The Waterboys’ The Waterboys (Ensign, 1983)

The Waterboys’ A Pagan Place (Ensign, 1984)

The Waterboys’ This Is The Sea (Ensign, 1985)

The Waterboys’ Fisherman’s Blues (Ensign, 1988)

The Waterboys’ Room To Roam (Ensign, 1990)

The Waterboys’ Dream Harder (Geffen, 1993)

Mike Scott’s Bring ‘Em All In (Chrysalis, 1995)

Mike Scott’s Still Burning (Chrysalis, 1997)

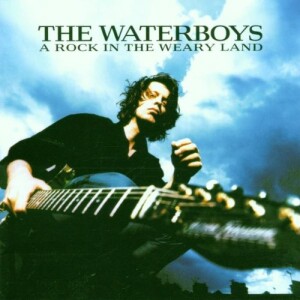

The Waterboys’ A Rock in the Weary Land (RCA, 2000)

After two decades as a prolific recording and performing, artist Mike Scott is still perceived as something of an enigma. The movers, shakers and self-appointed scene setters of the music business have often viewed him as deliberately contrary, a loose canon. Reviewers, confused by his frequent stylistic changes of direction have sung his praises and poured out scorn and derision in almost equal measure. Many of his faithful fans have cast him in the mould of a mythical hero – a Celtic soul, a poet, a journeyman mystic with a rock ‘n’ roll heart. It’s a role that he appears to neither court nor feel entirely comfortable with. Whilst almost every Tom, Dick and Noel who’s ever strapped on a guitar and rhymed moon with June has accumulated a stack of biographical tomes to test the weight-bearing capabilities of Ikea’s finest coffee tables, the Mike Scott story remains untold. Except that it doesn’t; it’s written across the CD’s reviewed here.

After two decades as a prolific recording and performing, artist Mike Scott is still perceived as something of an enigma. The movers, shakers and self-appointed scene setters of the music business have often viewed him as deliberately contrary, a loose canon. Reviewers, confused by his frequent stylistic changes of direction have sung his praises and poured out scorn and derision in almost equal measure. Many of his faithful fans have cast him in the mould of a mythical hero – a Celtic soul, a poet, a journeyman mystic with a rock ‘n’ roll heart. It’s a role that he appears to neither court nor feel entirely comfortable with. Whilst almost every Tom, Dick and Noel who’s ever strapped on a guitar and rhymed moon with June has accumulated a stack of biographical tomes to test the weight-bearing capabilities of Ikea’s finest coffee tables, the Mike Scott story remains untold. Except that it doesn’t; it’s written across the CD’s reviewed here.

Writing in Melody Maker, reviewer Robin Gibson stated that “The Waterboys are Mike Scott, and this is a long overdue collection of his songs.” This album was certainly a long time in the making. The beginnings of The Waterboys can be traced back to 1977 when a young Scott started a degree course in English Literature & Philosophy at Edinburgh University. He left within a year, having discovered that Patti Smith and The Clash inspired him more than Shakespeare did. He became a zealous fanzine writer and editor before inevitably, a singer, songwriter and musician in his own right.

There followed a series of low-key recordings and short-lived groups, including Another Pretty Face and Funhouse, before Scott decided to employ a do-it-yourself approach in 1981-1982. A half dozen of the resulting songs, performed on various guitars, keyboards and drum machine, form the core of The Waterboys released in 1983. It remains an extraordinary record. It is literate rather than literal, bold and impassioned, reaching towards something beyond the understanding of Scott’s “contemporaries,” of the time. Let’s face it, if the height of your ambition is to make a few quid, get laid and appear on TV, you don’t open your debut album with a song like “December.”

“December fell deep in the bleak midwinter time, when Jesus Christ howled a Saviour baby’s howl – a primal truth as pure as ice.”

“A Girl Called Johnny,” is a paean to Patti Smith, driven by the wild, tumbling saxophone of Anthony Thistlethwaite. “The Three Day Man,” is a forthright assertion of self-assurance containing lines like “you know I want you, you know that I love you, but I’ll never need you anyway.” Whilst the song appears to be addressed at a specific individual, it can perhaps, also be viewed as an indication of Scott’s relationship with the music business – “you have to live with every decision you make but that doesn’t mean that I’ll be your slave.” I’d advise caution though, that kind of analysis has been driving Bob Dylan obsessives mad for years!

“Gala,” “I Will Not Follow, “and “It Should Have Been You,” address feelings of loss, betrayal, despair, redemption, rage, and disappointment in unfulfilled potential. Not for the last time however, there’s nothing to invite accusations of “miserable singer-songwriter indulgences,” in Scott’s words and music. These songs brood, swing and rock with a confident musicality.

“The Girl in the Swing,” is a slow piano-based love song that Nick Cave would give his eye-teeth for tomorrow. The album’s closer, “Savage Earth Heart,” finds Scott pounding away at an acoustic guitar and asking “Will you lay all of your deepest, wildest secrets bare? Will you let all of those rumbling old gods take rage?” A tantalizing glimpse into the Waterboys future (on several levels), and significantly, the one song from this album that’s regularly performed to this day.

Whilst the sound may seem dated across the years (Linn drums, anyone?) and Scott’s voice lacks the authority that it gained with subsequent maturity, the songs on The Waterboys still sound as fresh as a daisy and as startling as a summer rainstorm. At the time of writing, the album’s just been re-mastered and expanded. If you missed this all those years ago, then that’s as good a reason as any to go back to the beginning of The Waterboys story.

- Further reading – C.S. Lewis’s That Hideous Strength, Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee

- Further listening – Patti Smith’s Horses, David Bowie’s Hunky Dory.

A Pagan Place documents The Waterboys metamorphosis from Mike Scott’s flag of convenience into a fully-fledged band. Scott and Thistlethwaite were now joined by Karl Wallinger (piano, organ, percussion, backing vocals), Kevin Wilkinson (drums), Roddy Lorimer (trumpet), and Tim Blanthorn (violin). All were drafted for the recording, along with various backing singers including Eddi Reader and TV Smith.

A Pagan Place documents The Waterboys metamorphosis from Mike Scott’s flag of convenience into a fully-fledged band. Scott and Thistlethwaite were now joined by Karl Wallinger (piano, organ, percussion, backing vocals), Kevin Wilkinson (drums), Roddy Lorimer (trumpet), and Tim Blanthorn (violin). All were drafted for the recording, along with various backing singers including Eddi Reader and TV Smith.

The impact of the enlarged line-up is demonstrated from the outset on “Church Not Made With Hands.” The song begins with a chiming acoustic guitar. There are a few chords from the piano, and then the drums roll like approaching thunder, reaching a crescendo just as Thistlethwaite and Lorimer’s horns come in with the swagger and power of a Stax soul revue. All of that happens before the song’s opening syllable. It’s clear that Scott’s discovered his muse and isn’t shy about declaring it from the rooftops – “she is in the shadows, ocean and the sand, everywhere and no place, her church not made with hands.”

