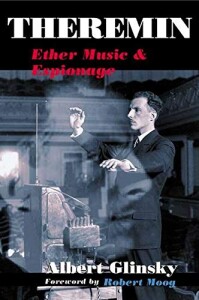

Ah, electronic music. Not much of it graces these electronic pages of Green Man Review. Now comes this bit of musiclore about one Leon Theremin, who may with justification be called the father of electronic music.

Ah, electronic music. Not much of it graces these electronic pages of Green Man Review. Now comes this bit of musiclore about one Leon Theremin, who may with justification be called the father of electronic music.

Most folks of my generation know the theremin from The Beach Boys’ 1969 hit, “Good Vibrations.” It’s the instrument that makes those swooping electronic howls during the chorus, sounding like a computerized operatic soprano with her finger slammed in a car door. A slightly earlier generation grew up associating the theremin with B-grade science fiction movies and screen or radio dramas about the darker side of the human psyche. It’s a strange instrument, to be sure.

Its inventor was a strange man, and the tale of his life is a microcosm of Russia during the 20th century, through revolution, purges, gulags, Cold War, perestroika and post-Soviet reconstruction. Albert Glinsky paints Theremin through his various rises and falls as something of an enigma, and also as a Russian Everyman: industrious, patiently stoic, patriotically naive, emotionally detached, and above all a survivor.

Lev Sergeyevich Termen, or Leon Theremin in the anglicized version of his name, was born in 1896 in St. Petersburg. From early in life he was fascinated by music, technology, science and engineering. He learned cello and piano as a child, and was at university studying engineering and physics during World War I and the Russian Revolution, when he was drafted by the Bolsheviks to work on radio and electronics technology. In his early 20s he entered the inner technocratic circles of the new Soviet Union, and discovered a way to create sounds through the interaction of radio waves and the human body.

Theremin perceived many uses for his discovery, particularly music and security. He initially called his invention the “radio watchman” and patented it as such. After he demonstrated it personally to Lenin, the Soviet leader urged him to use it as a propaganda tool in the drive for the electrification of Russia. He was issued a free pass to travel by rail anywhere in the Soviet Union, demonstrating his electric sound and light show; following Lenin’s death, the “watchman” was used to guard Soviet treasures, including Lenin’s tomb.

But his chief interest was in his “ether music” machine, which created music from radio static. In the late 1920s, he was sent on the road throughout the West to show off his invention as a demonstration of Soviet and Communist superiority in the arts and sciences. The Theremin machine was prophesied to be the death knell of the classical Western European musical heritage represented by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and their ilk.

Theremin saw his travels, which took him to Paris, then London and eventually to New York, as a way to proselytize for his musical ideas. But the Soviet authorities saw him as little more than another piece in a complex and far-reaching scheme to steal Western technology, business practices and government secrets and finance the rebuilding of Russia’s economy.

He spent nine years, 1929-38, in America promoting his music and security devices. After some initial success, a number of factors including the Depression brought his business ventures to failure, and he returned to Mother Russia. The rest of his life saw similar ups and downs, as he went from fame to obscurity and back, in prison camps and intelligence agencies and music academies.

Western musicians and technicians continued to experiment with and perfect Theremin’s ideas, and today music synthesizers can be heard in all kinds of music, from pop to jazz to opera.

Glinsky did an enormous amount of research for his book, and was even fortunate enough to meet Theremin before he died. His book, while slow going in some of the chapters about the inventor’s business failures in America, succeeds in portraying the life and times of this extraordinary genius of 20th century music and technology. I can’t say it any better than Robert Moog did in his Forward:

“At various times in his life, Theremin was a technological sensation, a political prisoner, a major contributor to the war effort of the Soviet Union, a beloved teacher, a forgotten hero, and an object of adulation by thousands of modern-day music technologists. This story of Theremin and his time will amaze you and probably, from time to time, overwhelm you. I’m sure you will enjoy reading it.”

(University of Illinois Press, 2000)