Rebecca Swain wrote this review.

Rebecca Swain wrote this review.

I once read of Harriet Tubman, a famous African American who several times led American slaves to freedom, that she carried a gun with which to shoot anyone who tried to turn back once they joined her on the journey north. I think of this whenever I hear African American spirituals because for me they embody a raw and bleeding hope, and an unqualified purpose; they say, “I will be free, and you will not stop me.”

Spirituals were the sacred music of American slaves, originating as early as the 1700s. They became especially important in the southern states in the nineteenth century, just before America’s Civil War (1861-1865). Enslaved people were often allowed to sing as they worked in the fields, as long as the songs did not express overt discontent with their lot in life, so they sang spirituals. The words sounded like descriptions of Heaven, references to Bible stories, and generally harmless religious rejoicing.

But the spiritual was a deeply subversive form of music. The underlying message was one of escape to freedom. The words often contained instructions on how to flee north, where African Americans could live as free people. According to the Official Site of Negro Spirituals, the River Jordan mentioned in so many spirituals was really a reference to the Ohio River, the boundary between slave states and free states. Escaped slaves were urged to “wade in the water,” or walk through water in order to throw bloodhounds off their scent. The “home” that enslaved people frequently sang wistfully about was not Heaven so much as free northern states, or even Canada. When a listener filters the lyrics through this knowledge of their symbolism, seemingly sweet, resigned religious songs suddenly show themselves to be fiercely political and single-mindedly determined.

Consider these lyrics to “Swing Low Sweet Chariot,” a song schoolchildren often learn in this country:

Swing low sweet chariot

Comin’ for to carry me home.

Looked across the Jordan

and what did I see

Comin’ for to carry me home

A band of angels comin’ after me

Comin’ for to carry me home.

A song about dying and going to Heaven? No! It was a plan to escape to the north with the help of the Underground Railroad, a loose organization of white and black people sympathetic to escaping slaves. But Master wouldn’t know that when he heard the song sung in the fields.

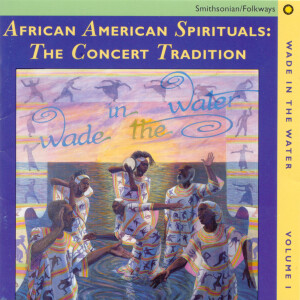

As the title of this disc indicates, the spirituals in the collection under consideration are performed in the concert tradition, as opposed to the gospel tradition. According to the informative liner notes, the concert tradition originated in 1871 with the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who toured northern America trying to raise money for their college by giving concerts. As time went on, classically trained musicians changed the songs from the raw, ragged, unschooled versions sung by actual slaves to more polished, harmonious versions more palatable to white audiences. This new style of singing spirituals points up the gradual change in African American culture as larger numbers of former slaves received an education and became influenced by European styles of music, as opposed to the African styles they had honored on the plantations.

Four groups of performers are represented here: The Fisk Jubilee Singers; Howard University Chamber Choir; Florida A & M University Concert Choir; and a community group, The Princely Players, from Nashville, Tennessee. There is also a solo performance, powerful and mournful, by Kehembe Eichelberger, of “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.”

This is a collection of well-known spirituals, many of which will be familiar to schoolchildren and high school choir members: “Swing Low Sweet Chariot,” “Ezekiel Saw the Wheel,” “There is a Balm in Gilead,” “Roll Jordan Roll,” and two versions of “Wade in the Water,” among others. Because these songs are arranged to be performed in concert, the renditions are smooth and perfect, with lovely harmonies and swelling crescendos.

I have no criticism of this collection; it is lovely. I will just say that I prefer to hear spirituals sung with more heart and raw emotion, more fidelity to their original sound. I consider spirituals to be a vitally important testimony to American history, and in my opinion the concert tradition takes them too far away from the original voices of the men and women making that testimony. But this is just my preference. Anyone who purchases this CD is in for a beautiful listening experience.

(Smithsonian/Folkways, 1994)