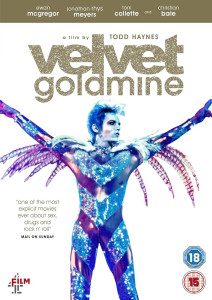

I have seen Velvet Goldmine three times, and the last time I watched it, I asked if I could review it for GMR. When the two vintage Bowie CDs were thrown in, they swallowed the bait whole. So, out came the 30-year-old LPs and closet-Glam memories. There. Now you know I’m old. Oh well.

I have seen Velvet Goldmine three times, and the last time I watched it, I asked if I could review it for GMR. When the two vintage Bowie CDs were thrown in, they swallowed the bait whole. So, out came the 30-year-old LPs and closet-Glam memories. There. Now you know I’m old. Oh well.

It would cost me thousands of dollars to replace my entire record collection with CDs, and by that time, CDs would be obsolete, too. But because of this review, I did replace several of my Bowies and T. Rexes, and hey, why not add the soundtrack to Velvet Goldmine? I have found myself staring at my Roxy Music and Lou Reed LPs like a vampire stalking victims. And it’s all Velvet Goldmine‘s fault. If Goldmine is a Valentine for Glam Rock, this chocolate’s a sweet one. And it’s as powerful an evocation of the ’70s as any genie could produce.

I was much younger than Goldmine‘s Arthur (Christian Bale) when Glam appeared at the beginning of that decade. I was a cheeky little kid in an all-girl’s Catholic school in a small town in the American Northeast, which was so far from British music perspective that even laser surgery couldn’t correct the vision loss. In eighth grade I had discovered Bowie’s Space Oddity, and in the ninth grade, my new best friend (she was in high school!) had a hip friend “Susan G” (names changed to protect the guilty) who was into Glam.

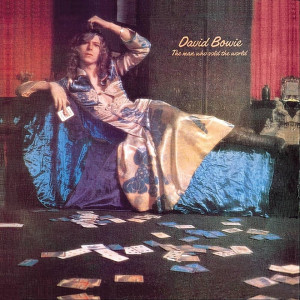

Huddled around the stereo set in Melanie’s bedroom, I fell in love with Marc Bolan and T. Rex. While Melanie’s mother baked chocolate chip cookies, we were sniggering over the naughty British boy’s lyrics. “Bleached on the beach, I want to tickle your peach…Terraplane Tommy wants to bang your gong…” Juicy stuff, that. Melanie owned the T. Rex albums Electric Warrior and Slider. She had glitter eye makeup she was capable of sharing. But while I had (and may still have) this huge crush on Marc Bolan, it was The Man Who Sold the World who sold me.

The Man Who Sold the World is David Bowie’s second commercial release. It differs from his first delivery Space Oddity in that way which was to become Bowie’s signature chameleon trick, evolving different personas and morphing musical styles like other people changed clothes. Where Oddity is a kind of acoustic cosmic folk, The Man Who Sold the World is soaring electric phantasmagoria. Much of this kick comes from the explosive power of Mick Ronson on lead guitar (yes, I have an autographed photo of him). The album liner notes say this about the recording: “Neither metaphor nor analogue, Bowie’s music insists on its own reality … this album, recorded at the onset of the decade, is a clear prognosis for the ’70s.”

The Man Who Sold the World is David Bowie’s second commercial release. It differs from his first delivery Space Oddity in that way which was to become Bowie’s signature chameleon trick, evolving different personas and morphing musical styles like other people changed clothes. Where Oddity is a kind of acoustic cosmic folk, The Man Who Sold the World is soaring electric phantasmagoria. Much of this kick comes from the explosive power of Mick Ronson on lead guitar (yes, I have an autographed photo of him). The album liner notes say this about the recording: “Neither metaphor nor analogue, Bowie’s music insists on its own reality … this album, recorded at the onset of the decade, is a clear prognosis for the ’70s.”

