In 1965 I was sharing a house with four other students, two of whom played the guitar. One day one of the guitarists appeared with an LP by a young man who had recently migrated from Glasgow to London, where he was now installed on the flourishing “folk” scene (the word “folk” being every bit as ambiguous, tricky and treacherous then as it is today). The album, with a cover in shades of blue, black and gray, depicted a young man with unruly hair and the sort of rough clothes favored by folkies. When my friend put it on the player, the young man turned out to have a voice every bit as unkempt as his hair, gruff and expressive with a strange accent, part Scottish and part American, which seemed appropriate given the evident folk, blues and jazz influences on his guitar style.

In 1965 I was sharing a house with four other students, two of whom played the guitar. One day one of the guitarists appeared with an LP by a young man who had recently migrated from Glasgow to London, where he was now installed on the flourishing “folk” scene (the word “folk” being every bit as ambiguous, tricky and treacherous then as it is today). The album, with a cover in shades of blue, black and gray, depicted a young man with unruly hair and the sort of rough clothes favored by folkies. When my friend put it on the player, the young man turned out to have a voice every bit as unkempt as his hair, gruff and expressive with a strange accent, part Scottish and part American, which seemed appropriate given the evident folk, blues and jazz influences on his guitar style.

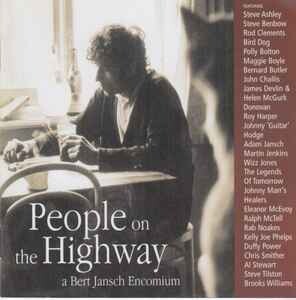

Ah yes, the guitar style! It was for this that my roommate had bought the recording. Unlike the voice and appearance, this was something elaborate and refined. Bert Jansch (the young man’s name – hereafter I shall call him BJ) was one of the principal creators and exponents of what Colin Harper, author of the excellent introduction to BJ’s work in the booklet of this double album, calls “British fingerstyle or folk-baroque,” a style common to BJ and his subsequent musical sparring partner John Renbourn and derived in large part from the pioneering picking of Davey Graham (one of the few contemporaries and near-contemporaries of BJ on the 60s British folk scene who does not appear in this encomium – only the absence of John Renbourn is more striking). Colin Harper also wrote the fascinating study of BJ and his world entitled “Dazzling Stranger: Bert Jansch and the British Folk and Blues Revival” published in 2000. And Harper even plays on this recording, which may be said to have grown out of his biographical venture.

When the first album, entitled simply Bert Jansch, was released, it was not only in London or among my room-mates that aspiring young guitarists tore their hair and wondered how on earth he did it; the malady spread the length and breadth of Britain and then hit Ireland, the USA and other regions too. The rest, as they say, is history, and despite some career ups and downs, BJ has remained a central figure in British roots music. Not surprisingly, given the huge influence of BJ’s work as performer, songwriter and arranger of traditional music, as a member of the innovative and unprecedented “folk-jazz” band Pentangle (with Renbourn) and later in a variety of formats, solo and collective, there has sometimes been talk of producing a tribute to him, an idea that BJ himself tended to discount.

Records honoring long-established performers usually take one of two forms: either an attempt is made to tell the artist’s history by presenting recordings from different periods in his or her career, including outtakes, live performances and rarities as well as a few familiar career highspots, or a collection of admirers is assembled to record songs composed by or associated with the subject of the tribute. In this case the second approach has been adopted. The catalyst for the present double album appears to have been Harper’s book, and indeed it was Harper himself, with Market Square Records backing him, who began contacting BJ’s contemporaries and collaborators (many of whom he had got to know while writing the book) as well as some less probable musicians suspected of admiring his work, to perform BJ’s songs. To their surprise, the would-be compilers ended up with 26 contributions, needing two CDs to fit them all in.

Putting the first CD in the player was an uncanny experience, because it begins with no less than six songs from that groundbreaking first album from 1965, performed almost reverentially and each in its own way pretty reminiscent of the BJ original. These first few performers are mostly contemporaries of BJ and several of them either worked directly with him or at least inhabited the same musical scene. I somehow expected their familiarity over four decades with these songs to make them more willing than respectful younger performers, further removed from BJ’s world, to take liberties and reinterpret his material, but the old stagers really do not. Like BJ’s début album, this recording begins with the song “Strolling Down The Highway,” performed here by the singer and guitarist Chris Smither, who, despite being American and therefore presumably less close to BJ’s work than the succession of British artists on the following tracks, manages to evoke the original version, with only a few extra twiddles on the guitar and his celebrated foot-tapping to distinguish it. Incidentally, Smither is not the only American who acknowledges BJ’s influence: later, on the second disc, we encounter Brooks Williams, singing “Tell Me What Is True Love” and sounding not unlike BJ – he captures the mumbling vocal style well.