While Scott and his invisible muse were soaring together on some unseen psychic plane, things weren’t going so well for him in the earthly realities of a recent relationship. The next three songs all deal with a break-up and its aftermath.

“All The Things She Gave Me,” describes in cathartic detail how Scott attempted to exorcise the too-recent memory of a lover by carefully gathering all of her gifts to him into a box, driving it across the city to a significant location, and setting it on fire. Scott, like Dylan, isn’t afraid to occasionally appear unpleasant, if it makes for a better song.

“The Thrill is Gone,” takes a tone of weary acceptance rather than the previous song’s self-righteous anger. “I’m too tired to deceive you, we can’t pretend there’s nothing wrong. Who’ll be the first to say it, that the thrill is gone?” The song features the first appearance of a violin on a Waterboys song, an instrument that was to become central to much of their music in subsequent years. By “Rags,” Scott is ready to express regret and remorse. “Everything is rags and there’s nobody to blame but me… (I) Wanted nothing more, my loved one, than to wrap you up in joy,” and finally, in a neat reversal of “All The Things,” “I will burn me right out of this place, I will lay you down to sleep so when you wake I’ll be gone and you will remember nothing.”

Having taken the listener through anger, acceptance and healing, what’s left but to move on? All aboard the train then, for the railroad shuffle of “Somebody Might Wave Back.” “We’re riding through some place where I’ve never been, and I’m waving through the window as we go.” The restless wanderer is back, with a full heart and an open mind, carrying only his anticipation into a vista of limitless possibilities.

What he finds is, “The Big Music,” which, apart from being the most commonly used term for the Waterboys sound during this period, appears to be Scott’s name for his own artistic and spiritual epiphany. He knows that he’s onto something special but doesn’t claim to be the source of it – “I just stuck my hand up in the air and everything came into colour like jazz manna.” This lyric always reminds me of an interview with Keith Richards (a man not widely regarded as any kind of holy evangelist) who mused that sometimes “songs are floating in the air, you’ve just got to grab ’em.”

“Red Army Blues,” is an account of a young Russian soldier during and immediately after the Second World War, sung in the first person. It’s a fine, dramatic narrative fleshed out by atmospheric saxophone but is, in retrospect, something of a distraction to the flow of the album as a whole.

“A Pagan Place” seems to pick up where “The Big Music” left off. Only Scott knows the details of his journey but he’s asking “How did he come here, who gave him the key? Who put the colour, like lines on his face and brought him here, to a pagan place?” The song builds in intensity from beginning to end in a scorching performance.

I’ll end the review of this album with another lyric from “The Big Music.” “I have seen the big mountain and I swear I’m halfway there.” If this album was merely “half way,” then what on earth were we supposed to expect from the next one?

This album is now available in re-mastered and expanded form on CD.

- Further reading – Edna O’Brien’s A Pagan Place, William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience.

- Further listening – The Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street.

On This is the Sea the Waterboys are listed as Mike Scott, Anthony Thistlethwaite and Karl Wallinger. The drumming duties are split between Kevin Wilkinson and Chris Whitten while Lu Edmonds and Matthew Seligman handle the bass parts. Roddy Lorimer’s back too and it’s his trumpet that fanfares in “Don’t Bang The Drum,” in a manner more akin to a spaghetti western soundtrack than a pop record. The tension builds, leaving the listener waiting, but for what? The answer comes in a question as the band come in rocking and Scott’s voice delivers the line, “Here we are in a special place, what are you going to do here ….. What show of soul are we going to get from you?” The song is a stunning opener that serves as both a plea for, and demonstration of, artistic integrity over the safe and predictable option.

On This is the Sea the Waterboys are listed as Mike Scott, Anthony Thistlethwaite and Karl Wallinger. The drumming duties are split between Kevin Wilkinson and Chris Whitten while Lu Edmonds and Matthew Seligman handle the bass parts. Roddy Lorimer’s back too and it’s his trumpet that fanfares in “Don’t Bang The Drum,” in a manner more akin to a spaghetti western soundtrack than a pop record. The tension builds, leaving the listener waiting, but for what? The answer comes in a question as the band come in rocking and Scott’s voice delivers the line, “Here we are in a special place, what are you going to do here ….. What show of soul are we going to get from you?” The song is a stunning opener that serves as both a plea for, and demonstration of, artistic integrity over the safe and predictable option.

“The Whole of the Moon” comes next, with its lyrical images dazzling and tumbling like a waterfall. Playful, passionate and poetic in equal measure, when this was released as a single it seriously threatened to catapult the “big music,” into the big-time. To this day it’s unthinkable in many UK pubs to declare “closing time,” before some happy man’s risen from his seat to declare that “I saw the rain-dirty valley, you saw Brigadoon! I saw the crescent; you saw the whole of the moon.”

“Spirit” follows, achieving its objectives by following the exact opposite course. A basic, repeating figure on acoustic guitars, mandolin and piano provides the space for Scott to deliver a lyric constructed with the beauty and simplicity of a haiku. “Man seems. Spirit is. What spirit is, man can be.” “The Pan Within,” is an enticing voodoo-mantra, snake of a song. “Spirituality,” becomes inseparable from “sensuality,” and “nights like these were born to be sanctified by you and me.” Steve Wickham, a veteran of U2 sessions, was recommended to Scott by Sinead O’Connor, plays the hypnotic fiddle on this song.

“Medicine Bow” is Scott flying high and running fast, fuelled by creative energy – “I’m going to tug at my tether, I’m going to tear at my lead, I’m going to test my knowledge on the field of deeds.” The band’s right there with him, free wheeling, loud, fast and unstoppable. This isn’t the sound of one man’s ego reveling in it’s own euphoria. Scott wants everyone to feel like this: “Run with me, fast as we can go,” he urges. He’s not blind to what’s actually going on around him however, as he points out on “Old England.” Here, Scott mourns that his adopted homeland has become a dying civilisation. When he sings of a land “where criminals are televised, politicians fraternise, journalists are dignified and everyone is civilised, and children stare with heroin eyes…” you can hear his heart breaking.

It’s anger, rather than sadness that comes to the fore on “Be my Enemy.” Who, (or what) that enemy may be is never made explicit, but whatever he, she or it was, Scott’s not in the mood to mess about any longer. “Trumpets,” sends the needle on the emotional barometer swinging out of the red and lodges it firmly in the section marked “love.” Scott’s head is so full of the stuff that it’s going to burst if he doesn’t let it out. This love is so huge that it can only be likened to nature and religion. “Your love feels like trumpets sound. Your life is like a mountain and your heart is like a church with wide open doors,” It’s breathless, exhilarating stuff, and sets the listener nicely up for the album’s final track. And where do we find Mike Scott in “This is The Sea?” Back on the train with his trusty acoustic, fearless of the future and dismissive of the past. “That was the river – this is the sea.”

