Jay Farrar has put out a record that is a worthy successor to his band Son Volt’s 1995 debut, Trace. Okemah and the Melody of Riot is a masterpiece that reflects – somberly, angrily and joyfully – on the current state of the United States and its people, five years into the new millennium.

Jay Farrar has put out a record that is a worthy successor to his band Son Volt’s 1995 debut, Trace. Okemah and the Melody of Riot is a masterpiece that reflects – somberly, angrily and joyfully – on the current state of the United States and its people, five years into the new millennium.

Farrar, Jeff Tweedy and Mike Heidorn formed Uncle Tupelo in a small southern-Illinois town in the late 1980s, and their country-punk debut No Depression was a shot across the bow of independent music. The genre that Uncle Tupelo typified came to be known as alt-country, and for some Farrar’s Son Volt and Tweedy’s Wilco continue to be its flag-bearers, though the two apparently haven’t spoken since Uncle Tupelo broke up in 1994 after only four albums.

Farrar’s craft at its best, solo or with Son Volt, has married his introspective and poetic lyrics with tuneful, riff-laden music that combines the down-home of country and the jagged anger of punk. Even though he’s from much farther south in the heartland than they, Farrar is inevitably influenced by those two other poets of the prairie, Bob Dylan and Neil Young. But his touchstones are more “Tom Thumb’s Blues” than “Blowin’ in the Wind,” more “Ride My Llama” than “Heart of Gold.” And he is nearly as adept as either of those gentlemen at metaphor, using sparse and sometimes cryptic lyrics to paint detailed pictures of ordinary people and places that reflect the currents that ripple through American culture.

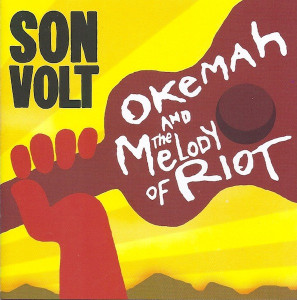

And that’s exactly what he does on Okemah. Here are images of and references to the panoply of U.S. history in the past half-century. The title itself is a reference to Woody Guthrie’s Oklahoma hometown, and Farrar sings in the opening track, “Bandages and Scars,” of “the words of Woody Guthrie ringing in my head.” The album’s cover art itself eloquently speaks of disparate currents in American music. The poster-like graphic of a guitar being held aloft in a fist’s tight grip calls to mind both Guthrie’s own instrument, with its legend “This machine kills fascists,” and the original posters for Woodstock, with its peaceful dove perched on the guitar’s neck. Elsewhere, he travels down Highway 61 with Dylan and Leadbelly, meditates on the shock waves of Sept. 11, 2001, sings the praises of American music, and angrily indicts America’s leaders for bellicose posturing and fomenting a seemingly endless “war on terror.”

It’s the type of thing Farrar has always aimed for but rarely achieved quite so well. The secret is in the music of Okemah itself, which is catchy and immediate, sometimes tuneful, sometimes raw but always engaging. Part of the credit may go to the fact that this is a new band under the Son Volt name, and part surely goes to the stripped-down recording process; whatever the reasons, this music sounds fresh and vital compared to the sometimes turgid and cerebral feel of much of Farrar’s post-Trace output. This music is fun to listen to.

After setting the stage with the ruminative opener, “Bandages and Scars,” the rocking “Afterglow 61” combines wailing Neil Young-like riffage from guitarist Brad Rice with a catchy melody and a sing-along chorus: “There’s no reason to feel downhearted/there’s music in the wheels there to be found.” On this and most of the songs on Okemah, Farrar sings in the upper range of his baritone voice, and he demonstrates impressive control on glissandos here and elsewhere. Other feel-good rockers include the classic Son Volt-sounding “Six-String Belief”; “Gramophone,” another one with a sing-along chorus and some soulful B-3 organ and wailing blues harp; the rocking “Who,” with its Byrdsian jangle; and “Chaos Streams,” whose stop-start rhythm and staccato electric guitar harken back to Uncle Tupelo’s sound.

Farrar also is his angriest and most directly political since early Tupelo records. The post-punk squall of “Jet Pilot”‘s refrain – “The revolution/will be televised/across living rooms/and the Great Divide” – is punctuated by the sing-song satrical verses aimed at hypocritical politicians, particularly one currently in the White House. And “Endless War” is a bitter indictment of a society that wastes the young lives of its working classes in an ill-defined worldwide conflict. Upbeat musically, the song asks a lot of depressing questions: “Brought up in the neighborhood without dreams … Still trying to understand how another wrong makes a right.”

The rockers are intercut with slower pieces, like “Atmosphere,” a meditation on Sept. 11, 2001 and its aftermath, with slow and fast sections alternating; the cryptic but pretty love song “Ipecac;” and the eastern-tinged “Medication,” colored by a slide dulcimer, droning bass and shakers. This song contains more of Farrar’s typically impressionistic lyrics that evoke images of environmental degradation and psychic emptiness.

The album ends with two versions of another song that is both love song and metaphor, the waltz-time “World Waits For You.” In the first, it’s just Farrar in what sounds like a demo take, accompanied by piano and long-time cohort Eric Heywood on lap steel; in the second it’s fully orchestrated. A prayer? A eulogy? With lines like “Find strength from the words of those that went before/take what you need but leave even more,” it’s up to each listener to decide.

What’s indisputable is that Son Volt has made one of the best records of 2005.

(Transmit Sounds/Legacy Recordings)