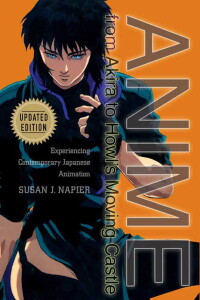

Napier, a professor of Japanese literature and culture, originally wrote this intriguing analysis of anime in 2001. Following the worldwide critical and commercial success of Miyazaki Hayao’s Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle movies, she decided to revisit and revise Anime, updating it with some more recent titles. Why, you might ask? After all, they’re just cartoons, right? If you’ve never been exposed to Japanese animation, you might well be tempted to ask just that. And indeed, Napier herself might’ve asked just that years ago, before she’d been introduced to Akira, the post-apocalyptic anime movie that changed her outlook on anime.

Napier, a professor of Japanese literature and culture, originally wrote this intriguing analysis of anime in 2001. Following the worldwide critical and commercial success of Miyazaki Hayao’s Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle movies, she decided to revisit and revise Anime, updating it with some more recent titles. Why, you might ask? After all, they’re just cartoons, right? If you’ve never been exposed to Japanese animation, you might well be tempted to ask just that. And indeed, Napier herself might’ve asked just that years ago, before she’d been introduced to Akira, the post-apocalyptic anime movie that changed her outlook on anime.

The reasons Napier provides for studying anime are manifold. First and foremost, “For those interested in Japanese culture, it is a richly fascinating contemporary Japanese art form with a distinctive narrative and visual aesthetic that both harks back to traditional Japanese culture and moves forward to the cutting edge of art and media. Furthermore, anime with its enormous breadth of subject material is also a useful mirror on contemporary Japanese society, offering an array of insights into the significant issues, dreams, and nightmares of the day.” Napier also points to the global commercial and cultural influence of anime.

Ultimately, the main focus that Napier takes to tackling her study of anime is three particular areas: the apocalyptic (both widespread and the intimate), the festival (in the sense of change) and the elegiac (as in loss or grief). And it’s this point of view that drives her research and findings.

The meat of the book is divided into three sections: “Body, Metamorphosis, Identity,” “Magical Girls and Fantasy Worlds,” and “Remaking Master Narratives: Anime Confronts History.” In the first section, she tackles the issue of how the body is represented in anime, from teens who switch genders or turn into monsters to teens who pilot giant mechas. She also discusses the changing role of male characters in anime and devotes an entire chapter to the body in pornographic anime (or, as she notes, horror occult anime featuring sex, as that’s what she focuses on). In the next section, she reflects on some of the roles of female characters in anime (though, as I’ll point out again below, predominately in anime aimed at a male audience or for all audiences). And in the final section, she examines several anime that look back on Japan’s past, particularly World War II.

Napier consistently uses a professional, scholarly tone throughout the volume. At no point does she ever slip across the line into fannish enthusiasm, though it’s apparent that she does seem to enjoy the anime works she studies. Her writing remains accessible to fans, though, and she keeps scholarly terminology to a minimum (though she’s excessively fond of the word “defamiliarize”), carefully defining all Japanese terms. She’s clearly well-versed in Japanese culture and makes insightful connections. Readers may not always agree with her conclusions (I did not – I would argue, for example, that Utena did not willingly participate in her false reality, for she did not even know it to be a false reality), but her essays will at least provoke thoughtful discussion. Beware! There are spoilers to be found, so if you have not seen a movie or series, you may want to skip some of the sections.

It is interesting to note, that with very few exceptions – Utena, and passing references to Sailor Moon, mostly – Napier focuses almost entirely on anime that is marketed for boys (shounen) or for everyone (Miyazaki’s works tend to defy genre). She also barely touches the tip of the iceberg, mentioning a handful of titles, mostly considered classics (even the hentai) or produced and written by masters, when there is a vast amount more out there. While she does analyze a few recent titles – Inuyasha, Wolf’s Rain, Haibane Renmei – most are relegated to the introduction. To be fair, she does mention that there is much more anime out there, but Napier really should, at some point, revisit this volume and expand it to cover a broader spectrum of anime works, especially since of the works she discusses are now truly classic, at twenty years or older. It would also be helpful if a few more colour plates were included, since there are only a handful, and they are somewhat old and grainy.

This is a well-written scholarly book about a cultural import that’s still largely misunderstood by non-fans in the U.S. While it’s perhaps not a good introduction to what’s available or a “What should my kids watch?” guide, it does make a good answer to the question “Why anime?”

(Palgrave Macmillan, 2005)