- Further reading – Dion Fortune’s The Goat-Foot God.

- Further listening – Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, John Lennon’s “Mind Games,” Patti Smith Group’s Easter, Prince and The Revolution’s Purple Rain.

Following the critical and (comparative) commercial success of This is the Sea proved to be anything but plain sailing. Wallinger left the Waterboys to pursue his own song writing direction. A slew of British groups latched onto the Waterboys distinctive sound and started raiding the charts with their own versions of it. This might have been all right had, for instance it been another case of Peter, Paul & Mary producing radio-friendly versions of Bob Dylan songs. It wasn’t, and most of these “original,” efforts (lacking the vision and articulacy of Scott’s lyrics), came across as lumpen and bombastic. With Scott’s “big music” rapidly turning from a milestone to a millstone, something had to change. Scott was considering a move to New York when Steve Wickham suggested that a short visit to his home in Dublin might help his friend to relax and focus before making any major decisions. Scott accepted the invitation and stayed in Ireland for the next five and a half years.

Following the critical and (comparative) commercial success of This is the Sea proved to be anything but plain sailing. Wallinger left the Waterboys to pursue his own song writing direction. A slew of British groups latched onto the Waterboys distinctive sound and started raiding the charts with their own versions of it. This might have been all right had, for instance it been another case of Peter, Paul & Mary producing radio-friendly versions of Bob Dylan songs. It wasn’t, and most of these “original,” efforts (lacking the vision and articulacy of Scott’s lyrics), came across as lumpen and bombastic. With Scott’s “big music” rapidly turning from a milestone to a millstone, something had to change. Scott was considering a move to New York when Steve Wickham suggested that a short visit to his home in Dublin might help his friend to relax and focus before making any major decisions. Scott accepted the invitation and stayed in Ireland for the next five and a half years.

By the time that Fisherman’s Blues emerged Scott had immersed himself in Ireland’s uniquely open, inclusive and diverse musical culture. (The last time that I was in Dublin a traditional fiddler friend took me to a bar where her regular tin whistle and guitar player was performing. Expecting jigs and reels I found him blowing tenor sax in a fantastic electric jazz band. After the gig we met Bono on the street…)

While Scott, Thistlethwaite, Wickham and Trevor Hutchinson (bass) were now the core members of The Waterboys, all constraints ceased to exist as sympathetic musicians came out of the pub sessions and into the studio. Traditional giants Alec Finn, Vinnie Kilduff, Mairtin O’Connor and Charlie Lennon all appear. Colin Blakey (from Wee Free Kings) makes several telling contributions and even Jay Dee Daugherty (from the Patti Smith Group) gets in on the act.

Scott and his comrades found themselves consumed with musical fire, playing endlessly and recording dozens of songs. Country, blues, gospel, Dylan, rock ‘n’ roll and always the irresistible heart-and-soul pulse of Irish traditional music.

A mere handful of these extraordinary recordings eventually saw the light of day in 1988. The album opens with “Fisherman’s Blues,” Scott capturing the liberating power of the music with lines like “I know I will be loosened from the bonds that hold me fast,” and “no ceiling bearing down on me save the starry sky above.” The song’s most enduring lyric however comes at the moment that words become insufficient for him and he lets out a delighted “whoo-hoo-hoo!”

“We Will Not be Lovers,” conjures back the mood of “Be My Enemy” with Scott warning “The touch of your flesh is tough to resist, planets collide at the smack of your kiss but you can kiss your brother.” Wickham’s fiddle tears up a storm, underpinned by Dave Ruffy’s muscular drumming. “Strange Boat” sails along on the gentlest of piano, acoustic guitars, fiddle and harmonica. It’s as much of a manifesto for this new Waterboys music as “The Big Music” was four years previously.

That music makes a brief return on “World Party,” which includes Karl Wallinger in the compositional credits. Lorimer’s trumpet makes it’s familiar impact, along with a host of voices including The Abergavenny Male Voice Choir! Van Morrison’s “Sweet Thing” marks the first appearance of a cover version on a Waterboys album. It’s far more than that however, as the four Waterboys (and drummer Peter Mc Kinnery), soar and dive in musical conversation between guitar, fiddle, bass and mandolin. “Jimmy Hickey’s Waltz” is a delightfully whimsical and authentic-sounding tune in honour of a Waterboys crewmember. Performed live by the “main four,” it features Scott occupying the drum stool (!), and a tempo set by the impromptu gathering of dancers invited in for the recording.

“And A Bang on the Ear” sees Scott casting a rueful and affectionate eye at his list of past lovers. There are some unforgettable lines among the clear economy of language here. Try these for starters -“Nora was my girl when I first was in a group. I can still see her to this day, stirring chicken soup.” “It started up in Fife; it ended up in tears.” In the final verse Scott refers to his current partner as “my woman of the hearth fire, harbour of my soul.”

“Has Anybody Here Seen Hank?” another old-time country waltz, pays homage to Hank Williams, the original honky-tonkin’ lovesick blues man. “When Will We Be Married?” is the result of Scott improvising a lyric over the “Ten-penny bit” jig. The simple, repeating lines of the song suggest that Scott’s looked deep into the well of traditional Celtic music and seen the face of the blues reflected there. Casual listeners often remark that Fisherman’s Blues is an “Irish,” record, with no blues at all. They’re looking in the wrong places, for while there’s certainly nothing here to suggest the Mississippi Delta, the blues can be as Irish as cabbage and spuds. Not convinced? Listen to an uilleann piper, a sean nos singer, an emigration ballad or a slow fiddle air. Now listen to the next song, “When ye go away” with its tale of sorrow at parting. The stark, confessional honesty of the line “I will cry when you go away,” is nothing but the blues, as is the slide mandolin. Charlie Lennon wrote the magnificent “River Road Reel,” which lives up to it’s name as it rolls and twists across the songs musical landscape.

The next track is a brief, twice-round jig called “Dunford’s Fancy.” Performed by Wickham (its composer) on fiddle and accompanied by Brendan O’Regan on bouzouki, it’s a spot of melodic light relief before “The Stolen Child.” Setting the words of great poets to music was something of a fad amongst underground folk-rock acts during the early seventies. Most of these attempts succeeded only in holding up the ridiculous vanity of their “composers” to public ridicule. Scott’s decision to tackle Yeats, (in Ireland!) was truly audacious. If he was going to make a pigs ear of this one, then he’d better have those airline tickets handy. Mercifully he did no such thing, wisely recruiting the traditional Gaelic singer Tomas McKeown to deliver the spoken words while the Waterboys perfectly capture the nameless music of Yeats’ Celtic Twilight.