The Man Who Sold the World has actually been released with four different record jackets, including one of Bowie dressed as a courtesan in a long dress. In whichever jacket the listener ended up with, however, they receive a ticket into David Bowie’s wriggling psyche. The centerpiece of the recording is, of course, the eight-minute classic, “Width of a Circle.” Throbbing and pulsing with forbidden fruit, “Circle” is a surreal masterpiece. In it, Bowie boldly confesses his bi-sexuality: “I cried for all the others till the day was nearly through/For I realized that God’s a young man, too.” During a seduction segue by a male “demon” lover, thumping with tribal drums, David decides: “And the moral of this magic spell/Negotiates my hide/When God did take my logic for a ride.” But The Man Who Sold the World is much more than “Width of a Circle.” “Running Gun Blues,” “The Man Who Sold the World,” and “Savior Machine” electrically weave elements of sci-fi into the surreal mix. “All the Madmen” haunts, and the “Supermen” calls us out into the mist of an ancient monolith. The entire album is a bold step forward into the Glam Scene. David Bowie may not have been the first there, but he became both its god and its goddess.

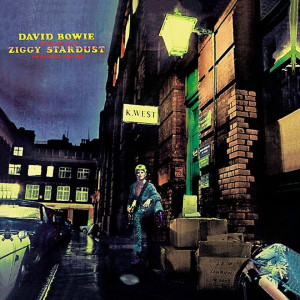

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, released in 1972, reveals a point of amazing maturation in music and style. Bowie is reaching for stardom not only with both hands, but with the confidence of a real rock star. Ziggy is full of Bowie’s readiness and ability to fill that role. In “Star” he says: “I’d send my photograph to my honey, and I’d come on like a regular superstar.” In “Lady Stardust,” Bowie introduces his rock alter-ego, Ziggy: “People stared at the makeup on his face/Laughed at his long black hair, his animal grace”. But by the end of “Ziggy’s” set, everyone is straining to listen, and hard. The recording fulfilled its maker’s audience: they, too, were listening hard.

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, released in 1972, reveals a point of amazing maturation in music and style. Bowie is reaching for stardom not only with both hands, but with the confidence of a real rock star. Ziggy is full of Bowie’s readiness and ability to fill that role. In “Star” he says: “I’d send my photograph to my honey, and I’d come on like a regular superstar.” In “Lady Stardust,” Bowie introduces his rock alter-ego, Ziggy: “People stared at the makeup on his face/Laughed at his long black hair, his animal grace”. But by the end of “Ziggy’s” set, everyone is straining to listen, and hard. The recording fulfilled its maker’s audience: they, too, were listening hard.

Velvet Goldmine‘s “Maxwell Demon” character (Brian Slade’s rock alter-ego), mirrors a certain paranoia Bowie made no secret of at this point in his career: the fear that he would be assassinated on stage by crazed fans. In Ziggy, the fantasy plays out. Bowie sings: “When the kids had killed the man, I had to break up the band.” This is the very point where the film Velvet Goldmine picks up.

The film is a terrific magnifying glass under which to examine the Glam era, thanks to writer and director Todd Haynes. In the beginning of the film, “Maxwell Demon” is killed at the peak of his career, onstage, to the horror of his fans. But the “killing” is really a publicity stunt that goes terribly wrong. Brian Slade (Jonathan Rhys-Meyers) disappears from public sight. Fast-forward 10 years and Arthur, a British journalist who actually attended the fateful concert, is called upon to find out whatever became of Slade. Understandably, the story is much more than a job to Arthur, involving as it does many unresolved emotions in his own life.

Now, Rhys-Meyers may or may not be portraying David Bowie, Ewan MacGregor may or may not be portraying Iggy Pop in his Curt Wild character; Micko Westmoreland may or may not be playing Lou Reed in his Jack Fairy. It doesn’t really matter. The Glam landslide touched off a huge movement in Britain — and especially London — among young people to imitate and flaunt their own dramatic poses, including bi-sexuality. In a BBC “interview” chronicling this phenomenon at the beginning of Goldmine, one boy says: “Yeah, I like girls. I like boys. It’s all the same, isn’t it?” Haynes weaves his own premise into Goldmine — particularly in the youthful scenes of Slade, Wild, and Fairy (which are such a hoot) — that Glam’s roots lay in the underground gay and cinematic culture, emphasizing fantasy and drama. On the Glam scene, one had to be terribly reckless and wild, and possess a dangerous openness. Though Glam was a short-lived “culture,” it opened up important identity questions of sexuality, and proposed a dramatic ambiguity.

