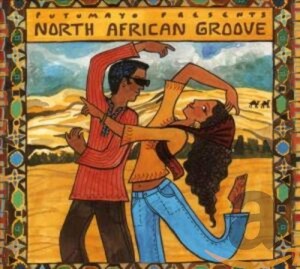

Here is another compilation from Putumayo, the world music specialists. This is contemporary popular music from North Africa and it illustrates remarkably well how totally global our, and everyone else’s, village now is. For while being unmistakably North African, the music presented here has distant, and sometimes not so distant, echoes of sounds from a wide variety of other traditions. Is there a popular music anywhere in the contemporary world that remains totally uninfluenced by what’s going on elsewhere on the planet?

Here is another compilation from Putumayo, the world music specialists. This is contemporary popular music from North Africa and it illustrates remarkably well how totally global our, and everyone else’s, village now is. For while being unmistakably North African, the music presented here has distant, and sometimes not so distant, echoes of sounds from a wide variety of other traditions. Is there a popular music anywhere in the contemporary world that remains totally uninfluenced by what’s going on elsewhere on the planet?

This particular compilation is the seventh in Putumayo’s “groove” series, by which they appear to mean that there is no track that you couldn’t dance to. The influences that overlay the basic sounds of Arab North Africa are varied, but seem to be overwhelmingly Cuban and European, much less North American or Sub-Saharan. The European connection is not hard to explain, since several of the countries from which the musicians come were European colonies or protectorates until World War II and after, and since independence there has been a population movement from the countries bordering the Sahara to Europe, where Arab and Arab-descended populations have brought their own cultural – including musical – traditions and blended them with what they encountered in the metropolitan countries.

In 2002 I reviewed a compilation of North African (essentially Algerian and Franco-Algerian) raï music. As I pointed out then, raï, which is variously translated as opinion, judgment, advice, objective, point of view, will or outlook, maintains – even when it is in a debased form – an ancient North African tradition of philosopher poets putting their ideas into verse. Raï is the music of rebellion in the cities of Algeria and, later, the high-rise Arab ghettoes of modern French cities. This Putumayo selection is somewhat removed from this tradition. The music is decidedly more mainstream and less rootsy and also displays more marked extraneous influences. It is pop music which, even if in places it inevitably has echoes of more noble musical traditions, has few philosophical pretensions.

The CD gets off to a superb start. Of all the unlikely combinations, Jomed is an intriguing Algerian/Cuban band. One can only speculate how these two musical traditions came together, but Jomed’s song “Montuno Noreño” is sung in Arabic and Spanish, combining North African singing style and instruments with Cuban percussion, marimba and brass, all unusual in this context. There is, however, a certain logic in this particular fusion, for it is nothing less than an attempt to reunite the Arab-Andalucian music that has roots in Moorish Spain and the Afro-Spanish music that developed in Spanish-ruled Cuba – and it works remarkably well.

Cuban and Maghreb music is clearly a marriage made in heaven, because track 5, the song “Un Mot De Toi,” performed by Rhany from Morocco, across the narrow strait from formerly Moorish Spain, not only displays a strong Cuban influence, especially in the typically Cuban piano and much of the percussion, but the CD was actually recorded in Cuba, where the artiste had gone in search of a “Buena Vista” sound. Just as Jomed’s song mixes Arabic and Spanish, so Rhany sings in a mixture of French and Arabic. It is a noticeable characteristic of this kind of pop music that the singers seem at ease switching between Arabic and the European languages – mostly French, sometimes Spanish – of their former colonizers, whose countries at least some of them have settled in.

If Jomed and Rhany have sought inspiration in Cuba, Samira Saeid from Morocco performs much more conventional Arab pop music with a disco beat and some electronic assistance. Like so many Arab artistes seeking a sophisticated audience, she moved to Egypt to be in the mainstream of North African popular music and her track “Aal Eah” is typical of her popular output. Amr Diab, who sings “Nour El Ain,” is is actually from Egypt, and is a very big star who is an idol of North African pop. He too has absorbed European and Latino influences and packaged them in a distinctive style that has conquered much of the Maghreb. His song uses the word “habibi” dozens of times: it’s Arabic for “darling” and you won’t listen to modern Arab pop for long without hearing it. This song features distinctly European-style guitar-playing and almost a Buddy Holly beat.

