To one who grew up on science fiction (and I really did — the first book I ever bought all on my own was The Big Book of Science Fiction, edited by Groff Conklin; I think that was about fifth grade. It was by no means the first science fiction book I had ever read — this was in the days before school libraries were subject to the thought police.), there are names that echo through the memory, the writers who brought visions to life that were fascinating, sometimes frightening, sometimes reassuring, and that made our universe larger: Heinlein, Sturgeon, Asimov, Vance, Pangborn, Clarke, Anderson, among many others. Not by any means least among those names is Clifford D. Simak.

To one who grew up on science fiction (and I really did — the first book I ever bought all on my own was The Big Book of Science Fiction, edited by Groff Conklin; I think that was about fifth grade. It was by no means the first science fiction book I had ever read — this was in the days before school libraries were subject to the thought police.), there are names that echo through the memory, the writers who brought visions to life that were fascinating, sometimes frightening, sometimes reassuring, and that made our universe larger: Heinlein, Sturgeon, Asimov, Vance, Pangborn, Clarke, Anderson, among many others. Not by any means least among those names is Clifford D. Simak.

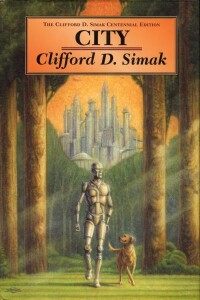

Old Earth Books has done us the signal service of reissuing two of Clifford Simak’s most memorable works in honor of the centennial of his birth in 1904, of which City is one. I confess that reading this book was an unsettling experience. It is, first off, one of the great “future histories” concocted by science fiction writers of the Golden Age. I remember vividly Poul Anderson’s version, and no less than Spider Robinson had reason to wax eloquent over Heinlein’s. Simak’s City is a series of connected stories, a series of legends, myths, and campfire stories told by Dogs about the end of human civilization, centering on the Webster family, who, among their other accomplishments, designed the ships that took Men to the stars and gave Dogs the gift of speech and robots to be their hands. (Perhaps one might take this as an early model for David Brin’s Uplift series.)

Simak says in his Author’s Foreword that City was written out of disillusion: “City,” the first story in the series, was published in 1944, in the closing years of the most destructive war in human history, and most of these stories come from the mid- and late 1940s. There is, however, as in so many stories of the period, a romantic vision underlying these tales, and I use the word “vision” advisedly. One of the hallmarks of the science fiction of the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s was its visionary quality, often reflected in utopian writing (or dystopian — it wasn’t all sugar and spice, although most of that came later, when the real world started catching up with us) and springing, I think, from its emphasis on the “hard” sciences, which at that point were wells of optimism: better living through technology and the race for space. We were dreamers, once.

These stories are slightly out of that mold, deeply melancholy, although the optimism is still there, way down inside. Humanity had screwed up, all our ideas of “progress” were wrong-headed and we couldn’t live up to our potential. So we just disappeared. We did, however, leave behind the Dogs, giving them speech and robots and high ideals. The stories are the Dogs’ legends of the long, slow dwindling of humanity.

I have to confess, as science the stories are a flop. The origin of the Dogs as a species with the capability of language relies on inheritance of acquired characteristics (a flat-out impossibility to those of us familiar with the mechanisms of evolution), and the exodus from the cities ignores humanity’s hard-wired instinct for sociality. After that point, the stories veer into what I can only call “science fantasy.” It doesn’t really matter.

Science fiction, like the world in general, has become much more sophisticated in its means in the last sixty years, thanks to such trailblazers as Roger Zelazny, J. G. Ballard, Samuel R. Delany and others who have forcefully (and sometimes forcibly) pulled science fiction and fantasy into alignment with the standards of style and structure found in “literary” mainstream fiction. By that measure, these stories are not that good, although I suspect that is deliberate (and Simak’s note on “Epilogue” bears me out). I fear that many readers, coming to them fresh and having little experience of the period, will dismiss them and thereby lose something very special. They are deceptive that way. There is something artless about them, something that almost seems like a beginning writer making all the mistakes, and then they gradually they pick up fluency and depth. And, of course, as one would expect of the very best science fiction, they are intensely human stories. The heroes are truly heroes, although they are not all human and there are no buckles being swashed. (I stoutly maintain that any artist makes certain decisions in the creation of his works, and we the audience must leave our preconceptions in the drawer and confront the work on the basis of what it actually is and how much sense those decisions make in their context.)

These stories are absorbing, and the visionary quality is something that contemporary writers in the field seem to have lost to a large extent, though not entirely. I think there are still a very few writers in the field who can match Simak, Anderson, Asimov, Silverberg, Farmer. Perhaps it was always just a few, and that’s why we remember them. Then again, it may just be part of the contemporary world: we did reach space. Then we turned around and came back home.

(Old Earth Books, 2004)