But I digress. Next up on the powerful opening sequence is Rab Noakes, a veteran of the English folk scene, whose singing and guitar-playing on “Dreams Of Love” offers another close evocation of BJ, hardly differing from the 1965 original except for the addition of a harmonica. The strong odour of nostalgia is then maintained by a track from another early BJ collaborator, Ralph McTell, whose performance of “Running From Home” shows more vocal sophistication than BJ had in 1965, both in its rich timbre and in the artist’s own voice overdubs, but still manages to recall BJ’s original recording. Continuing the parade of BJ’s contemporaries, we hear Rod Clements, who is better known for his folk-rock work with Lindisfarne but also worked with BJ, singing “Rambling’s Gonna Be The Death Of Me” in a voice almost identical to BJ’s, although the dobro-playing is rather un-Jansch (and also un-Lindisfarne, for that matter).

I did not intend to describe every single cut on both CDs, but these first few pieces really set such a mood and such a standard that they are worth careful attention. This is particularly the case with track six, which is Donovan’s interpretation of “Do You Hear Me Now?” Despite yet more echoes of BJ’s own version, Donovan actually sounds quite like himself (even himself in the 1960s) and it is appropriate that this singer, once preposterously hyped as the British Bob Dylan, should sing what is, in spirit, BJ’s own personal “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” that is to say a sixties protest song. This introductory series of songs from BJ’s first record ends with the sensational “Needle Of Death,” possibly the first anti-drugs song ever, performed by another veteran of 60s acoustic music, Roy Harper, yet again shadowing BJ’s original, despite the audible ageing of Harper’s voice.

From this point on the songs do not appear so obsessed with following BJ’s own recordings so slavishly: Steve Ashley’s take on “It Don’t Bother Me” has an interestingly non-sixties string backing, while Al Stewart’s “Soho” sounds exactly like an Al Stewart song – he sounds just the same as he did 35 years ago, although the guitar duet with Laurence Juber is a super innovation. The other songs all have commentaries by the artist performing them but Stewart’s box is inexplicably empty.

Other British veterans pop up from time to time: indeed, the word “veteran” is particularly appropriate for Steve Benbow who was one of the first musicians to pick up a guitar and use it to accompany traditional British songs as opposed to songs learned from Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Sonny Terry and the like. His “Love Is Teasing”, sung by BJ on his album Nicola reminds us that BJ also performed traditional songs before he started to do so more regularly with Pentangle. A more surprising presence on this encomium is that of Duffy Power, one of the stable of British rockers from the early 60s who, usually at the behest of promoter Larry Parnes, adopted surnames intended to confer instant character on them: Faith, Steele, Fame, Fury, Wilde, Eager. . . . Power here turns in a surprisingly intimate version of “I Am Lonely,” sounding like a jazz crooner with no resemblance to anything that BJ has ever done.

Less surprising is the presence of Steve Tilston, one of BJ’s avowed disciples and himself a composer of importance, even if his biggest successes have usually been interpretations of his songs by other people (e.g. Fairport Convention). “Moonshine” displays Tilston’s own (excellent) style of singing and playing guitar, while the overdub of himself on the arpeggione, sounding rather like a viola da gamba, fits well with his description of this BJ melody as medieval. The real old-stagers also include one of the dominant guitarists of the scene that BJ joined in the early 60s, Wizz Jones, whose performance of “Fresh As A Sweet Sunday Morning” finds him still playing and singing strongly in his own distinctive way. A nice touch is the presence of Jones’s son Simeon, something of a BJ protégé, on flute obbligato.