Faudel, another singer of Algerian origin, goes in for more electronics and performs in a mixture of Arabic and French on his slightly repetitive “Si Tu Veux,” reflecting the fact that he came to prominence in France, in the raï diaspora that took Algerian music to Europe. One could say something similar about Amina, who hails from Tunisia but has found big success in France. Her song “Dis-moi pourquoi” also mixes mainly French and a little Arabic. Amina is so big in France that her music is really French pop with an Arabic accent. There is a certain logic in this gradual dilution of the “pure” Arabic coffee with French milk: a generation of young French people whose families’ roots are in North Africa are growing up speaking French and with a scant understanding of Arabic and the musicians of their tradition have to appeal to an audience that feels at home in the French language.

The importance of Egypt for the development of the new North Afrian sounds is underlined by the presence on this CD of Cheb Jilani’s “Bahebbak.” Jilani is a Cheb (a sort of cool dude) from Libya but has also made his base in Egypt, the center of Arab pop music. Although this track was recorded there, it is a long way from Jilani’s Arab roots, for the alien accordion is very prominent, and the accompanying strings and backing chorus are all very pop, with only the occasional burst from the orchestra to remind us of the singer’s folkier origins.

If Egypt is where many North African musicians work, Algeria seems to be the real cradle of much of the new North African pop music, for it is where raï was born. Hamid Baroudi is another Algerian featured on this album. On “Sidi” he uses funky brass and driving percussion that demonstrate his capacity to listen to and learn from the West’s music.

A musician who has successfully made the crossover from the narrow market for raï to a broader popularity is Khaled, previously known as Cheb Khaled. “Ya-Rayi,” which he sings here, is the title track from his 2005 album. It marks a return to the raï sound and is even sung in Arabic, although the strident brass plays in something very like a jazz big band style and there’s electric guitar and organ in there, too. This is a big production, as befits the man who is still the greatest raï singer of his generation and far and away the most successful of all raï performers, who enjoyed international success with his song “Didi.”

Cheb Mami is another of raï’s biggest stars, who also lives, and mostly works, in France. He has appeared as a vocalist on Sting’s album “Brand New Day,” which raised his profile outside his own world. His contribution here, “Viens Habibi” is yet another example of a singer of Algerian origin singing in French, asking his habibi to “Come here darling.” Like all the performers on this CD, Mami uses percussion that is a far cry from the traditional drumming of North Africa and combines European and Latino influences. In Cheb Mami’s case, the beat kept up by the percussion is unusually subtle. This is a highly distinctive track, one of the best things on the album.

It seems that if North African pop stars have not settled in France, they are to be found in Egypt, and this is the case of Mohamed Mounir. He hails from remote Nubia in the deep south of Egypt and came to fame performing music in his own local tradition, but this is very western-influenced pop, both in structure and in instrumentation, and also uses electronics. Only the Arabic-lanuage singing and some of the percussion betray the origins of what is not, despite its pedigree, a particularly North African sounding piece. Mohamed Mounir is alleged to be influenced by reggae, but there is only the faintest trace of it here in occasional noises from the percussion.

The CD ends with a song by the oddly named Eastenders, with the addition of Shady Sheha. It is a very odd combination, composed of a Turkish/German duo joined by an Egyptian singer, but it works. The two musicians succeed in performing on percussion, guitar and flute and also use some some technical wizardry, while Sheha sings. For this particular listener it tends to go on a bit too long, but there is admittedly a lot in there to hear.

This CD is much more “pop” than the similar Rough Guide compilation of four years ago. It gives a very good overview of the sort of popular music that is now being listened to in both the Middle East and in the North African-descended communities in Europe, especially in France. The dilution of traditional Arab forms and styles is a fascinating illustration of what is happening to musical cultures everywhere. Much of it is not really for me once my curiosity has been satisfied, but it’s worth a listen, and if you hear samples online you may decide that you want to explore this genre further. You may also like to know that a portion of the proceeds from the sale of this CD will be donated to Search For Common Ground in support of their efforts to find peaceful solutions to conflict in the Middle East and around the world.

(Putumayo, 2005)