Anthony Baines’s Bagpipes (Pitt River Museum, Oxford University, 1995)

Kevin McManus’s Ceilis, Jigs & Ballads: Irish Music in Liverpool (Liverpool Institute of Popular Music, 1994)

Tomás Ó Canain’s Traditional Music in Ireland (Ossian Publications, 1993)

Mairéad Sullivan’s Celtic Women in Music: A Celebration of Beauty and Sovereignty (Quarry Music Books, 1999)

David Dodd and Robert Weiner’s The Grateful Dead and the Deadheads: An Annotated Bibliograghy (Greenwood Publishing, 1997)

Howard Orel’s Gilbert and Sullivan: Interviews and Recollections (University of Iowa Press, 1994)

Joni Mitchell’s The Complete Poems and Lyrics (Random House Canada, 1997)

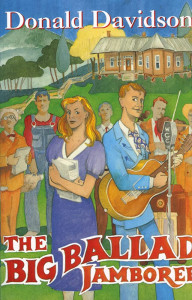

Donald Davidson’s The Big Ballad Jamboree (University of Mississippi Press, 1996)

When I checked the mail this weekend, I discovered that another shipment of music lore books had arrived! It won’t surprise you, my readers, I, a fiddler and lover of music in many forms, collect as much music-related books as possible. This article will, in brief, look at as many of the books that have come in as review copies from my editor. If nothing else, this review will help me clean up, as Brigid has suggested, the pile of books laying on the floor where the catkin have been pushing them about.

When I checked the mail this weekend, I discovered that another shipment of music lore books had arrived! It won’t surprise you, my readers, I, a fiddler and lover of music in many forms, collect as much music-related books as possible. This article will, in brief, look at as many of the books that have come in as review copies from my editor. If nothing else, this review will help me clean up, as Brigid has suggested, the pile of books laying on the floor where the catkin have been pushing them about.

Anthony Baines’ Bagpipes was suggested to me by a piper in a local contradance band when I asked what was the best book on the history of bagpipes. This slim volume, barely 150 pages in length, covers everything about this noble instrument that one needs to know. Without doubt, this is probably the single most exhaustive source on bagpipes and their history that is available online. There are several good books that are almost as good; however, they are published in Europe by various museums and unattainable unless you go to those museums and buy them there. If you are planning on researching the wide-ranging instruments in the bagpipe family including the near-legendary carnyx, it is strongly suggested that this is the first book you read, as anything referred to in subsequent books will make a lot more sense as most bagpipes assume — generally wrongly! — a high-level of technical knowledge. This is not a fancy book — the illustrations are hand-drawn and in black-and-white, but they do the job. Any one interested in bagpipes as an instrument or as a way of torturing one’s kith ‘n’ kin should purchase this book.

Ceilis, Jigs & Ballads: Irish Music in Liverpool is really a chapbook as ’tis only 40 pages long, but what a chapbook it. Liverpool’s been an English-based centre of Irish music for well over a hundred years now. As one band, Ceolta, noted on their website: “The music session scene in the NorthWest is very healthy with Irish music being particularly popular. The quality of the music is further enhanced by the close proximity of the Manchester and Liverpool Irish music scenes.” Liverpool has strong Irish connections that have persisted to the present, and that has resulted in the continuation of the Irish music scene there. Ceilis, Jigs & Ballads is part of the Liverpool Sounds Series that the University of Liverpool is publishing. This chapbook does a fine job of giving both the history of the Irish and their music and the living, breathing tradition as it exists today. And before you ask — a ceili is the same as a ceilidh… The latter is just the Scottish spelling for it. And me guess is that a barn dance, contradance, hooley, and hootenany are just others ways of sayin’ the same thing!

