Long, long ago, in a world far more uptight about hem lines and shirt collars than we are today, Karl Wagner’s Kane joined the ranks of timeless heroes Conan and Fafhrd on the printed page. Fans of Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber will find much to enjoy in these stories, but Midnight Sun bends on a path all its own, away from those “other” barbarians, reminding us of the origins of the fantasy genre along the way.

Long, long ago, in a world far more uptight about hem lines and shirt collars than we are today, Karl Wagner’s Kane joined the ranks of timeless heroes Conan and Fafhrd on the printed page. Fans of Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber will find much to enjoy in these stories, but Midnight Sun bends on a path all its own, away from those “other” barbarians, reminding us of the origins of the fantasy genre along the way.

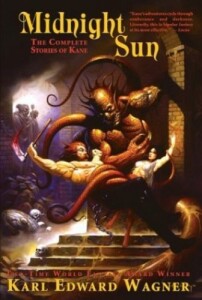

The cover, drawn by Ken Kelly, evokes the older world these stories belong to; on the steps of an ancient temple, a many-tentacled demon seizes a red-haired barbarian and half-naked girl in its coils. The barbarian’s axe and the steps they struggle on are stained with blood, and the demon itself is clearly preparing to finish the man off so that it can drag the damsel off for atrocious uses. The text of the cover is carefully placed to avoid obscuring the artwork, and the only part slightly difficult to read is the line near the base proclaiming Wagner as a “Two-Time World Fantasy Award Winner.”

Flipping open the cover reveals a map that, unlike the glossy, lurid cover, looks like it was drawn with a ballpoint pen. Curious about the inconsistency, I turned to the credits page to find a note that the map was “drawn by Snow, based on an original map by Dale E. Rippke.” There’s also a note thanking Mr. Rippke for his “genourous support” and help with this book. An internet search turned up Rippke’s home page, which is a stunningly thorough compilation of information on all things Kane. He’s also posted similar information on other heroic dark fantasy heroes such as Conan and King Kull, and has scanned in examples of cover art for just about every book he talks about. Many covers depict — what else? — muscular barbarians in various poses.

These days, a “mighty-thewed barbarian” is so stereotyped as to be a mockery and Wagner’s rather heavy prose is far from fashionable — but there’s still something that draws you back into the stories, over and over. I believe the fascination comes primarily from the character. Kane is warrior and wizard rolled into one huge, red haired package. His blue eyes burn with the “mark of Kane” — a point that’s hammered throughout every story, those “killer’s eyes.” They identify him, to those who know their legends, as the fratricidal, gods-cursed wanderer from the beginning of the world. Wagner chose to spell the name ‘Kane’ rather than ‘Cain’ for two very good reasons: to keep the Biblical concept from overshadowing the character and to produce a moment of shock when the reader first realizes who Kane is.

Who is Kane? Or what is Kane? Which side is he on, anyway? His own, is the short answer — he’s completely amoral, a difficult concept to pull off as a sympathetic main character. Yet by the end of this book, I was sympathetic — to a man who is a murderer, rapist, extortionist, thief, bully, and all the things I despise in the “real world.” What turned the initial disgust to reluctant alliance is the skillful way Wagner weaves the stories around his dark and brooding anti-hero, showing us this side and that side, never trying to convey the whole in any one story.

In the first story, “Undertow,” Kane is shown as a cruel jailer of an innocent woman, and is portrayed as a monster throughout, until the final page, where the situation is neatly flipped back on itself in a surprising twist. Kane is still cruel but there’s a certain resonance with the cruelty, a hanging question: what would you do if you were immortal and wanted a love to last? “Undertow” isn’t an easy read, as it skips back and forth between past and present — I had to go through it twice, to pick up on the tiny clues that place the events in a relevant time frame. Hint to reader: watch for the first mention of that emerald collar …

The second story, “Two Suns Setting,” turns to another facet of the big warrior-wizard. He meets Dwassllir, one of the last giants, while traveling through the desert. They engage in a philosophical discussion about the differences between their races, and Dwassllir winds up inviting Kane to travel with him. Together, they find the lost tomb of the great giant king named Brotemllain. Wagner shows us Kane in a more sympathetic light this time by pairing him with a companion who’s at least his equal — if not his superior, the subject of their early debate — and by keeping Kane’s cruel side out of the story completely.

“The Dark Muse” is where I really became hooked on this book. I have a weak spot for writers and people who appreciate them. In this story, Kane shows his literate side in discussions with a poet friend of his, Opyros, who seeks to write the “perfect” poem. With a touch of Kane’s cruel side emerging in the process, circumstances bend to allow Opyros to meet “Klinure, the muse of dream, whom some call the dark muse.” Klinure’s embrace enables the poet to reach the perfection he desires, but perfection isn’t always what you expect it to be.

The basic plots of all stories in this book, which range from prehistoric to modern and even futuristic settings, can be broken down into such simple terms and explanations, but that misses the brawny vitality filling the pages. Inspired by Wilde, Lord Gro, and Marlowe, Wagner used his training as a psychiatrist to gift Kane with a more complex personality than many writers give “good” heroes. “For every fifty people who’ve heard of Dracula,” Wagner claimed, “only one can identify Jonathan Harker.” A long essay at the back of the book gives a deep and fascinating look into the heart and history of not only Kane, but Wagner as well.

An even braver offering is an early version of a published story. “The Treasure of Lynortis” was written, Wagner admits, “by a very earnest teenager,” and it shows. The prose is thick enough to choke an elephant and there’s far too much “telling” instead of “showing,” but those problems were eventually ironed out as Wagner gained experience. The story was published much later as “Lynortis Reprise,” a thoroughly enjoyable story.

There are also poems scattered throughout the book, some in stories and some set to stand alone. They aren’t happy poems, they aren’t rhymed, they don’t really scan in any recognizable format — but there’s an odd rhythm to them all the same, and they do evoke a mood of immortal melancholy and eternal change which suits this book very well.

Unfortunately, Wagner himself was far from immortal. In 1994, he lost his final battle, and we lost a great weaver of fantasy. As Stephen Jones notes in the introduction, “[w]ith his tales of Kane . . . Wagner’s skills as a storyteller flared brilliantly, and in the end that’s the best any writer can ever ask for — if only for a short while . . . .”

In the process of researching for this review, I came across an exciting piece of news: three of the stories in this collection may be made into movies. Tonic Films picked up the rights to the collection “Death Angel’s Shadow,” which includes “Cold Light,” “Mirage,” and “Reflections for the Winter of My Soul.” The producer, Lauren Moews, is known to many for her 2003 film Cabin Fever, which gathered responses similar in polarity to reviews of The Last Passion. Hopefully “Reflections,” the first story scheduled to be translated to film, will have a more favorable — and less controversial — reception.

(Night Shade Books, 2003)