Lenora Rose wrote this review.

Lenora Rose wrote this review.

The premise of Pleasantville is fairly straightforward. Teenage twins David and Jennifer are magically transported into the actual black and white world of the TV show Pleasantville, taking the place of TV twins Bud and Mary-Sue. David, a rabid fan of fifties sitcoms and nostalgia programming, is at first reluctant to change anything in this new world, but soon gets propelled into leadership. Jennifer, obsessed with popularity, clear skin, and sex with top jocks, forges ahead in an attempt to find, or make, something here she can actually stand. Culture clash ensues between the real world 1990s and the television world where fire does not burn, and where the roads loop back on themselves. This clash is accompanied by an astonishing amount of sex behind the scenes, teenage rebellion, a sudden flourish of the arts, and the black and white world turns colour a bit at a time.

The theme of the piece is change – not progress, which suggests all change is for the better, all innovation immediately positive. Indeed, along with sex, art, and literature, there is prejudice and rioting. Rather, it puts forth a simple concept: the world changes, for good and ill, and people change with it – or against it. It most definitely takes the side of those people who work to embrace change, or at the least to accept it and face it unafraid. It opens by pointing out a lot of negatives in our current world – but soon enough hints that there are problems if the fantasies we use to escape are too unreal. In the end, the best world seems to be one that balances both our supposed ideals and the real world, warts and all. It also challenges the concept that anything is ever “meant to be,” since fate doesn’t allow for change.

The film also promotes the arts – all arts – as an essential part of a healthy society. Paintings and literature are relevant to the plot, and music is used to better-than-usual effect, particularly early rock n’ roll, with its associations with teenage rebellion. And, of course, the film itself is an obvious tribute to cinema. Both the premise and the particular attention to the arts demand a close attention to visual detail, and the cinematography does deliver. The film is packed with visual references to early films, from the young man standing, arms flung up, in the rain, to the slow drive to lover’s lane amidst tumbling rosy blossoms. The colour tinting is glorious, and the film is not afraid to linger just a little over odd details, a welcome change in the midst of the modern flash imagery.

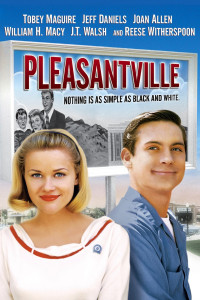

The performances are crisp throughout, but particularly among the stars. Reese Witherspoon is at first too shrill in both voice and performance, as Jennifer, the flirtatious and popular one. But she settles into her role nicely, the performance maturing as the character does. Tobey Maguire shines, from his first appearance, timidly asking out a girl who is standing far too far away to hear him (a scene oddly echoed in his later role in Spiderman), to the self-confident and reassuring leader at the end. The best performance of the film, however, goes to Joan Allen. The character of Betty changes from ever-smiling virgin housewife through the confusion and fear of awakening sexuality to become a strong and serene woman. It could have been a limp mockery, “puberty at 40,” but Joan Allen infuses her role with a dignity and spirit that makes her the most sympathetic character. William H. Macy struggles with a part that is too close to caricature, as George, the father who is the most resistant to change, lost in the new world coming to life around him.

The film has been criticised for using sex, sex, and yet more sex as the vehicle for change, as if it were endorsing teenagers to have unprotected and heedless sex whether or not they’re ready. And there is some validity to this. After all, the beginning of the mostly positive transformation of Pleasantville is Jennifer’s seduction of Skip Martin, the basketball champion.

Or is it? The characters in Pleasantville show that they, personally have changed, when they begin to turn to colour – be it gradually or instantly. Yet, while Pleasantville itself changes when Jennifer introduces sex, and changes more when Skip tells the other basketball players about the event, Skip himself doesn’t change colour for some time; nor do others whose actions prove they have discovered their sex drive.

And more, the first change comes from David, the one who at first loves Pleasantville as it is. But he loves it because he sees the characters as people, with all the attendant thoughts and feelings. Instead, he discovers, they are characters – automatons going through their roles at the dictates of the show. When David comes in late to his job at the soda shop, soda jerk Bill Johnson is still wiping the counter as per the script – but he has been frozen in place, wiping it for so long he has worn the enamel away. Immediately, David introduces the concept of choice, of free will – and by a handful of words, sets the whole ball rolling to turn the town upside down and inside-out. There are more and other subtle hints that the sexual awakening of the teens – and later, the adults – is only a veneer, a surface change that disguises a deeper transformation. Eventually, this undercurrent surfaces, as Jennifer observes that having sex hasn’t made her change to colour – but discovering other, previously unknown joys does. But of course, if the serious side were to come out too soon, there’s less room for the absurdity of the two worlds colliding.

In fact, the biggest weakness of the film is just that: the clash between the humour and the central theme. This is, after all, a comedy, so several scenes push for humorous twists that hide, or sometimes outright contradict, the deeper point.

Yet overall this movie is an excellent and layered film, which can be appreciated as a lighthearted (and relatively tame) sex comedy, as a nod to the role of the arts in society and social change, or as a deeper, more thoughtful study of fantasy and transformation.

(New Line Cinema, 1998)