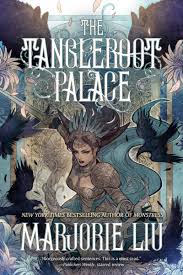

Marjorie Liu’s The Tangleroot Palace collects a number of the author’s shorter works, including the one that gives the volume its title. Most of them fit well into the wheelhouse of the woman who gave the world Monstress, and her skill is apparent.

Marjorie Liu’s The Tangleroot Palace collects a number of the author’s shorter works, including the one that gives the volume its title. Most of them fit well into the wheelhouse of the woman who gave the world Monstress, and her skill is apparent.

The introduction itself gives a fascinating glimpse into the mind of the author, as she describes the fact stories tend to slip largely away from her once she has finished writing them. It is not a phenomenon you will hear a great many authors describe, though inquiry suggest its more common than one might suspect.

“Sympathy for the Bones,” which opens the collection, feels like a classic fairy tale told in first person. It features a girl who loses her parents, a witch, dark magic, and the power of love. Mind, those take very different forms from what many readers would suspect.

Truly as an opener “Sympathy for the Bones” is an excellent choice. It features an assortment of elements that are truly familiar to readers, allowing them to clearly see just how Marjorie Liu uses them to tell a tale. In this case the themes of loss, abuse, risk, and improvement are all clear while the atmosphere remains something familiar to anyone who ever read Grimm.

The titular story is a long piece. A novella divided into chapters, it centers upon a girl called Sally, a princess in a kingdom that is in a particular kind of peril. There have been steady and increasing encroachments upon their borders, and it looks as though it will not be long before the kingdom is attacked and conquered from without. Her father makes clear that he sees forcing her to marry a barbarian warlord with a number of horrifying titles is the only solution.

Sally is naturally appalled, and runs away. She seeks out the Tanglewood, a place to the south which is often considered completely and utterly haunted and unlivable. She meets brigands and adventurers, actors and wild girls on her journey, seeking out a way to make her life without submitting to a disgusting fate. There is a strong theme of feeling and being trapped, and how the two are often one and the same.

Indeed, this particular story is light on detail and heavy at the right perspective moments, serving as an excellent reminder of that particular art form and its advantages, when many authors would have the first instinct to stretch such a piece to novel length. Such stretching often works, but can also ruin some of the delicate balance of a short narrative.

After each story is a small snippet in which the author recounts what she can of the circumstances under which it was written. In light of the introduction, these already interesting paragraphs will become fascinating to many readers.

Overall Marjorie Liu’s The Tanglewood Palace is a nice collection, and features excellent stories by an author who knows her craft well. It is of course easy to recommend to fans of her work; however it can be heartily recommended to those with only a vague curiosity about her. Stories in this volume evoke everyone from William Goldman to Tanya Huff, from Hayao Miyazaki to Kevin Smith, and do so with almost poetic ease.

(Tachyon, 2021)