle pieces begin to fall into place for both Trond and the reader, and it’s quite late before we learn what has driven adult Trond back out into the forest to live out his retirement as a hermit.

If you’ve never read this little gem, I highly recommend it, and if you have read it but it’s been a while, consider taking another look at it. It’s a short novel at just over 250 pages, but don’t expect to breeze through it. Out Stealing Horses rewards — perhaps even enforces — a slow, contemplative approach.

(Graywolf Press, 2003)