So what, if anything, did Fisherman’s Blues actually achieve? (apart from confusing the hell out of a handful of critics.) It turned a significantly large number of rock fans on to folk music and jogged a whole legion of folkies out of their lethargy. It boosted sales of W. B Yeats books overnight, (some Dublin wits speculated that the W. B. stood for Water Boy) provided the buskers of Europe with their very own “National” anthem, and struck the match that lit a million festival camp fires. Ireland adopted Mike Scott as a National Hero and gave him the keys to another Big Music. With Fisherman’s Blues Scott unlocked it and placed it in the hearts and hands of everyone.

- Further reading – W. B. Yeats’ The Poems.

- Further listening – De Dannan’s How The West Was Won, The Beatles’ The Beatles, Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, Bob Dylan & The Band’s The Basement Tapes, and Hank Williams’ 40 Greatest Hits.

By the time Room to Roam appeared the Waterboys were firmly ensconced in the Wild West (of Ireland), and had become the magnificent seven: Scott, Thistlethwaite, Wickham, Hutchinson, Blakey, Bridgeman and Shannon. Noel Bridgeman’s reputation as Ireland’s finest drummer was established as far back as 1970 when Skid Row (featuring teenage guitar hero Gary Moore), called “time,” on the show band-era with their wildly inventive and exotic progressive rock. The recruitment of accordion and fiddle player Sharon Shannon was a masterstroke. In his book Notes from the Heart P. J. Curtis describes his first impressions of Shannon, playing in a session at McGann’s pub, Doolin Co Clare: “Sharon’s sense of sheer delight and joy as she played was infectious – I truly felt that here was one of those rare persons gifted beyond normal, a person truly touched by the light.” Her effect on the Waterboys was equally electrifying. The band lit-up like Disneyland at Christmas and produced what remains (in my humble opinion) the ultimate feel-good album.

By the time Room to Roam appeared the Waterboys were firmly ensconced in the Wild West (of Ireland), and had become the magnificent seven: Scott, Thistlethwaite, Wickham, Hutchinson, Blakey, Bridgeman and Shannon. Noel Bridgeman’s reputation as Ireland’s finest drummer was established as far back as 1970 when Skid Row (featuring teenage guitar hero Gary Moore), called “time,” on the show band-era with their wildly inventive and exotic progressive rock. The recruitment of accordion and fiddle player Sharon Shannon was a masterstroke. In his book Notes from the Heart P. J. Curtis describes his first impressions of Shannon, playing in a session at McGann’s pub, Doolin Co Clare: “Sharon’s sense of sheer delight and joy as she played was infectious – I truly felt that here was one of those rare persons gifted beyond normal, a person truly touched by the light.” Her effect on the Waterboys was equally electrifying. The band lit-up like Disneyland at Christmas and produced what remains (in my humble opinion) the ultimate feel-good album.

The non-stop, free-wheeling nature of the music creates the impression that the band couldn’t possibly hope to capture it all on one album, but went ahead and did it anyway. Whereas The Waterboys contained eight tracks, this one’s got seventeen, several of them merely snippets and fragments, like an all-night session condensed down to forty-three minutes.

This is captured perfectly on “Song from the end of the World” (which follows the brief opener “In Search of a Rose”) in the lines “furious music from an open door, the sound of feet beating on a stone floor. Always the wind, always the form of an elder God, hooved and horned.” Scott has found his Pagan place and he’s flying on it’s ever-present, ancient magic. “A Man is in Love” is a perfect distillation of the euphoria of new love. Scott sings about the “man,” in the third person until the very last line when his voice drops to a confessional whisper for “a man is in love, and he’s me.” This admission unleashes a surge of joy and relief in the form of “Kaliope House,” the infectious and (now) ubiquitous jig composed by Dave Richardson of the Boys of the Lough.

“Bigger Picture,” presents a quietly contemplative Scott, a different side to the character that we’ve become accustomed to, the restless artist howling his rage and boarding the train without a backwards glance. The vast rural landscape has brought out a sense of “belonging” in him: “my time is long but not forever, my moods are the changing wind and weather.” The piano, drums, guitars and harmony vocals evoke memories of Scott’s influences before the fiddles and flutes came along, sounding uncannily like McCartney, Starr, Harrison and Lennon. “Natural Bridge Blues” is a piece of joyful instrumental hokum with what sounds like a family celebration going on behind it.

In the midst of all this cosy jollity however, we get “Something That Is Gone,” where Scott cautiously allows the restless artist back out for a bit of self-examination. “something that I cradled in my hand, something rather special that pertained to all my plans. I’m left here wondering what on earth it was, something that I lost.” “A life of Sundays,” re-affirms the album’s predominately optimistic mood with Scott singing “it struck me (as) sad and strange, all that ever stays the same is change – I wandered wayward as a restless wave spanning from here to yonder – most spectacularly saved!” The subsequent permanence of this “salvation,” is perhaps sub-consciously hinted at in the song’s final verse: “it’s fine to be in your company, funny to be in your day, a miracle to be with you, glad to be going your way,” which suggests that Scott’s wayward wanderings aren’t as “over,” as he asserts.

“Islandman,” is a witty and clever aside in which Scott compares himself to (what Robin Williamson termed) “the green islands of the grey North Sea.” “Scotland is my dreaming head, Ireland is my heart.” “The Raggle Taggle Gypsy,” is a traditional song that exists in a multitude of versions around the world. This is a rocked-up version of the Planxty version of the John Reilly version (!) and if you ‘d like to hear it, then go and sit in any London-Irish pub with a juke box for half an hour or so. “How long will I love you?” is unashamedly sentimental, the answer to the question being “as long as stars are above you, and longer, if I can.” “Upon the Wind and Waves,” written and sung by Wickham is a little song-picture of a boat trip made with some good friends (Greenpeace activists, though the song doesn’t make that explicit.)

“Spring comes to Spiddal,” delights in the sudden warmth and activity of a place preparing to welcome its annual influx of visitors. “The roadside teahouse door is wide open, a sign on the wall says American also spoken – a tourist with a telescope and a funny looking German bloke, and a billy goat all invoke the Summer soon to bloom.” Funny, affectionate and perceptive, the song utilises the same skills that Scott brought into play on “Bang on the ear,” and applies them to an experience based in community, rather than personality — in other words, a folk song, and a good one too.

“The Trip to Broadford,” is a waltz-time showcase for Shannon’s dancing, giggling accordeon, and is therefore worth the price of the album in itself. (Remind me, have I ever mentioned that I quite like her music?) “Further up, Further in” is a dream song, as Scott (propelled by Bridgeman), soars and tumbles through a kaleidoscope of arcane archetypes and images drawn from mythology and the tarot. A short eavesdrop on a pub session, and we’re transported to the fairground that graces the album cover with “Room to Roam,” a poem by George Macdonald set to music and sung by a chorus of the band and friends. As a final flourish there’s a short, celebratory burst of “The Kings of Kerry,” a slide (regional variation of a jig), composed in honour of Seamus Begley and Stephen Cooney.

