Jessica Paige wrote this for Folk Tales.

Jessica Paige wrote this for Folk Tales.

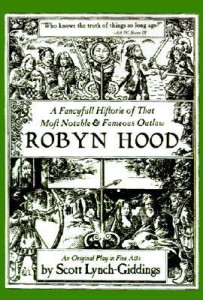

A Fancyfull Historie of That Most Notable & Fameous Outlaw Robyn Hood doesn’t wait until you’re done gasping for breath from saying the title to let you know what you’re in store for: a good old-fashioned romp through the life and times of “that most notable & fameous outlaw” Robin Hood.

But don’t worry. Scott Lynch-Giddings doesn’t give us “just” another Robin. He gives us a play with deliciously Elizabethan language (the interesting, well-researched foot notes come in handy!), amusing tongue-in-cheek repartee, and all of the old hall-marks of our favorite tale. As a read, it was fun. As a performance, it would be better. [Maybe not. -Ed.] After sitting down to read the first scene, I didn’t think that Robyn Hood would be able to hold my attention or my interest. After all, it had been advertised as the play Shakespeare never wrote — and I could see why he hadn’t written it!

Imagine my surprise when an hour later I realized that I was reading the last scene of Act Four and my name had been shouted four times before I came out of Sherwood for dinner.

But there are still a few flies in the ointment. In the end, Robyn Hood is good and not much more. While the secondary characters (Friar Tuck, Will Scarlock, Friar Tuck, Much the Miller’s Boy, Friar Tuck, Sir Robert de la Lee, did I say Friar Tuck?) are unforgettable, the same can’t be said about Robyn and Marian. Their love scenes (there are love scenes?) are flat, and I kept wondering why I wanted to skip past their parts and on to something more interesting.

That’s when it hit: “I know! They have no soul!” And they don’t have much of one. At least, not in the reading. This is just another reason the play will be more enjoyable as a play. Robyn and Marian have a spark of potential, but the spark fails to catch flame, and watching characters almost live but not quite manage it is sad.

However, the good points outweigh that flaw: a few surprising twists, Elizabethan language that really makes you believe that A Fancyfull Historie is a superior treatment of the Robin Hood myth (though maybe not quite as good as Shakespeare himself), interesting characters, banter, lewd Renaissance songs . . . what more could you ask for?

If you happen to be a Robin Hood buff, the list of references in the back of the book will have you drooling. And maybe the Afterword, with commentary on why Shakespeare probably didn’t write about Robin Hood, and the speculation and history surrounding Robin’s existence, amongst other goodies.

Final analysis? Fun, light-hearted, authentic. An impressed golf-clap for writer Scott Lynch-Giddings’ use of language, and the depth of his research. It might not be the first thing I rush out to see when it hits theaters near me, but it won’t be the last.

(Writers Club Press, 2001)