Michelle Erica Green penned this review.

Michelle Erica Green penned this review.

The myth of the plucky girl with the glass slipper has suffered quite a bit of criticism in the modern era. Disney’s film about the peasant princess portrayed her as a passive pollyanna whose mice worked harder to change her fate than she did. She even became the archetype of The Cinderella Complex, a 1981 book that purported to examine women’s hidden fear of independence. The media often applies the phrase “Cinderella story” to someone who has risen from rags to riches, but it’s a favorite pastime of reporters to find the secret fairy godmothers who make it all possible; though we’re told to admire them, we’re also trained to be suspicious of people who rise to power entirely on their own initiative, especially women.

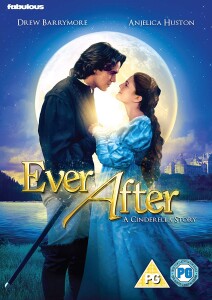

Clearly, in the era of Mulan and President Barbie, some revisions are in order merely to make Cinderella marketable, let alone a heroine. Enter the irresistible Drew Barrymore — and let me add quickly that if you don’t find Drew Barrymore irresistible, you might as well skip Ever After. She plays Danielle de Barbarac, the daughter of a Renaissance landowner whose fortunes have begun to decline, but whose values are in the right place. Auguste de Barbarac has taught his daughter literature and philosophy, giving her Thomas More’s Utopia as a gift. When he marries the widowed Baroness Rodmilla de Ghent, Auguste hopes her daughters Jacqueline and Marguerite will become companions for Danielle, but after his untimely death, Rodmilla forces Danielle to work as the family maid.

Though the story will look familiar, the characters come across as fresh and believable. Rodmilla cannot get over her disappointment at being trapped on de Barbarac’s rural estate. Her overweight daughter Jacqueline struggles for maternal and masculine approval, while slender, snobby sister Marguerite primps and preens in preparation for an aristocratic marriage. But it’s Danielle who meets Prince Henry, impressing him with her idealism and passion. He’s been groomed for a conventional reign and arranged marriage to a foreign princess. Though Henry isn’t as clever as Danielle, his sense of adventure and disdain for oppressive tradition make him likable. Danielle persuades her prince to treat servants like human beings and renews his appreciation for books so much that he wants to found a university.

By fortuitous chance, Leonardo da Vinci happens to be nearby to become Danielle’s fairy godfather when she needs a ball gown and a shoulder to cry on. This is a fairy tale Renaissance, where famous people pop up at convenient moments, modern printing presses mass-produce literature, and the daughter of landed gentry calls herself a peasant despite the “de” in her name. But it’s easy to overlook occasional anachronisms amidst the beautiful cinematography, which casts a rosy glow over pigpens and gives all servants a fresh-scrubbed country-clean image except in scenes where they’re revealing their rustic charms rolling in the mud.

Though some may be disappointed by the absence of magic in the story, it’s refreshing to see the role of spiritual advisor played by a legendary explorer who celebrates the miracles of science. The bloodiness and sense of predestination that permeate the Brothers Grimm are entirely absent. While it might be nice to have a fairy godmother in the absence of a loving parent, this lack causes Danielle to become the woman she wishes her stepmother could be — someone who tries to be kind even to the hard-hearted, who changes her fate by trying to live on her own terms.

Yet despite occasional fits of feminism, this version of Cinderella often uses its heroine as the exception who proves all the old rules. Danielle is feisty and educated and shares a sisterly bond with Jacqueline, but every other girl in the town is shown to be after one thing: the handsome prince and, of course, his money. Even women who aren’t victims of bad husbands, cruel parents or poverty won’t stop scheming, not unless they’re considered completely unpromising like Jacqueline, in which case they’re not treated much better than servants.

Danielle’s behavior toward her cruel relatives, though amusing, ultimately leaves little hope that she has real plans for a workers’ revolution. The charming twists on fairy tale convention don’t extend to the social structure. Disney fables constantly emphasize a social order, a sense that hierarchy is natural and high-born beings will rise to their proper place; Ever After suggests a similar world view, even if education and spirit offer obvious advantages over accepting socially prescribed roles for women.

Though ostensibly the film depicts the triumph of common values over aristocratic airs, it stars two Hollywood blue-bloods — Barrymore and Anjelica Huston as her wicked stepmother. They’re both great fun to watch, even if Barrymore’s adorable pout can’t compete with Huston’s towering fury. Sharp-boned Megan Dodds’ nasty sneer makes phoney-baloney Marguerite despicable, so it’s that much more satisfying when Danielle gives her a black eye. The so-called “fat” sister, played by Melanie Lynskey, is actually quite lovely, but clearly she’s being evaluated by Hollywood standards rather than those of the Renaissance.

Besides Jacqueline, Danielle is the least-anorexic ‘eligible maiden’ in the film; she looks as healthy and luscious as the apples she picks. Barrymore never disappears into the role — under the gorgeous period costumes; she’s still the pretty pixie from E.T., yet she’s a perfect blend of sweet and vivacious, a girl-next-door with surprising intelligence and an unexpected daredevil streak. As a lighthearted twist on convention, Ever After offers many pleasures and, as a fantasy of a Renaissance woman out to transform her own fortunes if not her society, it has the virtue of a happy ending.

(Fox Family Films, 1998)