Judith Gennett wrote this review.

Judith Gennett wrote this review.

Sometime during the late nineties our radio station in Texas received an archival rembetika CD from Rounder Records. It all sounded Greek to me, but then I began to read the lyrics. Pick-pockets, jail, knife fights, hash dens … classic rembetika was, as explained in the liner notes, the popular music of the Greek Underworld. Whoa!

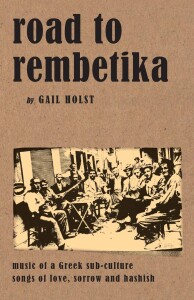

What exactly is rembetika? Why did the underworld exist? Road To Rembetika provides the answers. You can find a good synopsis of the story and, suspiciously, of Holst’s book by reading the rembetika section in the Rough Guide To World Music, a correlation that was not the case with Tim Rice’s book on Bulgaria, May It Fill Your Soul. After an abortive Greek attempt to recapture Constantinople in 1922, Turkey sent its copious Orthodox and therefore “Greek” population packing in a frightful exodus, swamping Mother Greece. Hash dens, or teke, were common in the culture of poverty that developed among the refugees, not surprising as smoking dope had been relatively legal back home in Turkey. Men would gather around the narghile, puff dreamily, and someone would pull out a little baglama or a bouzouki, and — voila! — rembetika! The roots of this rembetika were in jail songs and in the more sophisticated music of Turkish-style Cafe Amans. The spirit was not unlike that of American urban blues.

Holst’s eighty-two pages of text follow rembetika from its wonderful early days in the underworld, through the golden era with familiar stars like Markos Vamvakaris, through persecutions and the war years in which rembetika lyrics carried political satire. After the war, rembetika became respectable and so did the lyrics, as fashionable western European scales and harmonies (as opposed to the eastern modal taxima) crept in like a plague. It became common for women, once the lyrical bane of rembetika performers, to sing. Finally, in the sixties, the culture turned to cafe plate-smashing extravagance and the music to muddy electric bouzoukis.

The most striking property of Road To Rembetika is not that Holst gives a respectable history of rembetika, but that she does so with the passion and quirky writing style of an Australian woman enraptured with the Mediterranean, suspended between two worlds. Dr. Holst is an adjunct professor in Classics at Cornell, and, though her prose is adequately scholarly, you could imagine her writing travel articles about cafės in southern France. “Rembetika is not a high art form, and it doesn’t seem to me advisable to approach it from too academic a standpoint,” she explains in the introduction. This path has allowed her to follow her perferred directions. She has included what anecdotes she likes without overwhelming lay persons with jargon and esoteric theory. At times, however, her writing is reminiscent of the lyrical translations now so fashionably satirized in CD booklets — for instance in a teke scenario: “Hey Mikhaili, have you heard about the stuff Uncle Yanni’s brought in from Itea? It’ll send you off your head with two puffs they told me.”

Holst, who lived for several of the hippie era years in Greece chasing rembetika, is enchanted with the people as much as with the music. The scenario above is part of a chapter that outlines the colorful life of bouzouki player Markos Vamvakaris, including his association with the great supergroup that included Artemis, Markos, Batis and Stratos the Lazy. Artemis died at twenty-nine from drugs, lying in the street holding his bouzouki; jazz fans will find that Artemis’ brief life paralleled that of American musicians like Bix Beiderbecke. Near the end of her book, Holst also tells the stories of three “ordinary” people, now in their sixties, who were part of the rembetika world, including her bouzouki instructor on the Isle of Aegena, Thanassis Athanasiou.

As in many ethnomusicology books, only one small chapter is devoted to the music itself. Holst tells about the instruments and shows illustrations of vintage bouzoukis. She briefly explains the rhythms and the dances that go with the rhythms … usually a 9/8 zembekiko but sometimes in other odd or even metered rhythms. She talks very briefly about the “roads” … western modes or eastern taxima … followed by the bouzouki player to make rembetika tunes. But, interestingly, Holst devotes eighty pages to lyrics, giving transcriptions in Greek letters and translations into English. Though this is best thought of as a resource, it is useful to see how the topics changed with time. “We pulled three knives but they did us no good,” “From sniffing it up, I went on to the needle,” and “First light up my narghile so I can smoke and turn on” give way to the wartime “It’s petrol and kerosene we’re after,” to be superceded by 1950’s “Maybe you’ve loved and been cheated.” The love lyrics were always in rembetika, but by 1950 there is almost nothing else to quote.

At the end of the book, Holst gives a two page bibliography, much of it in Greek. Following this is a nine page discography; in this case everything is Greek except for four American albums. Since the time this book was written, some additional recordings have been made, so now would be the time to pick up the Rough Guide.

Recommended for people who want to read the seminal book on rembetika! If you’re interested in a briefer sketch of rembetika from someone with a different writing style, check out this page.

(Denise Harvey, 1974; third edition 1983; reprinted with amendments 1994)