Room to Roam divided critical opinion like no previous Waterboys album. Most of the rock brigade decided that Mike Scott had completely lost the plot, along with his anger and electric guitar. Other observers held unrealistically high hopes for it, greeting its mixture of traditionally-based melody and wide-eyed lyrical wonder as the starting point for a new, improved flower-generation. (Donovan was reported as going into raptures at seeing this band, gushing excitedly about a perfect union of Planxty and The Beatles.) The rest of us, caught up in the moment, just wanted it to go on forever. Let’s sing that final chorus of “Room to Roam” one more time. “You go yours, and I’ll go mine, the many ways we’ll wend.” Sounds like that train’s a -rolling again …

- Further reading – A. E.’s The Candle of Vision.

- Further listening – Sharon Shannon’s Sharon Shannon and Seamus Begley & Stephen Cooney’s Meiteal.

The Room to Roam band couldn’t go on forever, and quickly evaporated. Sharon Shannon’s eponymous debut album was released and almost immediately established her as Irish music’s biggest and brightest star. When she formed her own touring band it included Trevor Hutchinson. Blakey and Bridgeman left; the latter’s departure apparently triggering Wickham’s decision to join the exodus. With Wickham gone, the “Irish” Waterboys simply ceased to be. In an interview with Folk Roots magazine, Scott stated that he’d made a firm decision to not replace Wickham with another fiddler, as to do so would be to close the door on Wickham. The fiddler meanwhile cropped up on various recordings of traditional music and formed the endearingly quirky Connacht Ramblers.

The Room to Roam band couldn’t go on forever, and quickly evaporated. Sharon Shannon’s eponymous debut album was released and almost immediately established her as Irish music’s biggest and brightest star. When she formed her own touring band it included Trevor Hutchinson. Blakey and Bridgeman left; the latter’s departure apparently triggering Wickham’s decision to join the exodus. With Wickham gone, the “Irish” Waterboys simply ceased to be. In an interview with Folk Roots magazine, Scott stated that he’d made a firm decision to not replace Wickham with another fiddler, as to do so would be to close the door on Wickham. The fiddler meanwhile cropped up on various recordings of traditional music and formed the endearingly quirky Connacht Ramblers.

Thistlethwaite made his exit too, and released a fine blues album Aesop Wrote a Fable which included seven former Waterboys (and ex-Stone Mick Taylor). The release of The Best of the Waterboys ’81-’90 marked the end of Scott’s contract with Ensign/Chrysalis.

Once again Scott found himself at the first line of that first review of the first album. “The Waterboys are Mike Scott…” With nothing left to stop him he got himself a plane ticket to New York city, where he wrote and recorded Dream Harder.

Anyone who expected Scott to lick his wounds quietly on this album received a rude awakening with (literally) the first note of “The New Life,” which was the loudest sound yet to bear the Waterboys name. Scott’s singing with a swagger from the song’s opening line “I’ve burned my bridges and I’m free at last, all my chains are in the past.” Meanwhile, he rediscovered the electric guitar with a vengeance, unleashing stinging lead lines over the tumult created by a crack team of New York’s finest sessioneers.

Perhaps surprisingly Glastonbury Song looks back, rather than forward as Scott appraises his current situation from the literal and metaphoric signposts on his journey thus far. This is further emphasized in the CD booklet which contains background maps of Ireland, Edinburgh, Greece, Glastonbury and New York: all of which seem to have acquired the status of “sacred sites,” in Scott’s life. “Hey! I’ve just found God where he always was.” He’s come to the conclusion that all roads lead within, a theme that he warms to in Preparing to Fly where he informs us that “I shed some weight, changed my address, I haven’t felt so great since I first went West.”

By now one begins to realise that this album isn’t so wildly different from its predecessor after all. The landscape hasn’t so much changed from Spiddal to New York, as from the outer world to the inner. Removed from Ireland’s wild, natural environment Scott seems to have sought the same inspiration through personal techniques like meditation, breathing and dream analysis. Lo and behold, he’s brought back to a familiar, “lightning-eyed” face on “The Return of Pan.” “Some say the gods are just a myth, but guess who I’ve been dancing with.”

“Corn Circles,” addresses the curious crop formations that provide a constant topic of summer conversation in rural English pubs. Scott muses on a variety of popular explanations “pixies, witches, hoaxers, take your pick,” and suggests, “throw a few theories out there, see what sticks!” During the song’s fade we hear Scott (as a taxi driver), muttering “I had that Dalai Lama in the back of me cab once….” Amazingly (or perhaps not!) few reviewers seemed willing to believe that the song was deliberately humorous, and still fewer that Scott could be capable of laughing at himself.

“Suffer,” is the album’s spleen-venting song, with Scott dishing it out like Dylan on “like a Rolling Stone,” – “you used the tongue of love like a boxer uses fists – I’m going to write you out of my life and shut the door.” The song’s buoyed along on the kind of reggae backbeat which would make it a guaranteed floor-filler at a wedding disco if it weren’t for the lyrics… perhaps that’s the point.

“Winter, Winter,” is a very short, minor key verse which goes straight into “Love and Death,” Scott’s second recording of Yeats’ poetry set to music. “Spiritual City,” is the sound of Scott’s deep-seated natural sense of humour conversing with his Quaker-like openness to accept truth wherever it may be found. The end of the song features the dulcet spoken tones of fellow-Scot Billy Connolly espousing a few pearls of his own wisdom. “Wonders of Lewis,” is a simple, heartfelt testament to the Scottish Isle and it’s standing stones. Scott’s mind, he informs us, is “blown.”

There’s no such easy-going, pastoral mellowness on the following song. “The Return of Jimi Hendrix,” a jagged, electric dream-song spoken across rattle bone percussion, overdriven guitar amplifiers and the apocalyptic drumming of Jim Keltner. It’s a neat twist to name Jimi’s song as the twin to “Pan.” Perhaps they’ve both become symbols of long-gone golden ages and dismissed as myths in the modern world. It would seem that Scott, (who elsewhere declares that “I’ve come around to the ancient ways,”) hasn’t lost his abiding belief in the redemptive power of rock ‘n’ roll either.

“Good News” finishes the album with it’s declaration that “a brand new age is already here.” Scott is bursting with optimism, describing himself as one of many “preparing for birth-in step with the stars, in league with the land, a functioning part of the master’s plan.” A piano swings jazzily, a saxophone sounds the heavenly horn and it’s all over.

How best to sum up Dream Harder then? It was hailed as a return to “the true Waterboys sound,” by some journalists who heard the electric guitars and simply breathed a sigh of relief. Surely, they reasoned, they could now dismiss the two previous albums as Mike Scott’s postcards from some aberrant holiday romance. They were missing an important point, which is that Mike Scott’s music, (irrespective of the musical style that’s inspiring him at the time), is only ever the vehicle that carries the lyrics. Viewed in that context, Dream Harder is a natural successor to Room to Roam

To my mind, Dream Harder is the loudest, funniest, most intelligent and exciting record that ever genuinely fitted the category of New-Age Music. Something unique then, wouldn’t you say?