Green Man Review has reviewed many a book concerning Irish traditional music, and Tomás Ó Canain’s Traditional Music in Ireland is a fine addition to that list. A brief description of this book would note the many fine musical examples, the copius texts of song complete with translations from Gaelic, and the fascinating descriptions of the styles of fiddler Matt Cranitch, piper Paddy Keenan, and singer  Diarmuid OSuilleabhain. Did I mention the detailed look at the state of Irish music as it exists today? The author, once an uillean piper with the well-known band Na Filî, gives a masterful look at the real meaning of traditional music in Irish culture. This is not light readin’ to digest as you sip a pint at your favourite pub. This is a serious look at a music that goes well beyond the flash of a Riverdance or the fakery of a faux Guinness pub that has a paid sessuin. (“Sessuin” (sesh-oon), the Irish word for session, in which players get together and play tunes.) If you are interested in knowing everything about Irish traditional music, this book’s a must.

Diarmuid OSuilleabhain. Did I mention the detailed look at the state of Irish music as it exists today? The author, once an uillean piper with the well-known band Na Filî, gives a masterful look at the real meaning of traditional music in Irish culture. This is not light readin’ to digest as you sip a pint at your favourite pub. This is a serious look at a music that goes well beyond the flash of a Riverdance or the fakery of a faux Guinness pub that has a paid sessuin. (“Sessuin” (sesh-oon), the Irish word for session, in which players get together and play tunes.) If you are interested in knowing everything about Irish traditional music, this book’s a must.

Celtic Women in Music: A Celebration of Beauty and Sovereignty is a bloody awful title for a book that’s not really just about Celtic women musicians. It claims it “profiles the careers of thirty artists, singers, musicians, and composers in the Celtic music genre” but I’ll be the Queen of Air and Darkness’s Fiddler if Maddy Prior, Kathryn Tickell, and June Tabor – to name three women profiled herein – are Celtic! And let’s not even mention Shelia Chandra of Ancient Beatbox fame is an English native born of Hindi parents! It’s too bad that Mairéad Sullivan needed to include these folks, as most of the women here, such as Gay Woods and Susan McKeown are indeed Celtic. In this book’s favor, the interviews are — though short — neat looks at various artists. The editor’s got a fair touch as an interviewer, and her writing is informal without being cloying. So pick it up — it’s worth a few quid. Just know you’re getting something that’s not quite as advertised.

Switching away from all things Celtic, we come to The Grateful Dead and the Deadheads: An Annotated Bibliograghy. Yes, you heard me right: an annotated bibliography of the Grateful Dead, the folk rock band that sliced and diced traditional American folk music into a long, strange trip. This type of reference is long overdue. The Rolling Stones, the Clash, and even some group called the Beatles have had bibliographies done for them, so certainly the Dead deserved it, as they were thirty-three years old as a band when this came out. David Dodd (the webmaster of The Annotated Dead, a popular site exploring the literary antecedents and allusions woven into the lyrics of the Dead ) and Robert Wiener,  research librarians slash Deadheads both, have spent great amounts of time on what is clearly a labour of love, and have made an excellent start on this immense undertaking. Deadheads and anyone else interested in American traditional music will be delighted with the results. Is it worth the $75 price tag? I’ll let Mickey Hart render his judgement on that matter: “What an amazing work — a labor of love and a definitive record. I had a feeling someone was out there, someone noticed… Thanks for collecting all the scattered bones, for making history come alive. And thanks for the memories!”

research librarians slash Deadheads both, have spent great amounts of time on what is clearly a labour of love, and have made an excellent start on this immense undertaking. Deadheads and anyone else interested in American traditional music will be delighted with the results. Is it worth the $75 price tag? I’ll let Mickey Hart render his judgement on that matter: “What an amazing work — a labor of love and a definitive record. I had a feeling someone was out there, someone noticed… Thanks for collecting all the scattered bones, for making history come alive. And thanks for the memories!”

I love Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. They combine wicked social commentary with rather brilliant theater craft. They are the epitome of late Victorian theater. And they are halarious to watch!

