I was lucky to get to hear some good old-time banjo recordings recently. There doesn’t seem to be much middle ground when it comes to banjos. There are the folks who love them, and then there are the misguided. I think there’s hope for the misguided, though; they just haven’t listened to the right recordings. These three, for instance.

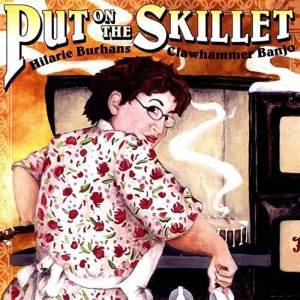

The sound of an egg frying opens Put On The Skillet, leading into “Cluck Old Hen,” where Hilarie Burhans garnishes her banjo picking with vocal cackles (“Let’s cluck this thing up!” she says). That first cut gives a good indication of things to come; the recording has an ample supply of the off-beat. I don’t mean off-beat in the musical sense. Burhans is a dance musician (with Hotpoint Stringband), and her playing is rock-steady. An example of the type of off-beat that I’m referring to would be the version of “Little Sadie,” where Burhans’ voice is processed to sound like it’s coming from an old cabinet-style crystal radio, while Mark Hellenberg’s percussion seems to mimic a skratch DJ. Another might be the swing arrangement of “Shortenin’ Bread,” with it’s cool harmony singing – think Manhattan Transfer with clawhammer banjo – or murder ballad “Pretty Polly” with its whispery lead vocals, and eerie wailing heard in the background.

Burhans is capable of playing it straight when she chooses, though, really cooking on tunes like “Ragtime Annie.” Burhans also plays some driving back-up behind Al Cantrell (mandolin) and husband Mark Burhans (fiddle), who add some sparkling, swinging solos. A couple of banjo and harmonium duets have an introspective feel, and Matthew McElroy joins Burhans on two cuts for some rousing tunes featuring double banjos.

I wish my banjo sounded like this.

I feel obligated to comment on the artwork. I’ve often thought that the demise of vinyl was also the death knell of good cover art, but some artists (Summer Blevins, in this case) have adapted to the new format. The cover of Put On The Skillet depicts Burhans in front of a stove (Horrors! It looks like she’s cooking a banjo!), the backpiece shows a skillet, and the CD itself sports a picture of a fried egg. This is some of the best art I’ve seen on a CD.

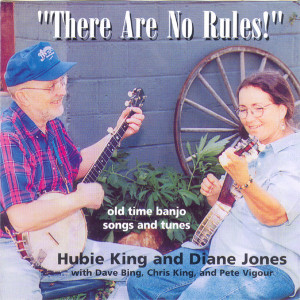

I’d be equally happy if my banjo sounded like that of either Hubie King or Diane Jones. An entire CD of banjo duets might considered twice the fun, except among the aforementioned misguided, who likely consider it twice the misery. Banjo duets aren’t commonly featured on recordings; I suppose they could be considered against the rules, but, as the album title boldly states, There Are No Rules! Actually, going by the liner notes, the dual banjos appear only on five out of twenty-two tracks. The other cuts feature either King or Jones playing solo or joined by fiddle, guitar, and bass.

I’d be equally happy if my banjo sounded like that of either Hubie King or Diane Jones. An entire CD of banjo duets might considered twice the fun, except among the aforementioned misguided, who likely consider it twice the misery. Banjo duets aren’t commonly featured on recordings; I suppose they could be considered against the rules, but, as the album title boldly states, There Are No Rules! Actually, going by the liner notes, the dual banjos appear only on five out of twenty-two tracks. The other cuts feature either King or Jones playing solo or joined by fiddle, guitar, and bass.

Jones plays clawhammer banjo in a very rhythmic fashion, with a lot of punch and drive. Her playing also has a strong bluesy feel to it, as does her singing. Jones’ best pieces are the ones, such as “Boll Weevil” and “Roustabout,” that allow her to exploit the bluesy feeling. Especially good is her “Chilly Winds,” played on a gut-strung fretless instrument. King is adept at a variety of playing styles, from clawhammer to some two- and three-finger methods. His clawhammer playing is somewhat more melodic than Jones’, but still lively. His two-finger work is often bouncy, and on “Lost Gander,” reminiscent of a fingerstyle guitarist. Arguably the most interesting tunes are certain of the duets, where Jones and King play in two different styles — and on “Cumberland Gap,” in two different tunings (tunings for each track are listed in the liner notes). It sounds odd to read about it, but on actual listening it sounds pretty good. No rules, remember.

Diane Jones also appears on Goin’ Back, as part of the Reed Island Rounders, along with Billy Cornette on guitar, and Betty Vornbrock on fiddle. This album focuses on music from West Virginia. The banjo steps out of the limelight on this recording; the focus is on the ensemble, perhaps weighted slightly in favor in favor of the fiddle. Both banjo and fiddle have featured solo pieces, as well.

Diane Jones also appears on Goin’ Back, as part of the Reed Island Rounders, along with Billy Cornette on guitar, and Betty Vornbrock on fiddle. This album focuses on music from West Virginia. The banjo steps out of the limelight on this recording; the focus is on the ensemble, perhaps weighted slightly in favor in favor of the fiddle. Both banjo and fiddle have featured solo pieces, as well.

The fiddling is by turns sweet and wild, the banjo kicks (gently), and the guitar work is steady. The guitar isn’t easily heard most of the time, but rather felt, most conspicuous by its absence on occasional guitar-less cuts. Jones sings on several cuts, with a strong voice, but there’s none of the bluesy material from her previous recording. Most of the tunes are toe-tappers (“Elzic’s Farewell” is a beaut), but the Rounders play some good slow pieces as well. “Queen Of The Earth, Child Of The Skies,” played on a solo fiddle in a drone tuning, sounds much like an Irish slow air (the notes claim it to be a cousin of the Irish tune “The Blackbird”), and the medley of “Springtime Waltz/Paris Waltz” calls for just one turn around the dance floor.

The insert is loaded with tidbits of history and trivia about the tunes, including the banjo and fiddle tunings used. Nice artwork, especially on the disc itself, which sports some odd designs resembling crop circles.

No new ground is broken here; it’s more like an old field tended with loving hands.

(Make ’em Go Wooo, 2003)

(self-released, 1997)

(Burning Wolf Records, 2002)