- Further reading – George Trevelyan’s A Vision of The Aquarian Age, Dion Fortune’s Glastonbury: Avalon of the Heart.

- Further listening – Kate Bush’s The Dreaming, and Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland.

There’s no doubt that New York provided Scott with the studios and musicians to create a supercharged rock album with Dream Harder. Getting the city to yield him a touring band was a far more difficult task, which eventually proved impossible. Even if he’d found a group of available musicians worthy of bestowing the Waterboys name on, it’s unlikely that they’d have shared his enthusiasm for spiritual, musical and personal development. The turning point came when Scott started reading the writings of Eileen Caddy, one of the founders of the Findhorn community in his native Scotland. Scott found himself inspired and intrigued by Findhorn’s ideals, which embrace ecology, spirituality, organic food production and cooperation.

There’s no doubt that New York provided Scott with the studios and musicians to create a supercharged rock album with Dream Harder. Getting the city to yield him a touring band was a far more difficult task, which eventually proved impossible. Even if he’d found a group of available musicians worthy of bestowing the Waterboys name on, it’s unlikely that they’d have shared his enthusiasm for spiritual, musical and personal development. The turning point came when Scott started reading the writings of Eileen Caddy, one of the founders of the Findhorn community in his native Scotland. Scott found himself inspired and intrigued by Findhorn’s ideals, which embrace ecology, spirituality, organic food production and cooperation.

After a series of guest visits, Mike Scott packed his bags in the big apple for the last time and made his new home in what must surely qualify as the most unlikely rock-star residence of them all. The musician credits in the CD booklet of Bring ‘Em All In read as follows. “Performed, written and sung by Mike Scott. Recorded, engineered and mixed by Niko Bolas. Produced by Scott and Bolas.”

The album opens with the title track that starts quietly (on a killer acoustic guitar riff), as Scott sings with increasing power and fervour. “Bring the unforgiven, bring the unredeemed, bring the lost, the nameless, let ’em all be seen-bring ’em all into my heart.” The following two songs deal with Scott’s emotions on revisiting his old haunts in Scotland. Both feature electric guitars providing the textures and solos. In “Iona Song,” the singer confronts guilt, anger and a sense of unworthiness brought on by the sacred isle. There’s an uncomfortable sensation of Scott seeing himself in sharp-focus due to the tangible presence of God. Only three verses long, the song is concise, eloquent and undeniably powerful. “Edinburgh Castle” is a visit to the city of Scott’s childhood, full of place-specific references, conflicting emotions and cinematic imagery. Scott reaches the conclusion that “this city once was mine, but it ain’t mine anymore.” His solution is to get back on the train (a recurring Mike Scott motif), and to let out a sigh of relief with the line “I’ve got to say it’s just totally great to back in Glasgow again!” It’s a funny and revealing line – sometimes those rock star cliches aren’t just hollow rabble rousing.

“What do you want me to do?” is, quite simply, a prayer. “I’ve got a lot of things to change, a whole man to rearrange, and if you’ll show me how I’ll begin right now. What do you want me to do Lord?” There’s no musical histrionics here, just a simple, strummed guitar and a bit of harmonica. It’s always astonishing to witness the effect that this song has on live audiences, people of many faiths and none. In opening himself up completely, Scott communicates an honesty, vulnerability, open-heartedness and courage that utterly defeats any residual sneering or mockery among his listeners.

“I know she’s in the building,” finds Scott “inflamed with love and joy,” by a woman, a fellow-resident at Findhorn. It’s an aspect of communal living that’s often overlooked, (or the subject of prurient speculation), but Scott’s in no doubt that he’s fallen passionately in love. The lack of privacy creates an almost unbearable tension “I listen for each step or voice that passes by my door. I can feel the raw excitement bursting in my chest.” It’s an intoxicating, explosive cocktail of sex and spirituality which invokes “King Pan,” an oft-used but wholly appropriate Scott metaphor for this ecstatically deranged state of mind. It’s a rocking, euphoric performance that brings a sweat out in the listener!

“City Full of Ghosts,” refers to Dublin, scene of many past glories in “a time when I still had the power.” The city’s “ghosts,” appear in many forms. There’s the sadness of broken friendships and the break-up of a band, but there’s affection and laughter too. “Dublin is a city full of humour; Dublin is a city full of wit. Dublin is a city full of buskers, playing old Waterboys hits.” “Wonderful Disguise,” is a song that examines how our perceptions of each other are informed by how we choose to portray ourselves, rather than by who or what we really are. There’s a great deal of insight and perception bubbling through the toe-tapping tune and superficially humorous lyrics. Having observed the “disguises,” of a colourful cast of third-party characters, Scott turns to himself for the final verse, “Stood in front of the mirror all alone – looked at the face I’ve always known. It was a wonderful disguise.” The archetypical figure of “the wise fool,” is, like Pan, a recurring image in Mike Scott’s work. With this song, the preceding “City Full of Ghosts,” and his approach to performances, he became the living embodiment of the ideal.

“Sensitive Children,” is a plea for unconditional love towards the child who appears to be a “strange little alien, acting like she don’t belong.” It’s reminiscent of Bob Dylan, both musically and in the simple poignancy of the lyrics. “Learning to Love Him,” is a progress report on the process of healing that started in the emotional maelstrom of “Iona Song.” The song’s in 3/4 time, an old-time country melody with an accompaniment so sparse you can hear Scott’s fingers tapping on the top of his guitar. “She is so Beautiful” brings us back to the woman who inspired “I know she’s in the building.” She’s become “the most beautiful soul I ever have met in this life,” and Scott claims to have “no words to describe the way she makes me feel inside.” He does however, and they’re incredibly moving. The song ends with the heartbreaking realisation that the singer can’t remain at Findhorn forever; “I don’t know what I’m going to do when I leave – except grieve.”

The previous track’s lingering, sad aftertaste is swept away by the rolling wave of “Long Way to the Light.” This recounts the whole, unlikely adventure story of the man who set off for New York to reclaim his place in the upper echelons of the rock ‘n’ roll pantheon and somehow ended up in Findhorn. It’s a song worthy of the tale, brimming with tremendous lyricism and a musical wallop that sustains the listener from beginning to end. Among Scott’s many wry musings there’s this one, “if you want to give God a laugh – tell him your plans!”

The album closes with “Building the City of Light.” The strident electric guitars and declamatory lyrics hark back to “New Life,” the opening song on Dream Harder It seems that Scott’s Findhorn experience has only brought him full circle. Has he arrived back at the absolute certainties and invincible self-belief of yore? No, he’s grown and changed here, and the “wise fool,” has been let out to work and play on this song. The final lines are, “All may change in the blink of an eye. All may change in the blink of an eye.”