The operettas that William Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan created were in many ways the direct descendents of John Gay’s pioneering work with The Beggar’s Opera in that what they did was closer to being ballad operas than it was to true opera. Howard Orel’s edited work, Gilbert and Sullivan: Interviews and Recollections, is a joy for anyone interested in a closer look at the men and their work. Together,  Sir William Schwenck Gilbert and Sir Arthur Sullivan created 14 comic operettas that immediately won large, passionate audiences who waited avidly for the next production. But eventually their temperaments caused them to have a bitter falling out. This collection of forty interviews and recollections recording what was said about them during and shortly after their lifetimes by friends, musicians, managers, performers, and writers provides a complex look at their careers both as independent artists and as collaborators.

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert and Sir Arthur Sullivan created 14 comic operettas that immediately won large, passionate audiences who waited avidly for the next production. But eventually their temperaments caused them to have a bitter falling out. This collection of forty interviews and recollections recording what was said about them during and shortly after their lifetimes by friends, musicians, managers, performers, and writers provides a complex look at their careers both as independent artists and as collaborators.

For anyone who has done any reading about G&S, there’s not too much new here, but the useful thing is to have it all together in one place. This is quintessentially Victorian culture at its best. Fans of both English comedy in general and the work of Gilbert & Sullivan in specific should find this book will worth their time.

Joni Mitchell’s The Complete Poems and Lyrics is a fitting addition to my collection of lyric collections. I’m a huge Joni Mitchell fan, and like anyone old enough to vaugely remember the Sixties, I remember her: cool, elegant, and sexy as hell with her husky smoke-infused voice. She was as intrinsic a part of the Sixties as zipless fucks, Bob Dylan, acid, mass protests, and stupid politicians. Like Suzanne Vega, Joni, as one reviewer noted, “has pieced together beautiful prose, vignettes that scream with vivid imagery and honesty.” There’s nothing here but poetry, be it poems or lyrics, so I won’t dwell upon this at length. If you liked Joni, go buy a copy. If you don’t like her, we don’t have much in common!

Switching briefly to fiction, Donald Davidson’s The Big Ballad Jamboree is a novel of love, blind ambition, moonshiners, and Child ballads. It’s set in the fictional Carolina City during the late ’40s, somewhere in southwestern North Carolina. The narrator, Danny MacGregor, is a hillbilly singer at a time when that indigenous folk form is transforming itself into country music. He will go to almost any length to marry his childhood sweetheart, Child ballads scholar Cissy Timberlake. A man without much formal education, he even registers to attend the class on ballads she is teaching at the local teachers college. This lighthearted rollick throught music and love sheds much needed light on the formative days of country music while providing the reader with a tender but realistic romance in which male and female come off as being believable characters. One can’t help rooting for Danny as he tries to save Cissy from the pitfalls of academic politics and a handsome but sleazy moonshiner.

Switching briefly to fiction, Donald Davidson’s The Big Ballad Jamboree is a novel of love, blind ambition, moonshiners, and Child ballads. It’s set in the fictional Carolina City during the late ’40s, somewhere in southwestern North Carolina. The narrator, Danny MacGregor, is a hillbilly singer at a time when that indigenous folk form is transforming itself into country music. He will go to almost any length to marry his childhood sweetheart, Child ballads scholar Cissy Timberlake. A man without much formal education, he even registers to attend the class on ballads she is teaching at the local teachers college. This lighthearted rollick throught music and love sheds much needed light on the formative days of country music while providing the reader with a tender but realistic romance in which male and female come off as being believable characters. One can’t help rooting for Danny as he tries to save Cissy from the pitfalls of academic politics and a handsome but sleazy moonshiner.

What’s interesting to me as a musician is that music forms the very text of this novel: nearly every chapter has a performance of some kind, be it Cissy recording an old woman signing a Child ballad deep in the mountains, or Danny and his group playing hillbilly music that will be used as a radio commercial. It’s especilally interesting in that Davidson contrasts Danny, who represents modernity in his awareness that his band has to be commercially successful in order to be viable, with Cissy who represents the desire of the true scholar to be free of commercial taint. In the end, love and the need to make a livable wage are reconciled, and our lovers are quite happy in the way things work out. The Big Ballad Jamboree is an upbeat and fast read, but one that holds some useful lessons for any lover of folk music.