An album of rock solid classic country and country rock music created by a Canadian First Nations musician and sung in his native tongue, G̱al’üünx wil lu Holtga Liimi is an amazing record.

An album of rock solid classic country and country rock music created by a Canadian First Nations musician and sung in his native tongue, G̱al’üünx wil lu Holtga Liimi is an amazing record.

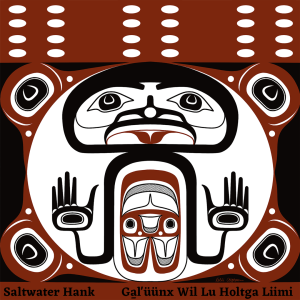

Saltwater Hank is the stage name of songwriter, fiddler, and guitarist Jeremy Pahl, a member of the Gitga’at Ts’msyen community (also known as Tsimshian) in Kxeen, (Prince Rupert), British Columbia. Writing and performing in Sm’algyax, the Ts’msyen language, he’s part of the pushback against centuries of cultural oppression and erasure. His first goal in recording G̱al’üünx is to encourage other Ts’msyen people to connect with their own language, an ancestral tongue that goes back millennia of which there are no first generation speakers left under the age of 60. He also aims to showcase the power of creating in an Indigenous language.

“The fact that I’m singing in my language is an act of resistance,” he says. “Over 150 years after [Canada’s first prime minister John A.] Macdonald and being able to still speak and sing in our language … This really goes to show that he failed. We succeeded in keeping our language and our musical traditions alive.” But any political, linguistic, or cultural significance aside, this is kick-ass music. Maybe the name Saltwater Hank is a nod toward Hank Williams, because his music has some strong similarities. What it also reminds me of is the Cajun country music of D.L. Menard (not coincidentally known as “the Cajun Hank Williams”). Although it’s not entirely apples to apples, both Cajuns and Indigenous people are marginalized groups adapting a cultural expression of the dominant community. (See my review of Shane K. Bernard’s The Cajuns: Americanization of a People.) And those that do it in their own language are able to more easily encode subversive meaning, aside from the sheer benefit of just entertaining their own people in a way that’s meaningful to them.

A perfect example is the second song “Ba’wis,” Sm’algyax for Sasquatch. It’s a tale of his great-great-grandfather’s encounter with one – and he himself claims to have seen one. An outsider can only guess at the layers of cultural meaning in such a song, but why try? This one twangs and rocks hard, and is a great introduction to Hank’s beautiful, craggy baritone.

He follows it up with “Dm Yootu Stukwliin,” on which he lets us in on the joke, singing first in Sm’algyax and then in English about trapping, barbecuing, and eating rabbits on the university campus in Nanaimo, B.C. He alternates between uptempo numbers and slower songs for a well-paced album. “Ndo’o Yaan” is a Crazy Horse inspired rocker, “Liimi Maḵ’ooxs” a peppy two-step with some sweet fiddling from Chloe Nakahara. Alternating with them are slower numbers “Akadi K’uł Waal Nsiip’nsgu,” a Cajun-style two step with more of Nakahara’s fiddling and steel guitar from Liam Mcivor; and the very danceable waltz “Na Waaba Gwa̱soo.” Its lyrics use traditional insults to discuss police violence and oppression, and its title translates to ““The Pig’s House.”

The album is bookended by brief unaccompanied chanted songs that seem to serve as introduction and closure. Just before that final track is one more Crazy Horse style rocker. “‘Nii wila Waalt” is plodding but it rocks hard, Pahl himself fiddling in tandem with a deep distorted electric guitars; I wouldn’t be surprised if this one tackled some dark subject matter.

Saltwater Hank’s record is immensely appealing to anyone who likes old fashioned country, country rock, and roots rock in general. The rockers are gritty, the fiddle and steel guitar lend a country atmosphere throughout, and Pahl’s deep voice with light reverb is perfect for the songs. G̱al’üünx wil lu Holtga Liimi is hard Americana at its best.

(Topic Records, 2023)