Bring ‘Em All In was lazily (and inevitably) dismissed by many as “a religious album,” and mentally filed alongside Bob Dylan’s “Slow Train Coming” (itself a much better record than it’s often given credit for). It’s a comparison that doesn’t hold water. Whereas Dylan preached, Scott speaks his truth. There are very few artists who manage to produce an album that is genuinely ageless and timeless. The ones that spring to mind include Nick Drake, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, and that man Dylan (again), all of whom employed the same basic guitars, piano, and harmonica approach. Never in fashion, never goes out. Like those examples, Bring ’em all in could (and should) be “discovered,” by subsequent generations for decades after it’s time of release. It could, conceivably, even come to be seen as something of a “masterpiece.”

While Bring ‘Em All In was an object lesson in the art of understatement, it’s successor Still Burning marched to the beat of a very different drum. The clues are there before the CD is even in the player. The cover of the first solo album carried a head-on portrait of Scott, face half obscured by his hand and his right eye looking directly towards the viewer. One this one he’s framed almost diagonally, shirt open, his eyes concealed by the biggest and blackest of rock-star shades. Then there’s that title Still Burning, with it’s implicit air of defiance.

While Bring ‘Em All In was an object lesson in the art of understatement, it’s successor Still Burning marched to the beat of a very different drum. The clues are there before the CD is even in the player. The cover of the first solo album carried a head-on portrait of Scott, face half obscured by his hand and his right eye looking directly towards the viewer. One this one he’s framed almost diagonally, shirt open, his eyes concealed by the biggest and blackest of rock-star shades. Then there’s that title Still Burning, with it’s implicit air of defiance.

The musician credits read like a who’s who of rock session big guns. Chris Bruce (electric guitar), Jim Keltner (drums), Pino Palladino (bass), James Hallawell (Hammond and Wurlitzer organs), The kick horns, The Memphis horns — superlative players each and every one of them, but names that you’d expect to appear on recordings by the likes of Rod Stewart rather than Mike Scott. Add in the string orchestrations, keyboards and backing singers, and you get the feeling that somebody (whether the artist himself or someone at Chrysalis) had decided that it was time for Mike Scott to deliver another “hit.”

The horns are well to the fore on “Questions,” a song with a strong verse – chorus – middle section structure. Among the questions asked is “who on earth am I meaning when I say me?” Perhaps Scott is experiencing some difficulties with adjustment back to the “mainstream,” market. That speculation is reinforced by the following “My Dark Side,” something that Scott “can’t show to anyone but you, my close and intimate one.” He’s canny enough to pre-empt this kind of analysis, with the warning “drop the jury, leave ’em home, I won’t be judged, only known.”

“Open,” is a simple and effective litany of receptivity and acceptance. Open to change, adventure, love, miracles, laughter, service, joy, beauty – it’s a song from the same place as “Bring ’em all in.” “Love Anyway,” and “Rare Precious and Gone,” were the two songs marked for potential hit single status. They’re both fine, well-crafted songs (and streets ahead of most of the competition), but certainly don’t match the standards that Scott previously set with “The Whole of the Moon.”

In “Dark Man of My Dreams,” Scott’s dreams are haunted by meetings with his father. It’s a powerful and disquieting song and one of the album’s stand-out tracks. “Dark man of my dreams, this information you keep – will it frighten me, enlighten me or make me weep?” The line “you ain’t him,” suggests a sly reference to “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” but could equally be pure coincidence…

“Personal,” is a song addressed directly to someone close. That someone may be a friend, musical collaborator or former lover, Scott’s not telling. Either way he’s reassuring them that “It’s not personal; you didn’t let me down at all. It’s how the world goes round, is all.” Whoever the “Strawberry Man,” may be, he’s not getting off so lightly. There’s a startling belligerence running through the song in lines like, “out of your van on lager and pills, placing your fist slap bang in my way,” and “I’m wondering what the hell are you for.”

“Sunrising,” reveals a lot about the motivations behind “Still Burning,” and is the song from whence the CD’s title is taken. “After all this time I’m still on the line, with a case to prove and a public to move – I’m back on show.” This was, after all, the time of “Britpop,” when anthemic, guitar-based songs by the likes of Oasis ruled the airwaves and packed football stadiums. Meanwhile the originator of “the big music” had come to be viewed as a rather marginal figure, quietly strumming his acoustic in his remote Highland hideaway. The fact that this new breed of groups were being feted for songs containing barely a fraction of the intelligence, honesty, wit and wisdom of Scott’s must have irked him considerably.

The album’s closer “Everlasting Arms” is (perhaps surprisingly), a complete return to the style and content of Bring ‘Em All In. After all the hot-shot session musicians and big production numbers, we’re left with a voice, a guitar, a piano and a harmonium with just one name in the credits – Mike Scott. The song is a close relative of “What do you want me to do,” with the singer again addressing himself directly to God. The preceding album’s prayer-song opened a window to the light. Here, the listener can feel unintentionally voyeuristic on hearing the lines “Lord raise me in your everlasting light. Awake my mind that I may understand and come to find the truth of who I am.” Still Burning isn’t a bad album, and songs like “My Dark Side,” and “Open,” amply demonstrate Scott’s uniquely versatile song writing abilities. It does, however, have something of a schizophrenic feel with it’s deeply personal, and at times, unsettling lyrics swathed in radio – friendly production and arrangements. The musicians on this CD are all such consummate professionals they could make almost anything by anybody sound fantastic. When the artist in question is Mike Scott you just wish that they’d left a bit more space for the songs to speak for themselves. Still Burning captures an artist in a period of transition, eager to re–engage with a wider audience. “I’m back on show with a mile to go, with one more mile to go.”

It’s often said (and truly) that names have power. And so it came to pass that for the first time in seven years an album bearing the name The Waterboys, A Rock in the Weary Land was released in the year 2000. The musician credits reveal some more names from long ago in Dave Ruffy, Kevin Wilkinson and Anthony Thistlethwaite.

It’s often said (and truly) that names have power. And so it came to pass that for the first time in seven years an album bearing the name The Waterboys, A Rock in the Weary Land was released in the year 2000. The musician credits reveal some more names from long ago in Dave Ruffy, Kevin Wilkinson and Anthony Thistlethwaite.

The return of the Waterboys name was heralded by a new label (RCA), whose promotional clout brought the album to the attention of folks who’d lost track of Mike Scott years ago. A review copy even found it’s way to my GMR colleague No’am Newman (in Israel), who was disappointed that it didn’t sound anything like Fisherman’s Blues. But that album was made by an artist who (having decided that “old England is dying”) had taken himself off into the “wilderness,” to grow, think and breathe. This one marks his return to the land that he left behind, specifically to London. If Mike Scott was going to take on the whole grubby, grasping, glorious business again, then he was going to position himself right in the heart of it. The cover photograph is simply fantastic. Scott is perched against a dawn sky above the silhouetted rooftops, a cockerel-man with an electric guitar, ready to wake the city with his crowing.

