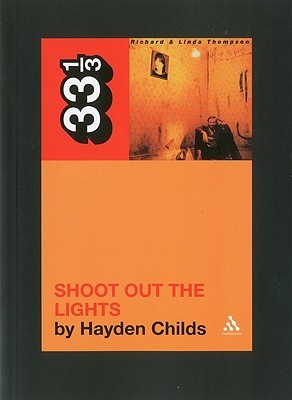

The 33-1/3 book series by Continuum is rightly praised as one of the best and most innovative forms of rock criticism today. In this series, writers take on the subject of a favorite album and write about it in depth. The books in the series so far have covered mainstream fare such as The Beatles’ Let It Be and the Stones’ Exile On Main Street as well as more obscure releases such as Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica; and the non-critically acclaimed such as The Byrds’ Notorious Byrd Brothers. It’s a wonder that it took 57 previous releases before the series got to Richard and Linda Thompson’s Shoot Out The Lights.

The 33-1/3 book series by Continuum is rightly praised as one of the best and most innovative forms of rock criticism today. In this series, writers take on the subject of a favorite album and write about it in depth. The books in the series so far have covered mainstream fare such as The Beatles’ Let It Be and the Stones’ Exile On Main Street as well as more obscure releases such as Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica; and the non-critically acclaimed such as The Byrds’ Notorious Byrd Brothers. It’s a wonder that it took 57 previous releases before the series got to Richard and Linda Thompson’s Shoot Out The Lights.

It’s too bad author Hayden Childs made such a hash of it. Because it is, indeed, one of the best albums of the rock era.

Childs is a good writer. And he knows how to write about music. And he certainly seems to have a good deal of passion and some genuine insights about this album. I just don’t like the way he chose to write about it. He acknowledges up front (in the “Acknowledgments and Other Delights”) that some won’t care for it: “Some may find the narrative strategy I employed surprising, annoying, or even gut-churningly bad, but I’m not sorry, and this isn’t an apology.” Fair enough. I appreciate a writer who sticks to his guns.

Finding himself unable to interview those he needed to interview in order to write about the book, he chose to “write a fiction to illuminate the non-fiction.” And … at the outset, I was willing to go along with the idea.

The fictional conceit is this: Our narrator is a fellow named Virgil who fancies himself a doppelganger of Richard Thompson. He had a musical act with his wife, Bonny, which was not very successful. Their early careers, he fancies, somewhat paralleled those of Richard and Linda; and in 1982, they also broke up, as did the Thompsons. The music on the Thompsons’ final album, Shoot Out The Lights documents the hellish life they lived in the years immediately preceding the breakup. Now, Bonny has died, alone in New York City, and as her ex-husband Virgil has to travel to New York from Florida to take care of her effects. Her death has stirred all kinds of hellish emotions and memories in Virgil, and he relives those memories on his trip up the Eastern Seaboard during hurricane season. And as he travels, he sees his hellish physical journey as a mirror image of Dante’s descent into Hell in his Inferno, and uses that journey as a metaphor for the hell reflected in the music on SOTL.

Got that?

I like the use of Inferno as a metaphor for the spiritual journey taken by the Thompsons in the making of this music. Sure, the construct creaks at times with the burden Childs places on it – for one thing, it requires that the album be more thematically unified than it perhaps is in reality – but it’s a useful device as far as it goes.

And I get that Childs is also using this device to illustrate one great truth about Thompson’s music. Which is that, although you absolutely cannot pin down his songs as autobiographical, you can sift through his art as a whole for clues to the workings of his soul. Indeed, as Childs points out (and others have before him), the songs on this album were written (and in most cases recorded) long before Richard fell in love with somebody else and left his wife and family, so it can’t be strictly considered a “breakup” album. But at the same time, an even cursory look at the songs – and at some on similar themes written and recorded since – reveals a soul tormented by a relationship gone sour. Thus, this book represents a use of fiction to illustrate the truth, in much the same way that Thompson’s songs do. The personas in Thompson’s songs are not Thompson, but they speak his truths, one way and another. The persona in the book is not Childs, but he speaks Childs’ ideas about SOTL.

But Virgil’s journey (get it, Virgil? If not, read your Dante) is just so fraught with melodrama. At its climax, a hurricane destroys the motel room he’s staying in. And he reveals toward the end that he had once considered killing Bonny to get punish her for leaving him. I never believed in this character or cared about him, but Childs required me to spend some serious time with him in the course of this book. Many of Thompson’s characters are unsavory, but they’re compelling because of Thompson’s incredible facility with words, music and that little matter of five strings and a fretboard.

When Childs does write about the songs, he does so quite well. One thing I greatly appreciated was his in-depth comparison of the officially released album with one produced by Jerry Rafferty more than a year earlier and widely bootlegged (and generally known as Rafferty’s Folly). In many cases, he really nails the differences between the performances on the two releases and why the official ones are better. He also tosses in some fun appendices, ranking the albums, grading the career and even comparing Thompson and Neil Young album by album, decade by decade. A nice touch. I just wish he could’ve found some way to stick with the music criticism and left off the fiction.

You can find out more about the 33-1/3 series at Bloomsbury’s website.

(Continuum, 2008)