Martin Jenkins is another contemporary of BJ and his contribution, “Sweet Mother Earth,” has distinct vocal similarities with BJ himself. Playing mandocello, Jenkins succeeds in playing in a style that recalls BJ’s guitar-picking. However, I do not wish to give the impression that this double album consists wholly or mainly of attempts to sound just like BJ. Some pieces are inspired by BJ but clearly set out to do something fresh and original with his material. “A Woman Like You” is played and sung by Johnny Marr’s Healers, whose eponymous leader gave The Smiths their distinctive guitar sound. The drummer on this track is Zak Starkey, and I could not help wondering whether Zak’s father was familiar with BJ’s work, since both men came to prominence around the same time.

Among other contributions that obviously sound quite unlike BJ’s style are Maggie Boyle’s “Bird Song,” which, apart from the obvious difference of being sung by a woman, is accompanied not by a guitar but by a solo cello; and “People On The Highway,” a Pentangle song from the outstanding record Solomon’s Seal that gives this collection its title. It is performed here by a band whose members, all long-time performers who never really made it, ironically call themselves The Legends of Tomorrow and include Colin Harper on guitar – yes, the same man who wrote the notes to this CD and the book about BJ. There are some echoes of Pentangle (Janet Holmes’s voice sounds at times like Jacqui McShee’s) but the overall sound is distinctly folkier than Pentangle, which used jazz and blues licks and, unlike this band, did not include a violin.

There are several other un-BJ-like interpretations on these two CDs, ranging from the Irish bluegrass of the band calling itself Bird Dog to another Irish band, the country-rock duo of James Devlin and Helen McGurk. BJ seems to have had quite an impact in Ireland, as Eleanor McEvoy, composer of the well known song “A Woman’s Heart” also appears here, singing, to her own piano accompaniment, a moving version of “Where Did My Life Go?” McEvoy candidly admits that she assumed that this song was autobiographical. Only later did she discover that BJ wrote it about Sandy Denny. Bernard Butler is not Irish so far as I know (his name could be …) and is much younger than BJ. In fact he was a member of Suede but has worked with BJ and even sounds a bit like him, despite a higher pitched voice. His choice of song, “When I Get Home” is another Pentangle number. Musically, the intrusive keyboard sound takes it a long distance stylistically from BJ’s sound.

Reminding us again that BJ sometimes performed traditional songs, we have here no fewer than two versions of the much-recorded “Blackwater Side,” the first by the American Kelly Joe Phelps, sounding quite unlike BJ, but included here because, like our hero, he somehow manages to combine sounds from blues, jazz and folk into a convincing and coherent whole, although whether BJ’s work had anything to do with this is uncertain. The other version is by the delectable Poly Bolton, once the vocalist of the folk-rock band Dando Shaft and later involved in the Albion Band and other projects led by Ashley Hutchings. Her voice seems to grow richer and more moving as the years go by.

Despite the best intentions of brevity and selectiveness, I find that I have described almost every cut on the two CDs and it would be churlish not to mention the rest. Well, there is a number by John Challis, who shared apartments with BJ in the early 60s: his piece, “1965,” is the only one not composed by BJ, being an atmospheric evocation by Challis’s band of that heady London scene. And that leaves us with just two tracks. Johnny “Guitar” Hodge is a recent BJ sidekick. “Step Back” is a newer BJ song about British society going to the bad and Hodge cleverly and ironically quotes “Rule Britannia” in his guitar backing, which is of a sufficient virtuosity to justify his nickname. Finally, BJ’s youngest son Adam Jansch performs “Morning Brings Peace Of Mind,” singing and playing piano. He sounds nothing like his Dad. His voice is thinner and his piano a bit too obtrusive for my taste compared with the spare tastefulness of BJ’s guitar.

If you are an admirer of Bert Jansch and his music or if you are a fan of the scene onto which he erupted, the London of the 1960s, you will find much to please you on these two discs. They demonstrate the love and admiration that BJ inspired in his own generation and also the influence and affection that can still be discovered in later and more widely scattered musicians. Many of the songs continue to hold their own, even if a few now seem lighter in weight in a changed world, and they are generally performed here with understanding and respect. If you are less familiar with BJ’s work, here is a chance to get to know a score of his best songs with the added advantage that you do not at the same time have to learn to appreciate that very special voice, a mixture of Marlon Brando, Billy Connolly and Louis Armstrong: first get to know the songs and you’ll then realize that it’s worth the effort of loving their master’s voice. This is a startlingly successful collection of good songs, very well performed and recorded.

(Market Square Records, 2000)