From the opening seconds of “Let it Happen,” it’s obvious that this isn’t going to be a case of re-treading any previous Waterboys path, nor (more importantly) does it sound like anything or anyone else. The song starts with an eerie, howling Theremin effect (a deliberate case of “Bad Vibrations?”) which ushers in a thunderstorm of raging guitars, apocalyptic drumming and seething, distorted vocals. It’s as if Scott is acting as a lightning conductor for all of the pain, anger, lies and cruelty of the city, the point of stillness in the eye of the hurricane. “Whatever needs to happen let it happen – through all I am protected, grace is effected over me.” He’s also less than impressed with the musical state of Europe’s rock ‘n’ roll capital, “A band was playing endless mindless, it was like a hooligans lament.”

This theme’s continued into “My love is my rock in the weary land.” with bands who perform by “throwing shapes, half the music is on tape.” There’s a sense of abandonment by “My mentor and champion,” who’s “busy tilting at the windmills of his stately home,” and the pain of rejection when “his accusations flow like poison from his every word.” Scott confesses that “I’m in shock, I’m on the ropes, I don’t know what’s to come.” Whoever “my love” may be, she’s the subject of an astoundingly candid and heart – felt song. “My heart would be broken but for her.”

“It’s all gone,” is the shortest song that Mike Scott’s ever recorded: “it’s all gone, so send the rain.” That’s it, the complete lyric. Seeing the words on a page is one thing, hearing this extraordinary solo performance is something else, and I suspect that the entire album nestles somewhere in the space between those two lines. This is the entire travelogue of Scott’s sojourn in “the weary land” reduced to its pure essence, as brief and ambiguous as a postcard message.

“Is she conscious?” is a response to the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. Whether that’s the whole story or it’s concealing an underlying layer of metaphor is a question that should be addressed to your local Scottologists. (They’re the small group at the table in the far corner of the Saloon bar. Ask the Dylanologists or the Bowieologists to point them out to you.)

“We are Jonah,” is a juxtaposition of oblique, Old Testament imagery and a huge chorus carried along by the most uplifting of tunes. There are some faint echoes of Neil Young (“Pocahontas,”) and The Clash (“The right profile”). somewhere in there too. When you find yourself bouncing around your room, grinning and singing “Grandma we are Jonah, rolling along in the teeth of the whale” don’t blame me if you get that strange, nervous sensation that you last felt at a Richard Thompson gig…

“Malediction,” is the song behind that striking cover image. “A black cock crows and a dead wind blows.” The fat cats of Tin Pan Alley, sleeping smugly in the knowledge that they’d chased off that persistent irritant Mike Scott, are rudely awakened by the mouse that roared. “I’m climbing down the city walls, unseen, unfussed. The sentries must be fools. I say all pleasantries are over, I say all pleasantries are past. My enemies, you pimps and thieves, prepare to meet your nemesis at last!” Er, welcome back Mr Scott…

For “Dumbing down the world,” the Mikes, Richards, Daves and Kevins who occupy the musician credits elsewhere are replaced by the cast of C. S. Lewis’ “The Screwtape Letters.” Take a bow then, Triptweeze, Slumtrimpet, Wormwood, Toadpipe, Slubgob, Slitmouth and the rest. It’s nice to hear instruments like Smurd and Fire – worm among the skinbourines, backwards guitar, sideways guitar and mock bass too. The track, by the way, was “recorded in hell.” Screwtape himself is in fine form on the lyrical front, “my thoughts are banal, like a stagnant canal.” Just as you catch yourself thinking “what an awful rhyme,” a mocking voice declares “I’m dumbing down the world and I love it!” It’s a brilliant piece of satire that, still, amazingly got dismissed as a “dumb song,” by some reviewers. Either the world really is dumbed-down to that extent or the old saying about music critics having more cloth ears than a teddy bears picnic is truer than we care to admit.

“His word is not his bond,” opens with a brief sample from a 1927 archive recording of “The Liar,” sung by one Rev. Isaiah Shelton. Somebody, somewhere, has tried to “work a number,” on Mike Scott. Whoever that con artist may have been, it was a severe error of judgement… “The Charlatan’s Lament,” is Scott in full, poetic flow; conjuring images by stretching and subverting words left, right and centre. “I swing between tears and wonder…encountered a loathly hag… can you walk a smithereen closer to me, could you love a thimbleful harder for me?”

“The wind in the wires,” is Scott appealing to his “lady,” to wake and flee with him “for mercy’s sake.” He’s feeling not just isolated (from his peers), but actually hunted, running and swimming for his life. Aware that he’s sounding paranoid, he asks “and if it’s all in our minds, well where else would it be?”

The CD closes with “Crown,” which is Scott’s most focused, and coherent “manifesto,” song yet. “I’m not through with my changes, I’ve got a long way still to run, I’m gonna play this show even if nobody comes.”

Playing shows is exactly what he consequently did as The Waterboys embarked on an ongoing global touring schedule of Herculean proportions. Once again the Waterboys is more than a name, it’s inarguably a band. Keyboard player (and multi – instrumentalist) Richard Naiff came in for the album sessions and has stayed ever since. An award-winning classical organist with an encyclopaedic knowledge of (Brit-punks) The Damned may sound like an unlikely combination, but Naiff’s exactly the kind of brilliant musical polymath that Scott thrives with in his ranks. The other core member of the current Waterboys is none other than Steve Wickham, returned to the fold after a decade’s absence. Scott is, was, and ever shall be the head of the Waterboys but for many long-term fans, Wickham represents a significant part of the bands heart.

This Waterboys’ line-up is probably the most versatile and resilient yet, and the band are currently operating in two formats. The core trio performs in an acoustic setting and can be seen at the larger UK folk festivals this summer. With the addition of a drummer and bass player, they’re a powerhouse rock ‘n’ roll band, more than capable of holding their own with the likes of Neil Young and Crazy Horse.

A Rock in the Weary Land is the sound of Mike Scott taking his raw rage, pain, anger and bewilderment, and forging them in the heat of noise and electricity. By the time that the songs left the anvil, they’d become a living-breathing band and evidence of feats of transmutation like that haven’t been seen in these parts since Blodeuwedd was formed out of flowers in The Mabinogion. Whatever the next album sounds like, it won’t be from Mike Scott in “The Weary Land.” He’s been to that place, survived, grown stronger and left it behind as The Waterboys. Names have power.

- Further reading – C. S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters.

- Credit for all biographical and chronological information should go to Peter Anderson for his Mike Scott/Waterboys biography originally published in Record Collector in the June 1991 issue; Mike Scott for the chronology at his website.

- Another view of A Rock In The Weary Land can be found here.

- Factual inaccuracies, ridiculous assumptions and contentious opinions are all the authors’ own work.

- The suggestions for “further reading” and “further listening” are included purely because they popped into this reviewer’s head at the time of writing. Some are obvious and inarguable; others may turn out to be red herrings.