As any perfect fantasy — urban or otherwise — should, Goldmine begins with “Once upon a time…” Oscar Wilde is left, as a baby, possibly by extraterrestials — on a family’s doorstep. Flash forward to Wilde in a nineteenth-century school room, earnestly declaring, “I want to be a pop star.” This is Hayne’s most supremely adept perceptions: Velvet Goldmine seems to carry out Oscar Wilde’s wittiest and kinkiest kicks, and Wilde has no doubt been giggling with glee in his coffin. In fact, Jim Haynes himself says: “Glam Rock seems a direct application of what Wilde was trying to do in literature — to kick the pants off the romantic tradition that preceded him … he knew to tell the truth only through the most exquisite lies.”

That said, Velvet Goldmine allows its story to unwind as one long, delicious fantasy. The story’s vehicle is a mystery, bringing characters together over a death — or in this case, the fictional death of cosmic rock star Brian Slade. Brian’s character is unfolded through a series of vivid remembrances, first through his ex-manager, Cecil (Michael Feast), then Brian’s ex-wife, Mandy (Toni Collette), and finally, ex-lover, Curt Wild (Ewan McGregor). The presentation is this film’s biggest delight. A masterpiece of imagination, Goldmine offers a colorful and awesome array of visions and fantasies. The soundtrack, (by various artists) is not only outstanding, it’s an integral part of the film. For Velvet Goldmine is really a collection of fantasies and characters set to music.

The film’s characters are outrageous and fascinating. The dialogue is sassy and cheeky. Though all the players are dynamite, the great favorite has to be McGregor’s Curt Wild. Watching Ewan thrash nude onstage, then play out his hysterical role as a stoned June Cleaver bringing Brian Slade cocktails and slippers as part of their manager Jerry’s (Eddie Izzard) publicity hype, is just too much fun. But, as ex-wife Mandy notes ruefully, “the idea” of such a coupling never demands reality. In fact, when “the idea” merges with “the actuality” anywhere in this film, especially within any of the multiple poses adopted by each character — disillusionment follows. Identities are questioned and re-invented at every turn.

In his investigation, Arthur not only dredges up all of the ingredients to the mystery of “Whatever Happened to Brian Slade”; he struggles to resolve the identity issues within himself. In one scene, young Arthur is caught jerking off to a “nude” picture of Brian Slade on an album, and disgusts his parents. He is used to sneaking out of the house dressed primly, and hiding his glittery shirts, earrings, and makeup under the stairs. Arthur is only one of those who has dreams at stake, as his past—and his destiny—are bound up inextricably with Brian Slade and Curt Wild’s.

Who cares if, when he does find out what has happened to Brian, the suit-and-tie powers-that-be are no longer interested? Arthur has reached a personal turning-point. Is Curt Wild’s presence in his life coincidence — or a fantasy? Delightfully hard to tell in a film whose reality IS fantasy.

As for me, do I care if these CD’s are 30 years old, and if Velvet Goldmine betrays my age? I haven’t had this much fun in a long time. Bowie’s The Man Who Sold the World and Ziggy Stardust have more than stood the test of time, and David Bowie — unlike Brian Slade — is still around, and still wonderful (if more subdued). And the surreal memories of the characters in Velvet Goldmine belong, partly, to me, too. I remember a certain ninth-grader with a self-inflicted Ziggy haircut and glittery satin tops. If you must know, I found the Glitter guys beautiful. I still love the androgynous imagery. Why can’t a man be beautiful? But uh, no, I never jerked off (even if I could) to the airbrushed “nude” Bowie photo in Aladdin Sane that Velvet Goldmine “borrows.” The whole Glam scene certainly may have been social “suicide” — at least in my school, where the other kids were listening to Lynyrd Skynyrd and Earth, Wind & Fire — but I’m reminded of the lyrics in the last song on Ziggy Stardust, “Rock n Roll Suicide”: “Oh no, love, you’re not alone, no matter what or who you’ve been…”

I think Ziggy’s speaking to the Glitter Kids. I’ve seen Velvet Goldmine three times, so I know Mr. Bowie’s words are true. I can smile. I’m NOT alone.

Do I recommend this dishy threesome? Absolutely! Buy the CDs if you don’t already have them, see the film —dress up, create a life, tell outrageous lies. Paint yourself a fantasy. The dream doesn’t have to be over.

(Miramax, 1998)

(EMI, 1972)

(RCA, 1971)